Blog & News

Spotlight on Health Behaviors: Adult Who Forgo Needed Medical Care and Adults Who Have No Personal Doctor

December 21, 2020:Prior to the arrival of the novel coronavirus, much of American consumer health care concerns surrounded rising costs of care. With health care spending rising a reported 4.6 percent in 2018 and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of the Actuary projecting an average annual increase of 5.4 percent for 2019 to hit a record $3.82 trillion or around $11,559 per person—this issue will remain at the forefront of concern for the foreseeable future.1

Compounding these trends in spending, the continued rise in the share of Americans without health insurance coverage has left more individuals without a means of protecting themselves or their families from the financial burden of illness or injury and without strong ties to health care providers and the health care system to access care.

The effects of rising health care spending and rising rates of uninsurance can be seen in direct measures of actual dollars, such as Medical Out-of-Pocket Spending and Percent of Individuals with High Medical Care Cost Burden, but also in more indirect avenues, such as changes in health behaviors and access to care.

Two measures of such behaviors, Adults Who Forgo Needed Medical Care and Adults with No Personal Doctor, are housed on SHADAC’s State Health Compare and have been recently updated with 2019 data from the Center for Disease Control's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). This blog provides an analysis of these indirect costs of rising health care spending and uninsurance in the year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and examines overall national and state-level trends as well as comparisons across race/ethnicity and educational attainment.

Adults Who Forgo Needed Care

Across the nation, progress was made in reducing the percentage of adults who forgo needed medical care in the years following the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). However, that progress began to flatten out by 2016 and has now begun to reverse course and display a trend of smaller but significant increases in recent years, such as the growth from 12.9% in 2018 to 13.4% in 2019 at the national level.

Trends by Education and Race/Ethnicity

Examining forgone care by individual breakdowns showed that disparities by education level and race/ethnicity, found in a previous SHADAC analysis, have persisted from the year before.

Across the U.S., adults with less than a high school degree saw their rates of forgone care hit 22.2% in 2019 from 21.1% in 2018;i a figure nearly triple the rate among adults with a bachelor’s degree, who saw their rate of forgone care rise to 7.9% in 2019 (up from 7.4% in 2018).

Nationally, Hispanic/Latino adults experienced the largest increase in rates of forgone care, rising to 21.4% in 2019 from 20.2% in 2018. African-American/Black and Hispanic/Latino adults were also significantly more likely to report going without needed medical care than White adults, with the former being 1.5 times more likely (15.7% vs. 10.9%) and the latter nearly twice as likely (21.4% vs. 10.9%).

State Trends

At the state level, the trends in forgone care are varied. Despite increasing national trends, some states, such as Florida and Michigan, have continued to make steady progress in reducing forgone care. Florida saw their overall rates drop by 5.9 percentage points,ii from 22.0% in 2011 to 16.0% in 2019, and Michigan saw a similarly steady drop in rates of forgone care from 16.5% in 2011 to 11.7% in 2019.

Unfortunately, progress in reducing the number of adults who report going without needed medical care has stalled in many states—California and Kentucky being two such examples. The former state has seen relatively unchanged rates of forgone care since 2016 (11.4%, 11.8% in 2017, and 11.9% in 2018 and 2019). The percentage of adults who have gone without needed medical care in Kentucky has likewise remained nearly unchanged from 2015 to 2019 (12.3% and 12.1%, respectively).

In other states, such as Kansas and Maine, rates of forgone care have followed the national trend and in 2015 begun reversing course on previous gains. The state of Kansas saw a 2.1 percentage-point increase from 2015 to 2019 (11.0% to 13.1%) and Maine saw a concerning increase of 2.9 percentage points during the same time period (9.4% in 2015 to 12.3% in 2019).

It is important to remember that these increases in forgone care occurred in the context of an economy that was growing steadily before the COVID recession. Though the release of 2020 data is at least another year away, early studies and surveys have given some indications as to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health behaviors. SHADAC conducted a survey in April 2020 in which over half of U.S. adults (51.1 percent) said they had delayed or canceled health care appointments due to the pandemic.2

Adults With No Personal Doctor

As with the measure of forgone medical care, more adults reported having a usual source of care after the passage of the ACA. However, once again this promising trend reversed itself in 2015, after which the percent of adults with no personal doctor or health care provider has increased each year, nearly reaching its pre-ACA peak in 2019 at 23.4% (23.8% in 2013). Both of these increasing trends have paralleled an increase in the rate of the uninsured across the nation, from 8.6% in 2016 to 9.2% in 2019.3

As with the measure of forgone medical care, more adults reported having a usual source of care after the passage of the ACA. However, once again this promising trend reversed itself in 2015, after which the percent of adults with no personal doctor or health care provider has increased each year, nearly reaching its pre-ACA peak in 2019 at 23.4% (23.8% in 2013). Both of these increasing trends have paralleled an increase in the rate of the uninsured across the nation, from 8.6% in 2016 to 9.2% in 2019.3

Trends by Education and Race/Ethnicity

Significant disparities by education level and race/ethnicity were again present for this measure in 2019.

At the national level, adults with less than a high school education were more than twice as likely as adults with a bachelor’s degree to report not having a regular doctor (34.7% versus 16.0%). This pattern was consistent across more than half of states, as adults with less than a high school degree were more than twice as likely to report having no doctor as those with a bachelor’s degree in 26 states, and more than three times as likely in 5 states (Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Nebraska, and New Hampshire). There was no statistical difference between these educational groups in D.C. and 6 states (Kentucky, Mississippi, North Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont and West Virginia).

At the national level, adults with less than a high school education were more than twice as likely as adults with a bachelor’s degree to report not having a regular doctor (34.7% versus 16.0%). This pattern was consistent across more than half of states, as adults with less than a high school degree were more than twice as likely to report having no doctor as those with a bachelor’s degree in 26 states, and more than three times as likely in 5 states (Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Nebraska, and New Hampshire). There was no statistical difference between these educational groups in D.C. and 6 states (Kentucky, Mississippi, North Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont and West Virginia).

Nationally, Hispanic/Latino and Black adults were both significantly more likely to report not having a regular doctor as compared to White adults. Hispanic/Latino adults were more than twice as likely as White adults to report not having a personal doctor (40.5% vs. 18.7%), and African-American/Black adults were more than 1.2 times as likely as White adults to report not having a personal doctor (22.7% vs. 18.7%). Again this pattern persisted among over half of the nation, as Hispanic/Latino adults were more than twice as likely to report not having a regular doctor as White adults in 28 states, and more than three times as likely to report the same in 3 states (Delaware, Maryland, and Nebraska). African-American/Black adults were at least 1.2 times as likely to report not having a regular doctor as White adults in 17 states, and this gap measured 1.5 times or larger in 6 states (Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Massachusetts, Michigan and Utah).

Nationally, Hispanic/Latino and Black adults were both significantly more likely to report not having a regular doctor as compared to White adults. Hispanic/Latino adults were more than twice as likely as White adults to report not having a personal doctor (40.5% vs. 18.7%), and African-American/Black adults were more than 1.2 times as likely as White adults to report not having a personal doctor (22.7% vs. 18.7%). Again this pattern persisted among over half of the nation, as Hispanic/Latino adults were more than twice as likely to report not having a regular doctor as White adults in 28 states, and more than three times as likely to report the same in 3 states (Delaware, Maryland, and Nebraska). African-American/Black adults were at least 1.2 times as likely to report not having a regular doctor as White adults in 17 states, and this gap measured 1.5 times or larger in 6 states (Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Massachusetts, Michigan and Utah).

Related Reading

Affordability and Access to Care in 2018: Examining Racial and Educational Inequities across the United States (Infographic)

Most U.S. Adults Report Reduced Access to Health Care due to Coronavirus Pandemic

Eleven Updated Measures are Now Available on State Health Compare

1 Hartman, M., Martin, A.B., Benson, J., & Catlin, A. (2019, December 5). National Health Care Spending in 2018: Growth Driven by Accelerations in Medicare and Private Insurance Spending. HealthAffairs, 39(1). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01451

Keehan, S.P., Cuckler, G.A., Poisal, J.A., Sisko, A.M., Smith, S.D., Madison, A.J., Rennie, K.E., Fiore, J.A., & Hardesty, J.C. (2020, March 24). National Health Expenditure Projections, 2019–28: Expected Rebound in Prices Drives Rising Spending Growth. HealthAffairs, 39(4). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00094

California Health Care Foundation (CHCF). (2019). Health Care Costs 101: Spending Keeps Growing. California Health Care Almanac. https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HealthCareCostsAlmanac2019.pdf

2 Planalp, C., Alarcon, G., & Blewett, L.A. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic caused more than 10 million U.S. adults to lose health insurance. https://shadac.org/news/SHADAC_COVID19_AmeriSpeak-Survey

3 State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC). (2020). 2019 ACS: Rising National Uninsured Rate Echoed Across 19 States; Virginia Only State to See Decrease (Infographics). https://www.shadac.org/sites/default/files/ACS_Estimates-2019-Infographic.pdf

Publication

SHADAC Article in Journal of Aging & Social Policy Urges States to Use COVID-19 Flexible Medicaid Authority for LTSS Eligibility

In response to the current public health emergency presented by COVID-19, especially the health risks pertaining to low-income older adults and disabled persons, states have been given new authority with regard to Medicaid in order to ease traditional complications and restrictions surrounding eligibility. A new article from SHADAC Director and UMN School of Public Health Professor Lynn A. Blewett, PhD, and SHADAC Research Fellow Robert Hest, MPP, focuses specifically on how this state-level Medicaid program flexibility, along with recent emergency waivers, can expand Medicaid financial eligibility for long-term supports and services (LTSS) for these at-risk individuals.

In response to the current public health emergency presented by COVID-19, especially the health risks pertaining to low-income older adults and disabled persons, states have been given new authority with regard to Medicaid in order to ease traditional complications and restrictions surrounding eligibility. A new article from SHADAC Director and UMN School of Public Health Professor Lynn A. Blewett, PhD, and SHADAC Research Fellow Robert Hest, MPP, focuses specifically on how this state-level Medicaid program flexibility, along with recent emergency waivers, can expand Medicaid financial eligibility for long-term supports and services (LTSS) for these at-risk individuals.

Traditionally, Medicaid LTSS eligibility criteria for states (though federal standards are also a key component) have been based on financial rules and functional needs assessments. Due to complexities surrounding these eligibility requirements, many beneficiaries are at risk of losing coverage throughout the year. Under public health emergency authority granted to states during the COVID-19 pandemic, however, mechanisms such as state plan amendments (SPAs), section 1115 and 1135 waivers, and 1915(c) Appendix K can be used by states to ease these difficulties and ensure that eligible individuals get coverage, including:

- Reducing administrative burdens for applicants

- Streamlining eligibility redeterminations

- Extending deadlines to conduct evaluations/assessments

- Temporarily suspending authorization requirements

- Relaxing eligibility requirements

While states are adopting these flexible measures to expand eligibility, they are simultaneously facing increasing pressures to curb state spending as budgets are constrained during the pandemic. Medicaid spending, most especially for LTSS, is a prime target for cuts as it accounts for a large majority of states’ budgets. However, the article argues that LTSS provided by Medicaid is an essential service for low-income older adults and disabled individuals who are at particular risk from COVID-19, and therefore it is critical that eligibility and flexibility be maintained in order to meet the increasing demand for services created by the coronavirus.

Read the full article in the Journal of Aging & Social Policy.

Blog & News

Most U.S. Adults Report Reduced Access to Health Care due to Coronavirus Pandemic

April 29, 2020:More than half worried about their ability to pay for COVID-19 health care

Colin Planalp, MPA, Kathleen Thiede Call, PhD, Giovann Alarcon, MPP, Lynn A. Blewett, PhD

According to results from a new April 2020 survey, a majority of adults in the United States say that their access to health care services has been negatively affected by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, with the crisis causing delayed or canceled health care appointments. Over half of adult respondents also reported being “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about their ability to afford health care if they contract COVID-19. These findings come from a recent nationally representative survey of U.S. adults conducted between April 8 and 13, 2020, by survey firm SSRS and the State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC).

Worries about affordability of care for COVID-19

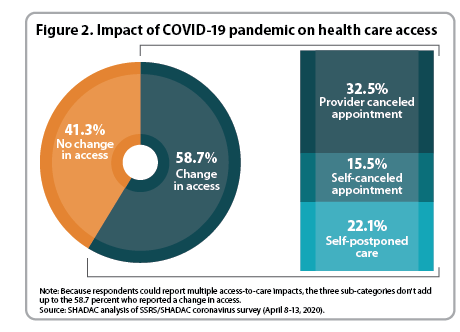

The survey asked respondents how worried they were about being able to afford health care if they contracted COVID-19. Responses revealed that 54.5 percent of U.S. adults were “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about their ability to afford health care if they were to contract the coronavirus (Figure 1). However, that rate varied substantially across different segments of the population.

Nearly three-quarters (72.6 percent) of U.S. adults age 18-29 reported being “very” or “somewhat worried” about their ability to afford care should they contract COVID-19, and almost two-thirds (63.5 percent) of persons of color (e.g., American Indian, Asian and Pacific Islander, Black and Hispanic) also reported being “very” or “somewhat worried.” Both of those rates were significantly higher than the overall rate of 54.5 percent.

Higher rates of worry about COVID-19-related health care affordability may be influenced in part by higher rates of uninsurance. The SSRS/SHADAC survey also confirmed evidence of persistent disparities in health insurance coverage, finding that uninsurance rates were significantly higher among adults age 18-29 (18.2 percent) and persons of color (14.7 percent) as compared to the overall adult population (9.2 percent) at the onset of the crisis.

One particular concern during the pandemic is that those who are uninsured and those who are worried about the cost of health care may either avoid or delay seeking health care for COVID-19—potentially putting them at greater risk of severe illness or death, and leading them to inadvertently expose others in the community to the virus. Given these risks, the disparity in uninsured rates for persons of color is especially troubling in light of research by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) finding that Black populations in the U.S. have higher rates of hospitalization due to COVID-19.1

Reduced health care access caused by pandemic

While the American health care system has prepared for and, in some states, already experienced waves of patients suffering from COVID-19, the U.S. population has other continuing health care needs, including regular preventive care, treatment of chronic conditions, and medical emergencies, such as heart attacks and strokes.

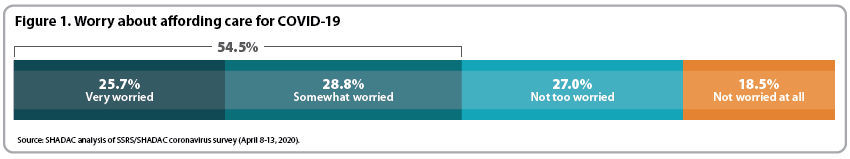

Anticipation of the coronavirus surge, however, has caused some health care providers to cancel appointments for conditions other than COVID-19, and it has driven some individuals to cancel or delay care due to concerns of exposure to the virus.

The survey found that 58.7 percent of U.S. adults reported the pandemic hindering their access to health care services, by way of either personal decisions to postpone making an appointment or canceling or postponing existing appointments, or having an appointment canceled by a health care provider (Figure 2). Almost one-third (32.5 percent) said they had a medical or dental appointment canceled by their provider due to the pandemic. Roughly one-fifth (22.1 percent) said they postponed scheduling a health care appointment due to concerns about exposure to the coronavirus, and 15.5 percent said they canceled an already scheduled appointment due to exposure concerns, as well.

Crisis caused loss of health insurance

In addition to the 9.2 percent of U.S. adults who were uninsured at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, another 2.6 percent reported losing health insurance coverage since the pandemic began, either because they lost health insurance through an employer or they canceled their coverage to pay for other expenses.

That rate of 2.6 percent equates to roughly 6.5 million U.S. adults who reported losing their health insurance since the pandemic began. However, there are several factors that demonstrate that those figures are an underestimate of the number of people who have lost health insurance. First, this survey was conducted between April 8 and 13, 2020, but millions more Americans have filed new weekly unemployment claims since the survey ended, and it’s likely that many of those individuals also lost their employer-based insurance coverage when they became unemployed.2

Second, the rates from the survey are only based on the respondent’s own insurance status, not on whether other family members or dependents, such as spouses and children, also lost coverage. Another recent study by the University of Minnesota, including researchers from SHADAC, found that as many as 18.4 million Americans may be at risk of losing employer-sponsored insurance due to the coronavirus crisis.3 If uninsured rates continue to climb during the crisis, it is possible that worries about affording care for COVID-19 and impacts on health care access may become even more prevalent.

More on the survey

The Coronavirus Poll was funded and conducted by SSRS. SSRS is a public opinion and survey research company based in Media PA. Data collection was conducted using SSRS Opinion Panel, a nationally representative probability-based web panel (https://ssrs.com/opinion-panel/). Surveys were conducted online from April 8-13, 2020, among a nationally representative sample of 1,001 respondents age 18 and older. The margin of error for total respondents is +/-4.4 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.

Acknowledgment: We appreciate contributions to the survey by Sarah Hagge and Alisha Baines Simon of the Health Economics Program at the Minnesota Department of Health.

1 Garg, S., Kim, L., Whitaker, M., O’Halloran, A., Cummings, C., Holstein, R, et al. (2020, April 17). Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-Net, 14 states, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Weekly, 69(15), 458-464. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3

2 U.S. Department of Labor. (2020, April 23). COVID-19 Impact: The COVID-19 virus continues to impact the number of initial claims and insured unemployment. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OPA/newsreleases/ui-claims/20200691.pdf

3 Golberstein, E., Abraham, J.M., Blewett, L.A., Fried, B., Hest, R., & Lukanen, E. (2020). Estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on disruptions and potential loss of employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI). Retrieved from https://www.shadac.org/sites/default/files/publications/UMN%20COVID-19%20ESI%20loss%20Brief_April%202020.pdf

Publication

2018 State-level Estimates of Medical Out-of-Pocket Spending for Individuals with Employer-sponsored Insurance Coverage

U.S. health care spending continues to grow, reaching $3.6 trillion and 17.7% of the GDP in 2018.[i] Unfortunately, a significant share of these costs are increasingly born by Americans in the form of increased deductibles, copayment, and coinsurance—commonly referred to as patient “out-of-pocket” (OOP) costs. Even for the 52% of Americans who have private health insurance through their own or their spouse’s employer, affordability of health care is a pressing issue. Nationally, the average deductible for families in 2018 was $3,392, and almost half (49.1%) of all Americans were enrolled in high-deductible health plans with a deductible of at least $2,700 for family coverage.[ii],[iii]

U.S. health care spending continues to grow, reaching $3.6 trillion and 17.7% of the GDP in 2018.[i] Unfortunately, a significant share of these costs are increasingly born by Americans in the form of increased deductibles, copayment, and coinsurance—commonly referred to as patient “out-of-pocket” (OOP) costs. Even for the 52% of Americans who have private health insurance through their own or their spouse’s employer, affordability of health care is a pressing issue. Nationally, the average deductible for families in 2018 was $3,392, and almost half (49.1%) of all Americans were enrolled in high-deductible health plans with a deductible of at least $2,700 for family coverage.[ii],[iii]

The State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) at the University of Minnesota continues to monitor trends in coverage, access, and affordability. This brief highlights the affordability of coverage for those with employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI). Using data from the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the 2019 Current Population Survey (CPS; data year 2018), we estimated family out-of-pocket costs for people with employer coverage across all 50 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.). For individuals with ESI, we looked at: (1) the family median out-of-pocket costs by state, and (2) an estimate of the high medical cost burden where family out-of-pocket spending is greater than 10% of household income. For additional estimates, please visit SHADAC’s State Health Compare web tool.

[i] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). (2019, December 5). NHE Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet/

[ii] State Health Access Data Assistance Center analysis of the 2018 American Community Survey microdata.

[iii] State Health Access Data Assistance Center, State-level Trends in Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance, 2014-2018. Available at: https://www.shadac.org/ESIReport2019

Blog & News

Affordability and Access to Care in 2018: Examining Racial and Educational Inequities across the United States (Infographic)

December 17, 2019: The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently reported that the cost of health care spending in the United States increased by 4.6 percent last year to reach an all-time high of approximately $3.6 trillion.1 This report comes amidst a number of other concerning health care cost-related trends, such as the largest single-year increase for single-coverage premiums in 2018 from $6,368 to $6,715 (5.4 percent) for workers enrolled in employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) and an increase in average household spending on health care (out of pocket expenses, cost-sharing for ESI, and payroll taxes for Medicare, etc.) rising to a record $1.04 trillion.2

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently reported that the cost of health care spending in the United States increased by 4.6 percent last year to reach an all-time high of approximately $3.6 trillion.1 This report comes amidst a number of other concerning health care cost-related trends, such as the largest single-year increase for single-coverage premiums in 2018 from $6,368 to $6,715 (5.4 percent) for workers enrolled in employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) and an increase in average household spending on health care (out of pocket expenses, cost-sharing for ESI, and payroll taxes for Medicare, etc.) rising to a record $1.04 trillion.2

Rising expenses such as these have contributed to the record number of Americans (25 percent) who reported in 2019 that either themselves or a family member skipped or delayed needed medical care due to cost, according to the results from a new Gallup poll released earlier this month.3

This post examines Americans’ access and ability to afford medical care, focusing on inequities related to race/ethnicity and education, and using two recently updated measures from SHADAC’s State Health Compare: Adults Who Forgo Needed Medical Care and Adults with No Personal Doctor. These measures come from a SHADAC analysis of 2018 data from the CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).

Racial and educational inequities persist in adults’ reported ability to afford needed medical care

Significant inequities in adults’ ability to afford medical care by race/ethnicity emerged when we examined the updated data for 2018. At the national level, our analysis showed that Hispanic/Latino adults were nearly twice as likely as White adults to forgo needed medical care due to cost (20.2 percent versus 10.5 percent), and African Americans/Black adults were 1.5 times as likely to report forgoing care compared to White adults (16.0 percent versus 10.5 percent). Hispanic/Latino adults were also significantly more likely to report forgoing medical care than White adults in 35 states and D.C., and this gap was greater than 20 percentage points in Maryland (31.4 percent versus 7.4 percent) and Missouri (34.4 percent versus 11.1 percent). Black adults were significantly more likely to report going without care than White adults in 24 states and D.C., and this gap was greater than 10 percentage points in four states: Iowa (16.2 percentage points), North Dakota (15.5 percentage points), Utah (11.5 percentage points), and Minnesota (10.2 percentage points).

Significant inequities in adults’ ability to afford medical care by race/ethnicity emerged when we examined the updated data for 2018. At the national level, our analysis showed that Hispanic/Latino adults were nearly twice as likely as White adults to forgo needed medical care due to cost (20.2 percent versus 10.5 percent), and African Americans/Black adults were 1.5 times as likely to report forgoing care compared to White adults (16.0 percent versus 10.5 percent). Hispanic/Latino adults were also significantly more likely to report forgoing medical care than White adults in 35 states and D.C., and this gap was greater than 20 percentage points in Maryland (31.4 percent versus 7.4 percent) and Missouri (34.4 percent versus 11.1 percent). Black adults were significantly more likely to report going without care than White adults in 24 states and D.C., and this gap was greater than 10 percentage points in four states: Iowa (16.2 percentage points), North Dakota (15.5 percentage points), Utah (11.5 percentage points), and Minnesota (10.2 percentage points).

Nationwide, Americans with less than a high school degree were almost three times as likely to report going without needed medical care due to cost as compared to those with a bachelor’s degree (21.1 percent versus 7.4 percent) in 2018. Adults with less than a high school education were significantly more likely to report forgone care due to cost compared to adults with college degrees in 2018 in all but two states—Montana and Vermont—and in the District of Columbia (D.C.). For four states this gap was greater than 20 percentage points in 2018—Georgia (21.1 percentage points), Maryland (20.9 percentage points), Oklahoma (21.2 percentage points), and Virginia (21.2 percentage points).*

Racial/ethnic minorities and adults without a high school diploma less likely to have a personal doctor

Nationally, Hispanic/Latino and Black adults were both significantly more likely to report not having a regular doctor as compared to their White counterparts. Our analysis revealed that Hispanic/Latino adults were more than twice as likely as White adults to report not having a personal doctor (38.8 percent versus 18.4 percent), and Black adults were nearly 25 percent more likely to report not having a personal doctor compared with White adults (22.8 percent versus 18.4 percent).*

Nationally, Hispanic/Latino and Black adults were both significantly more likely to report not having a regular doctor as compared to their White counterparts. Our analysis revealed that Hispanic/Latino adults were more than twice as likely as White adults to report not having a personal doctor (38.8 percent versus 18.4 percent), and Black adults were nearly 25 percent more likely to report not having a personal doctor compared with White adults (22.8 percent versus 18.4 percent).*

These inequities in access to care by race/ethnicity were present in a large majority of states. A significant gap between Hispanic/Latino and White adults with no personal doctor was present in 43 states, and Hispanic adults were more than three times as likely to report not having a personal doctor in five states (Connecticut, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, and North Carolina). This significant gap also persisted between Black and White adults in 20 states, as we found that Black adults were more than twice as likely to not have a personal doctor in three states—Connecticut (22.8 percent versus 10.8 percent), Iowa (31.2 percent versus 15.1 percent), and Rhode Island (21.2 percent versus 9.9 percent).*

Nationally, adults with less than a high school degree were more than twice as likely to not have a regular doctor as those with an undergraduate degree or greater (32.4 percent versus 15.7 percent). This pattern was consistent across nearly the entire nation, as adults with less than a high school education were significantly more likely than college graduates to report not having a personal doctor in 46 states. The gap between less than high school graduates and college graduates was larger than 20 percentage points in eight states (California, Colorado, Georgia, Maryland, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, and Utah).

Note

* Data were not available or were suppressed for some states because the number of sample cases was too small, so this number could be higher if data were available in all states. For education breakdowns, adults are defined as 25 years of age and above. For race/ethnicity breakdowns, adults are defined as 18 years of age and above. All differences are statistically significant at the 95% level.

Explore Additional BRFSS Data at State Health Compare

Visit State Health Compare to explore national and state-level estimates for the following measures that also come from the BRFSS:

Income Inequality

Sales of Opioid Painkillers

Adult Cancer Screenings

Chronic Disease Prevalence

Activities Limited due to Health Difficulty

Adult Obesity

Adult Binge Drinking

Adult Smoking

Adult E-Cigarette Use (New Measure)

State Health Compare also features a number of other indicator categories, including: health insurance coverage, cost of care, access to and utilization of care, care quality, health behaviors, health outcomes, and social determinants of health.

Related Reading

Now Available on State Health Compare: Eleven Updated Measures and One Brand New Measure

Educational Attainment and Access to Health Care: 50-State Analysis

Fifty-State Analysis Finds Lower Access to Care among Adults with Less Education

[1] Hartman, M., Martin, A.B., Benson, J., & Catlin, A. (2019, December 5). National Health Care Spending in 2018: Growth Driven by Accelerations in Medicare and Private Insurance Spending. HealthAffairs. [E-published ahead of print.] https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01451

[2] State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC). (2019, August 14). State-level Trends in Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance, 2014-2018. Retrieved from https://www.shadac.org/ESIReport2019

Murad, Y. (2019, December 5). U.S Health Spending Rose to $3.6 Trillion in 2018, Propelled by Health Insurance Tax. Morning Consult. Retrieved from https://morningconsult.com/2019/12/05/u-s-health-spending-rose-to-3-6-trillion-in-2018-propelled-by-health-insurance-tax/

[3] Saad, L. (2019, December 9, 2019). More Americans Delaying Medical Treatment Due to Cost. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/269138/americans-delaying-medical-treatment-due-cost.aspx