Blog & News

Examining Discrimination and Health Care Access by Sexual Orientation in Minnesota

March 22, 2023:Authors: Natalie Mac Arthur, Jeremy Duval, Kathleen Call

|

More than one-third of lesbian/gay adults in Minnesota reported experiencing discrimination from health care providers based on their sexual orientation and gender identity. |

Survey Question OverviewIn this analysis, we examined the experiences of adults in Minnesota by sexual orientation using data from the biennial 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA). The MNHA asked respondents how often their gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression cause health care providers to treat them unfairly. In addition to this measure of SOGI-based discrimination, this survey includes information on access to health care such as forgone care due to costs. |

Introduction

Discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) from health care providers is a barrier to creating an equitable health care system. Nearly one in five lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LBGTQ) adults reports avoiding health care due to anticipated discrimination (Casey et al., 2019). Compared with straight adults, lesbian/gay and bisexual adults are more likely to forgo or delay health care (Jackson et al., 2016, Nguyen et al., 2018). However, less is known about the association between reports of SOGI-based discrimination from health care providers and health care access.

We included three sexual orientation categories in this study: straight, lesbian/gay, and bisexual/pansexual. Survey respondents also had the option to select “none of these” and write in their own response. Due to sample size limitations, we excluded observations with responses that we could not recode to the existing categories. We tabulated SOGI-based discrimination and four measures of health care access by sexual orientation for adults in Minnesota. We also examined differences in health care access for respondents who did and did not report discrimination.

Results

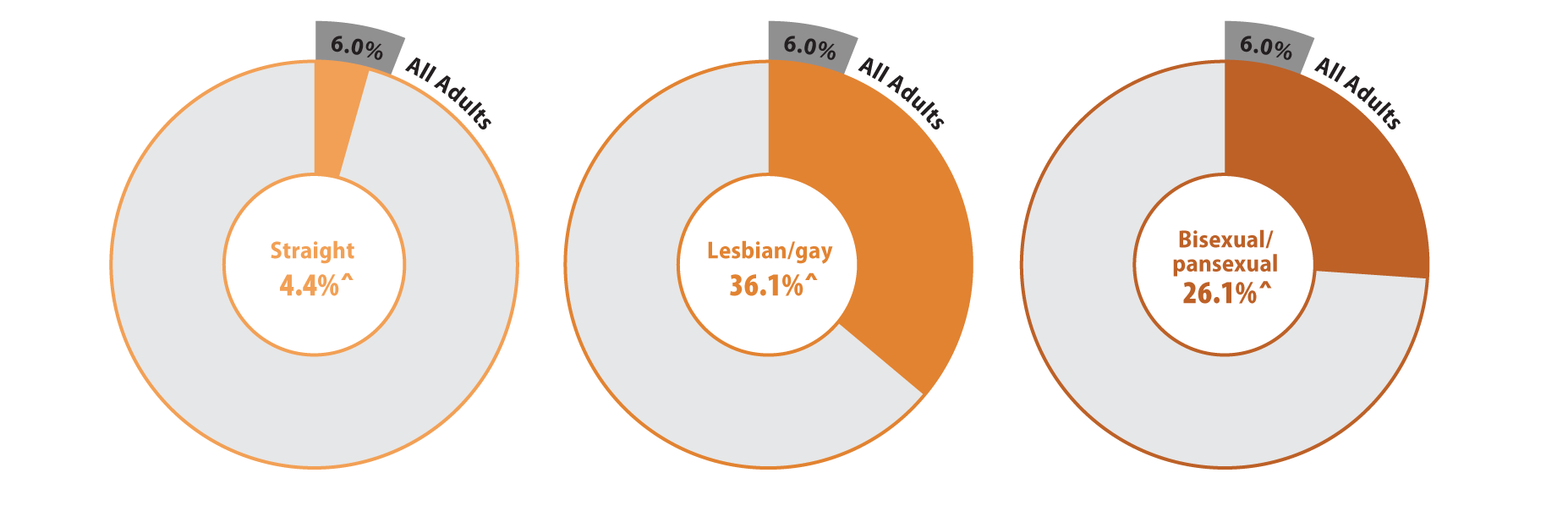

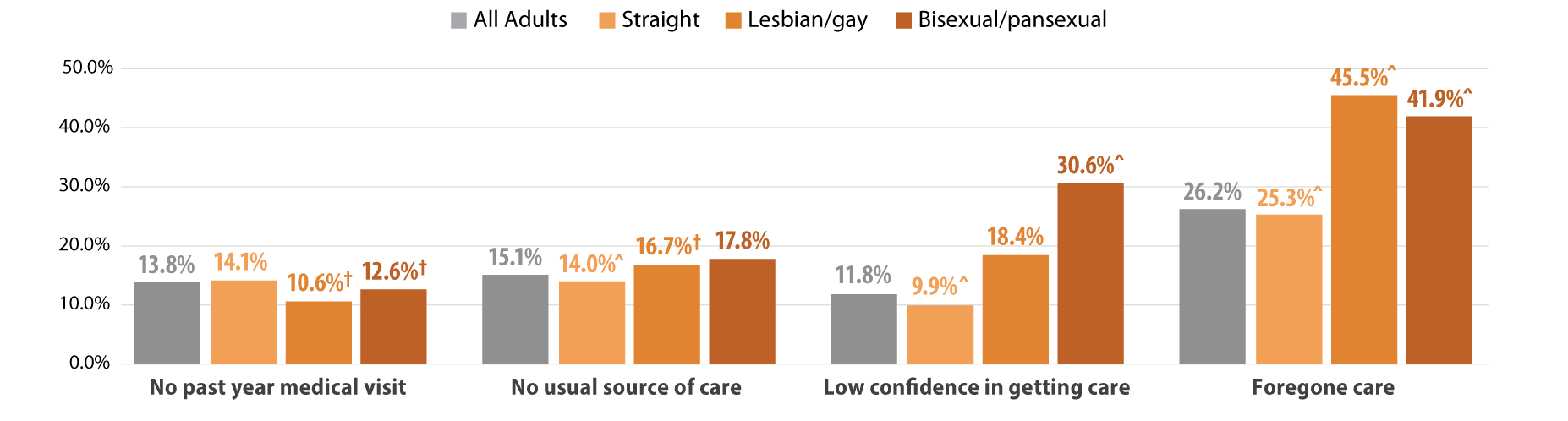

Reports of discrimination from health care providers based on SOGI were significantly higher among lesbian/gay (36.1%) and bisexual/pansexual (26.1%) populations compared with the state average of 6% (Figure 1). Sexual minorities were also more likely to report barriers to health care access when compared with all adults in Minnesota (Figure 2). Low confidence in getting needed health care was significantly above the state average (11.8%) for people who identify as bisexual/pansexual (30.6%). Statewide, over a quarter of adults reported forgone care due to costs (26.2%), which included routine medical care, prescription drugs, dental care, specialists, and mental health care. Rates of forgone care were significantly higher for people who identify as lesbian/gay (45.5%) or bisexual/pansexual (41.9%).

Figure 1. Unfair treatment from health care providers based on gender or sexual orientation in Minnesota

^ Rate significantly different from All Adults at the 95% confidence level.

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

Figure 2. Health care access and barriers to care

^ Rate significantly different from All Adults at the 95% confidence level.

† Estimate may be unreliable due to limited data (relative standard error greater than or equal to 30%).

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

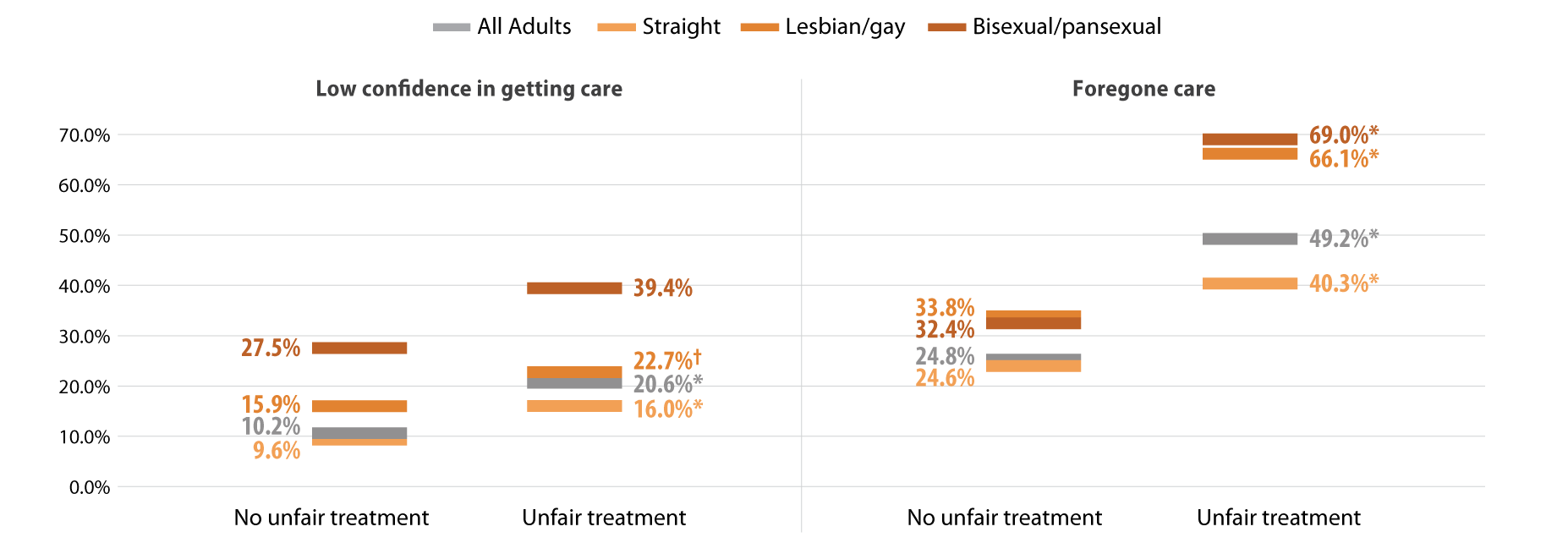

We found that Minnesotans who experienced SOGI-based discrimination were more likely to have low confidence in getting care and forgone care compared to those who did not experience discrimination (Figure 3). People who experienced discrimination had elevated barriers across all population groups including people identifying as straight, lesbian/gay, or bisexual/pansexual. However, low confidence in care was highest among bisexual/pansexual adults who reported SOGI-based discrimination (39.4%). Half of all adults with SOGI-based discrimination reported forgone care due to costs, while about two-thirds of bisexual/pansexual (69.0%) and lesbian/gay (66.1%) adults who reported SOGI-based discrimination had forgone care.

Figure 3. Experiences of gender-based discrimination associated with barriers to health care access

* Significant difference within a given subpopulation between rates of people who experienced unfair treatment and those who did not.

† Estimate may be unreliable due to limited data (relative standard error greater than or equal to 30%).

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

Discussion

MethodsData are from the 2021 Minnesota Health Access (MNHA) survey, which is a biennial population-based survey on health insurance coverage and access conducted in collaboration with the Minnesota Department of Health. We limited the analysis to adults responding for themselves about experiences of discrimination and access (n=10,003); we excluded proxy reports (e.g., a household member answering for a spouse or roommate). Tests for statistical significance were conducted at the 95% confidence level. |

Within the health care setting, discrimination based on SOGI was prevalent among lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual adults. SOGI-based discrimination from health care providers was reported by over a third of lesbian/gay adults in Minnesota and over a quarter of bisexual/pansexual adults. Barriers to health care access, including low confidence in getting care and forgone care, were also high among lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual adults compared with the average rates seen among adults in Minnesota. Further, reports of SOGI-based discrimination correlated with even higher rates of barriers to access among lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual adults; a majority of these populations who reported discrimination also had forgone health care due to costs.

Discrimination by health care providers has substantial clinical implications. Across populations, discrimination negatively affects mental and physical health (Pascoe and Richman, 2009). Compared with straight adults, lesbian/gay and bisexual adults experience health disparities including mental and physical health, activity limitations, and chronic conditions (Gonzales and Henning-Smith, 2017). For LBGTQ adults, both discrimination and barriers to health care are associated with worse mental health, behavioral health, and health-related quality of life (Lee 2016 et al., Jung et al., 2023). One recent study suggests that delayed health care partially mediates the connection between discrimination and worse health status among LBGTQ women (Scott et al., 2022). Our work contributes evidence linking provider discrimination to forgone health care and lack of confidence in getting care.

The clinical impact of discrimination is likely to vary across the life course and across the spectrum of intersectional identities including LBGTQ and race/ethnicity. Compared with lesbians, bisexual women are more likely to report poor physical and mental health and disabilities; both groups of women face higher risks than straight women (Fredriksen-Goldsen 2023). Gay Black and Hispanic men face greater barriers to health care access than gay white men (Hsieh et al., 2017). Among older adults, one survey found that nearly four out of five LBGTQ people anticipate encountering discrimination in long-term care services (Dickson et al., 2022).

Differences in health care access and socioeconomic resources may exacerbate the influence of provider discrimination on health outcomes. Although studies have found that delays in health care among lesbian/gay and bisexual adults persist even with insurance coverage, their coverage may not provide comparable affordability of health care relative to straight adults (Jackson et al., 2016, Nguyen et al., 2018,Tabaac et al., 2020). Lesbian/gay and bisexual adults are less likely to have private coverage and more likely to have purchased a plan from the individual market, which may have higher premiums and deductibles. Furthermore, they are also more likely to experience lapses in coverage. These studies indicate that both cost concerns and previous bad health care experiences contribute to delays in care. Our results add to the growing body of literature documenting high rates of forgone care due to cost for lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual adults. Additionally, we document lack of confidence in getting health care among these populations and greater barriers to access among those who reported SOGI-based discrimination from a health care provider.

Conclusion

Reports of discrimination among lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual Minnesotans are troubling and require a response. The Affordable Care Act, which expanded Medicaid in willing states, also expanded non-discrimination protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity (KFF, 2014). However, these protections are limited in promoting health care access. Relative to other states, Minnesota offers a robust Medicaid program. Barriers to access may be even higher for LBGTQ people in states that did not expand Medicaid and states with fewer protective non-discrimination laws. Socioeconomic policies at the federal and state level are important for addressing gaps in health equity for many members of the LBGTQ community.

Greater availability of data including SOGI measures would strengthen efforts to better understand and address the health care needs of LBGTQ populations (SHADAC, 2021). Direct measures of discrimination are also important to monitor progress in providing equitable access to health care services (Lett et al., 2022). Ongoing research is needed to improve health equity and address barriers to health care for LBGTQ populations.

Check out our companion blog "Examining Gender-Based Discrimination in Health Care Access by Gender Identity in Minnesota".

References

Casey, L. S., Reisner, S. L., Findling, M. G., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health services research, 54 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 1454–1466. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13229

Dickson, L., Bunting, S., Nanna, A., Taylor, M., Spencer, M., & Hein, L. (2022). Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Adults’ experiences with discrimination and impacts on expectations for long-term care: Results of a survey in the southern United States. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(3), 650-660.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Romanelli, M., Jung, H. H., & Kim, H. J. (2022). Health, economic, and social disparities among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Sexually Diverse Adults: Results from a population-based study. Behavioral Medicine, 1-12.

Gonzales, G., & Henning-Smith, C. (2017). Health disparities by sexual orientation: results and implications from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Journal of Community Health, 42, 1163-1172.

Jackson, C. L., Agénor, M., Johnson, D. A., Austin, S. B., & Kawachi, I. (2016). Sexual orientation identity disparities in health behaviors, outcomes, and services use among men and women in the United States: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 807. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3467-1

Kates, J., & Ranji, U. (2014, February 21). Health Care Access and Coverage for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community in the United States: Opportunities and Challenges in a New Era. KFF. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/perspective/health-care-access-and-coverage-for-the-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-lgbt-community-in-the-united-states-opportunities-and-challenges-in-a-new-era/

Lett E., Asabor E., Beltrán S., Cannon A.M., Arah O.A. (2022). Conceptualizing, Contextualizing, and Operationalizing Race in Quantitative Health Sciences Research. Ann Fam Med 20(2):157-163. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2792

Nguyen, K. H., Trivedi, A. N., & Shireman, T. I. (2018). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults report continued problems affording care despite coverage gains. Health Affairs, 37(8), 1306-1312.

Pascoe, E. A., & Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 135(4), 531.

Scott, S. B., Knopp, K., Yang, J. P., Do, Q. A., & Gaska, K. A. (2022). Sexual minority women, health care discrimination, and poor health outcomes: A mediation model through delayed care. LGBT Health. http://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2021.0414

SHADAC. (2021, October). A New Brief Examines the Collection of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) Data at the Federal Level and in Medicaid. https://www.shadac.org/news/new-brief-examines-collection-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-sogi-data-federal-level

Tabaac, A. R., Solazzo, A. L., Gordon, A. R., Austin, S. B., Guss, C., & Charlton, B. M. (2020). Sexual orientation-related disparities in health care access in three cohorts of US adults. Preventive Medicine, 132, 105999.

Blog & News

Race/Ethnicity Data in CMS Medicaid (T-MSIS) Analytic Files: 2020 Data Assessment

Updated January 2023:The Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) is the largest national database of current Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) beneficiary information collected from U.S. states, territories, and the District of Columbia (DC).1 T-MSIS data are critical for monitoring and evaluating the utilization of Medicaid and CHIP, which together provide health insurance coverage to more than 90 million people.2

T-MSIS data files are challenging to use directly for research and analytic purposes due to their size and complexity. To optimize these files for health services research, CMS repackages them into a user-friendly, research-ready format called T-MSIS Analytic Files (TAF) Research Identifiable Files (RIF). One such file, the Annual Demographic and Eligibility (DE) file, contains race and ethnicity information for Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries. This information is vital for assessing enrollment, access to services, and quality of care across racial and ethnic subgroups in the Medicaid/CHIP population, whose members are particularly vulnerable due to limited income, physical and cognitive disabilities, old age, complex medical conditions, housing insecurity, and other social, economic, behavioral, and health needs.

Completeness of race and ethnicity data reported to CMS remains inconsistent among the states, territories, and DC. To guide researchers and other consumers in their use of T-MSIS data, CMS produces data quality assessments of the race and ethnicity data along with other data such as enrollment, claims, expenditures, and service use. The Data Quality (DQ) assessments for race and ethnicity data have been posted for data years 2014 through 2020 and indicate varying levels of “concern” regarding race and ethnicity data completeness. Some data years have multiple data versions (e.g., Preliminary, Release 1, Release 2), each with its own DQ assessment. This blog explores 2020 Data Release 1, the most recent T-MSIS race and ethnicity data for which a DQ assessment is available.

Evaluation of T-MSIS Race and Ethnicity Data

DQ assessments for each year and release of T-MSIS data are housed in the Data Quality Atlas (DQ Atlas), an online evaluation tool developed as a companion to T-MSIS data.3 The DQ Atlas assesses T-MSIS race and ethnicity data using two criteria: the percentage of beneficiaries with missing race and/or ethnicity values in the TAF; and the number of race/ethnicity categories (out of five) that differ by more than ten percentage points between the TAF and American Community Survey (ACS) data. Taken together, these two criteria indicate the level of “concern” (i.e., reliability) for states’ T-MSIS race/ethnicity data. Five “concern” categories appear in the DQ Atlas: Low Concern, Medium Concern, High Concern, Unusable, and Unclassified. States with substantial missing race/ethnicity data or race/ethnicity data that are inconsistent with the ACS – a premier source of demographic data – are grouped into either the High Concern or Unusable categories, whereas states with relatively complete race/ethnicity data or race/ethnicity data that align with ACS estimates are grouped into either the Low Concern or Medium Concern categories. The Unclassified category includes states for which benchmark data are incomplete or unavailable for a given data year and version.

To construct the external ACS benchmark for evaluating T-MSIS data, creators of the DQ Atlas combine race and ethnicity categories in the ACS to mirror race and ethnicity categories reported in the TAF (see Table 1). More information about the evaluation of T-MSIS race and ethnicity data is available in the DQ Atlas’ Background and Methods Resource.

Table 1. Crosswalk of Race and Ethnicity Variables between the TAF and ACS

| Race/Ethnicity Category |

Race/Ethnicity Flag Value in TAF |

Combination of Race and Hispanic Variables in ACS |

| Hispanic, all races |

7=Hispanic, all races | Hispanic, all races |

| Other races, non-Hispanic |

4= American Indian and Alaska Native, non-Hispanic 5=Hawaiian/Pacific Islander 6=Multiracial, non-Hispanic |

- American Indian alone - Alaska Native alone - American Indian and Alaska Native tribes specified; or American Indian or Alaska native, non-specified and no other race - Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander alone - Some other race alone - Two or more races |

Source: Medicaid.gov. (n.d.). DQ Atlas: Background and methods resource [PDF file]. Available from https://www.medicaid.gov/dq-atlas/downloads/background_and_methods/TAF_DQ_Race_Ethnicity.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2023.

Quality Assessment by State

Table 2 shows the Race and Ethnicity DQ Assessments for the 2020 TAF (Data Version: Release 1). Approximately the same number of states received a rating of Low Concern (15 states), Medium Concern (17 states, including PR), and High Concern (16 states, including DC). Four states (Alabama, Kansas, Rhode Island, and Tennessee) received an “Unusable” rating, as each of these states was missing at least 50 percent of race/ethnicity data. Most of the Medium Concern states (14 of 17) fell into the subcategory denoting the higher percentage range of missing race/ethnicity data (from 10 percent up to 20 percent). A similar pattern can be seen among the High Concern states, most of which (15 of 16) fell into the subcategory denoting the highest percentage range of missing race/ethnicity data (from 20 percent up to 50 percent). The categorization criteria used to determine the levels of concern for the 2020 TAF Release 1 data are the same as those used to assess T-MSIS data from previous years and versions.

Table 2. Race and Ethnicity Data Quality Assessment, 2020 T-MSIS Analytic File (TAF) Data Release 1

| Data quality assessment |

Percent of beneficiaries with missing race/ethnicity values | Number of race/ethnicity categories where TAF differs from ACS by more than 10% |

Number of states* |

States |

| Low Concern | <10% | 0 | 15 | AK, CA, DE, MI, NE, NV, NM, NC, ND, OH, OK, PA, SD, VA, WA |

| Medium Concern | <10% | 1 or 2 | 3 | GA, ID, IL |

| 10% - <20% | 0 or 1 | 14 | FL, IN, KY, ME, MN, MS, MT, NH, NJ, PR, TX, VT, WV, WI | |

| High Concern | <10% | 3 or more | 0 | - |

| 10% - <20% | 2 or more | 1 | LA | |

| 20% - <50% | Any value | 15 | AZ, AR, CO, CT, DC, HI, IA, MD, MA, MO, NY, OR, SC, UT, WY | |

| Unusable | >50% | Any value | 4 | AL, KS, RI, TN |

Notes: *T-MSIS includes all 50 states, the District of Columbia (DC), and the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico (PR) and the Virgin Islands (VI). A DQ assessment is not available for VI in the 2020 TAF (Data Version: Release 1) due to incomplete/unavailable data. VI is therefore the only state/territory categorized as “Unclassified” in the 2020 TAF (Data Version: Release 1), and does not appear in Table 2.

Visualizing T-MSIS Data in the DQ Atlas

The DQ Atlas enables users to generate maps that compare the quality of T-MSIS data between states across different topics, such as race/ethnicity, age, income, and gender (see Figure 1). Visualizing T-MSIS data in this manner can help researchers quickly assess the completeness of a single variable as well as the relative completeness (or incompleteness) of certain variables compared to others. For example, in the 2020 TAF Data Release 1, all states and territories received a “low concern” rating for age data, whereas only 29 states and territories received a “low concern” rating for family income.

Figure 1. Data Quality Assessments of Beneficiary Information by U.S. State/Territory

Notes: Green = low concern; yellow = medium concern; orange = high concern; red = unusable; grey = unclassified.

Source: Medicaid.gov. (n.d.). DQ Atlas: Race and Ethnicity [2020 Data set: Version: Release 1]. Available from https://www.medicaid.gov/dq-atlas/landing/topics/single/map?topic=g3m16&tafVersionId=25. Accessed January 5, 2023.

Looking Ahead

Increasingly, a wide diversity of voices from non-profits, health insurers, state-based marketplaces, and policymakers have called for improving the collection of race, ethnicity, and language data, often with the goal of advancing health equity. CMS’s efforts to improve the quality and availability of T-MSIS data reflect this nationwide movement toward data collection practices that more accurately capture the diversity of the U.S. population.

In June 2022, CMS released updated technical instructions for reporting beneficiary race, including clarification on how to report race information for beneficiaries who report multiple races. That same month, the Biden Administration announced its intent to revise the federal government’s standards for surveying race and ethnicity – a policy change that is expected to result in disaggregated categories for Hispanic individuals and people of Middle Eastern or North African descent.4

California and New York have enacted historic policies to disaggregate race/ethnicity data within the past year: California now requires state agencies to list a separate category for Black descendants of enslaved people when collecting state employee data; and New York now requires state agencies to disaggregate Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander data into more granular collection categories (e.g., Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian, Samoan).5,6 It is likely that other states will follow these data disaggregation practices in the years ahead as public awareness of issues related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and racial justice continues to grow.

Sources

1 Medicaid.gov. Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS). Retrieved October 20, 2022, from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/data-systems/macbis/transformed-medicaid-statistical-information-system-t-msis/index.html#

2 Medicaid.gov. September 2022 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights. Retrieved on January 5, 2023, from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html

3 Saunders, H., & Chidambaram, P. (April 28, 2022). Medicaid Administrative Data: Challenges with Race, Ethnicity, and Other Demographic Variables. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-administrative-data-challenges-with-race-ethnicity-and-other-demographic-variables/

4 Wang, H.L. (June 15, 2022). Biden officials may change how the U.S. defines racial and ethnic groups by 2024. NPR. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/2022/06/15/1105104863/racial-ethnic-categories-omb-directive-15

5 Diaz, J. (August 16, 2022). California becomes the first state to break down Black employee data by lineage. NPR. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/2022/08/16/1117631210/california-becomes-the-first-state-to-break-down-black-employee-data-by-lineage

6 The New York State Senate. (December 22, 2021). Assembly Bill A6896A. Retrieved November 2, 2022, from https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/A689

Blog & News

Examining Gender-Based Discrimination in Health Care Access by Gender Identity in Minnesota

December 9, 2022:Authors: Jeremy Duval, Natalie Mac Arthur, Kathleen Call

DefinitionsCisgender/cis: A person whose gender identity corresponds with their sex assigned at birth. Transgender/trans: A person whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. Non-binary: An umbrella term for a person whose gender identity is not binary (male or female). |

Introduction

Many barriers exist to creating an equitable health care experience for LGBTQ+ individuals. One critical barrier is gender-based discrimination from providers within health care systems. The biennial 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) asked respondents how often their gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression causes health care providers to treat them unfairly. We compared rates of gender-based discrimination and health care access in the Minnesota adult population and examined differences in access to care among cisgender (cis) and gender minorities who report gender-based discrimination (see Definition Box). We explored the impact of gender-based discrimination on health care access by comparing access rates among people who did and did not experience discrimination for cis men, cis women, transgender and non-binary populations in Minnesota.

Results

The majority (58.9%) of transgender (trans) and non-binary respondents reported experiencing gender-based discrimination from health care providers in 2021—a stark contrast from the statewide average of 6.0% (Figure 1). Cis women also reported gender-based discrimination (7.7%) above the population average, while cis men were less likely to experience this form of discrimination (2.9%). Gender-based discrimination was especially high for both non-binary (63.9%) and trans (48.8%) respondents. Due to sample size limitations, these populations were combined in the remainder of our analyses.

Figure 1. Unfair treatment from health care providers based on gender in Minnesota

^ Rate significantly different from All Adults at the 95% confidence level.

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

We also found differences in health care access among trans and non-binary people compared with the adult Minnesota population, particularly for confidence in getting care and forgoing needed care due to cost (Figure 2). We found that trans and non-binary respondents were similar to cis men in rates of having a usual source of care and having a medical visit (non-emergency) in the past year. Compared with the adult population in Minnesota, cis men were more likely to lack these forms of care, while cis women had better access to regular medical visits and a usual source of care. However, differences from the state average did not reach significance for trans and non-binary respondents, likely due to small sample size. Nearly a third (30.1%) of trans and non-binary adults had low confidence in getting necessary care compared to an average of 11.8% for adults in Minnesota. Over half (57.1%) of trans and non-binary people reported forgone care—more than double the average (26.2%).

Figure 2. Health care use and barriers to care

^ Rate significantly different from All Adults at the 95% confidence level.

† Estimate may be unreliable due to limited data (relative standard error greater than or equal to 30%).

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

Figure 3. Experiences of gender-based discrimination associated with barriers to health care access

* Significant difference within a given subpopulation between rates of people who experienced unfair treatment and those who did not.

† Estimate may be unreliable due to limited data (relative standard error greater than or equal to 30%).

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

Discussion

A worryingly high proportion of trans and non-binary adults reported gender-based discrimination and had forgone care or did not have confidence in getting needed care. This lack of confidence could be in part due to experienced or anticipated discrimination within a health care setting. Barriers to care were especially high among those who had experienced gender-based discrimination, which suggests that discrimination has a serious negative impact on health care access for trans and non-binary people.

We found higher rates of gender-based discrimination (58.9%) among trans and non-binary adults in Minnesota in 2021 compared to previously published literature on gender-based discrimination. National data indicate that between 20% and 40% of LGBTQ+ Americans experience discrimination while accessing health services (Kattari & Hasche, 2016), (Kachen & Pharr, 2020), (Penrose et al, 2020), (Rodriguez, Agardh & Asamoah, 2018), (Shires & Jaffee, 2015). Additionally, over 20% of the LGBTQ+ population avoided seeking health care due to anticipated discrimination (Kcomt et al, 2020). Notably, the majority of previously published estimates of trans peoples’ experiences of health care discrimination come from the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, which was conducted in 2016 and provides rich data, but for a specialized and non-probability sample. Such data are not considered generalizable. A strength of the MNHA survey is that it measures discrimination using a probability sample of adults reporting their gender identity.

Gender-based discrimination is just one factor affecting health care access. Gender minorities may additionally face disproportionate rates of other key barriers to access, such as lack of insurance coverage (Gonzales & Henning-Smith, 2017). Regardless, we found large gaps in health care access for trans people, non-binary people, and all people who experienced gender-based discrimination.

Conclusion

When the majority of a population is experiencing discrimination within health care systems, it is clear that change is necessary. Our data, based on a probability sample of Minnesotans, helps address gaps in knowledge about barriers transgender and non-binary adults face in accessing health care. The high rates of gender-based discrimination among gender minorities illustrate that gender-inclusive data collection is important for health equity.

However, quantifying rates of discrimination only scratches the surface of the true problem. Because of the limited sample size of gender minority adults, we were unable to explore the role of other social factors in gender-based discrimination and health care barriers by gender identity. Race, ethnicity, and class likely intersect to exacerbate experiences of discrimination and barriers to care for gender minorities. For example, Black and American Indian/Alaskan Native transgender women face disproportionate rates of victimization, and these experiences may impact their health care needs and intensify barriers to accessing care (Reisner, 2018). In this analysis, we only looked at gender identity; our future studies will look at sexual orientation with a similar lens and examine these two together.

One of the largest barriers to understanding discrimination and its effects on health access is data collection. Not all surveys collect and report inclusive data on gender identity, which makes it very hard to track access for trans and non-binary people. Even when gender-inclusive data are available, gender-based discrimination is rarely measured. Direct measurement of discrimination is essential for monitoring rates of discrimination in health care settings and associated barriers to care (Lett et al., 2022).

In Minnesota, state-level policies make this type of measurement possible. Historically, Minnesota has strong anti-discrimination laws in place to protect gender-diverse individuals. For example, Minnesota was one of the first states to allow an “X” option for gender on licenses (Walsh, 2018). Yet, we found alarmingly high reports of gender-based discrimination in health care among gender minorities in this state. The level of gender-based discrimination may be even higher in other states with less inclusive policies. Consequently, our results suggest that on a national level, gender-based discrimination in health care may affect a substantial number of Americans.

Understanding the full scope of gender-based discrimination in Minnesota and across the U.S. should be a priority in future research to support health equity. Our data contributes to the base of knowledge regarding gender-based discrimination in health care and its correlation with issues of health care access. Our findings highlight the need for more expansive research and policy changes in these areas.

Methods

Data are from the 2021 Minnesota Health Access (MNHA) survey, which is a biennial population-based survey on health insurance coverage and access conducted in collaboration with the Minnesota Department of Health. We limited the analysis to adults responding for themselves about experiences of discrimination and access (n=10,003); we excluded proxy reports (e.g., a household member answering for a spouse or roommate). Tests for statistical significance were conducted at the 95% confidence level.

Check out our companion blog "Examining Discrimination and Health Care Access by Sexual Orientation in Minnesota".

References

Gonzales, G., & Henning-Smith, C. (2017). Barriers to Care Among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Adults. The Milbank quarterly, 95(4), 726–748. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12297

Kachen, A., & Pharr, J. R. (2020). Health Care Access and Utilization by Transgender Populations: A United States Transgender Survey Study. Transgender health, 5(3), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2020.0017

Kattari, S. K., & Hasche, L. (2016). Differences Across Age Groups in Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People's Experiences of Health Care Discrimination, Harassment, and Victimization. Journal of aging and health, 28(2), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315590228

Lett E., Asabor E., Beltrán S., Cannon A.M., Arah O.A. (2022). Conceptualizing, Contextualizing, and Operationalizing Race in Quantitative Health Sciences Research. Ann Fam Med 20(2):157-163. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2792

Movement Advancement Project. "Equality Maps: Housing Nondiscrimination Laws." https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/non_discrimination_laws/housing. Accessed 11/07/2022.

Reisner, S. L., Bailey, Z., & Sevelius, J. (2014). Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the US. Women & health, 54(8), 750-767.

Shires, D. A., & Jaffee, K. (2015). Factors associated with health care discrimination experiences among a national sample of female-to-male transgender individuals. Health & social work, 40(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlv025

Walsh, P. (2018, October 3). Minnesota Now Offers 'X' for Gender Option on Driver's Licenses. Star Tribune. Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://www.startribune.com/minnesota-now-offers-x-for-gender-option-on-driver-s-licenses/494909961/.

Blog & News

SHADAC Researchers Co-Author Maternal and Child Health Journal Article on Medical Home Contributions to Child Health Outcomes

December 9, 2022:SHADAC researchers Natalie Mac Arthur and Lynn Blewett recently published a journal article in Maternal and Child Health Journal that examines the medical home model—a widely accepted model of team-based primary care—and its unique contributions to child health outcomes.

Their analysis drew on data from the 2016-2017 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to assess five key medical home components–usual source of care, personal doctor/nurse, family-centered care, referral access, and coordinated care–and their associations with child outcomes. Health outcomes included emergency department (ED) visits, unmet health care needs, preventive medical visits, preventive dental visits, health status, and oral health status.

Key Findings

- Results showed that children who were not white, living in non-English households, with less family income or education, or who were uninsured had lower rates of access to a medical home and its components.

- A medical home was associated with beneficial child outcomes for all six of the outcomes and the family-centered care component was associated with better results in five outcomes.

- ED visits were less likely for children who received care coordination.

These findings highlight the role of key components of the medical home model and the importance of access to family-centered health care that provides needed coordination for children of all backgrounds. Health care reforms should consider disparities in access to a medical home and specific components and the contributions of each component to provide quality primary care for all children. Understanding the role of medical home components contributes to the refinement of the model and can inform health care policy efforts to improve health equity for all children.

Read the full article in the Maternal and Child Health journal.

Blog & News

SHADAC in AJPH: Insurance-Based Discrimination Reports and Access to Care Among Non-Elderly U.S. Adults, 2011-2019

December 8, 2022:This journal article was originally published in the American Journal of Public Health (AJPH).

Authors: Kathleen Thiede Call, PhD, Giovann Alarcon-Espinoza, PhD, MPP, Natalie Schwer Mac Arthur, PhD, MAc, and Rhonda Jones-Webb, DrPH

SHADAC researchers and external co-authors recently published an article in the American Journal of Public Health (AJPH) that examines rates of insurance-based discrimination for nonelderly adults with private, public, or no insurance between 2011 and 2019, a period marked by passage and implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and threats to it.

Using 2011–2019 data from the biennial Minnesota Health Access Survey, the study found that about 4,000 adults aged 18 to 64 report insurance-based discrimination experiences. Using logistic regressions, the authors examined associations between insurance-based discrimination and (1) sociodemographic factors and (2) indicators of access.

Key Findings

- On average, approximately 10% of nonelderly adults reported insurance-based discrimination, although there was a statistically significant increase from 7.7% in 2015 to 11.0% in 2017.

- Reports of insurance-based discrimination remained remarkably stable within each coverage type between 2011 and 2019:

- Uninsured adults ranged between 24.7% to 28.1%

- Adults with public coverage ranged between 18.4% to 24.0%

- Adults with private coverage ranged between 3.0% to 5.4%

- Compared with adults with private insurance (4% on average), insurance-based discrimination was 5 or 6 times higher for adults with public insurance (21% on average) and about 7 times higher for adults with no insurance (27% on average).

- There was little association between insurance-based discrimination and having a usual source of care. However, insurance-based discrimination persistently interfered with confidence in getting needed care and reports of forgone care.

These findings indicate that policy changes from 2011 to 2019 affected access to health insurance, but high rates of insurance-based discrimination among adults with public insurance or no insurance were impervious to such changes. Stable rates of insurance-based discrimination during a time of increased access to health insurance via the ACA suggest deeper structural roots of healthcare inequities.

Read the full American Journal of Public Health article to learn more about the study methods and findings. A copy of this AJPH article is also available upon request.