Blog & News

Disability Health Care Data and Information: Resources from SHADAC

August 08, 2024:- Unfair treatment in health care settings, at work, or when applying for public benefits

- Adults with disabilities are more likely to live in poverty compared to adults with no disability

- People with a disability often have increased medical expenses, with a study from the National Disability Institute estimating that a U.S. household containing an adult with a disability must spend an estimated 28% more income to obtain the same standard of living as a household with no disability

- Those with disabilities have twice the risk of developing chronic health conditions like depression, diabetes, asthma, and poor oral health

Federal Survey Sample Size Analysis: Disability, Language, and Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

- People who indicated sexual orientation or gender identity (SOGI)

- People with language access needs, and

- People with disabilities

Collection of Self-Reported Disability Data in Medicaid Applications: A Fifty-State Review of the Current Landscape (SHVS Brief)

State Health Compare Disability Breakdowns

Housing Affordability Matters: Unaffordable Rents Infographics Updated with 2022 Data

Minnesota Community and Uninsured Profile

Stay Informed on Disability Health Data Resources and Information

Blog & News

Provider Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity: Experiences of Transgender/Nonbinary Adults and Sexually Minoritized Adults in Minnesota

September 03, 2024:Background

Understanding the experiences of people with minoritized sexual and gender identities matters for public health. Compared with straight and cisgender adults, these populations face inequitable barriers to health care access1,2 and disparities in health outcomes, including mental and physical health, activity limitations, and chronic conditions.3,4 Accordingly, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) data collection is foundational in advancing population health and health equity in order to better understand the disparities and inequities these populations face.

As highlighted in our previous blogs, one focused on populations by sexual orientation and the other focused on populations by gender identity, reports of discrimination from health care providers based on sexual orientation or gender identity are high among people with minoritized sexual and gender identities. This discrimination is associated with barriers to health care access. For example, individuals who report discrimination may not receive proper treatment from discriminatory providers, and they may forgo or delay health care to avoid discrimination. Across populations, experiencing discrimination has been shown to negatively affect mental and physical health.5

In this blog, we build on these results by pooling two years of data to look at people’s experiences at the intersection of minoritized sexual and gender identities in reports of provider discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation. We used a survey question asking, ‘how often their gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression cause health care providers to treat them unfairly.’ Our analysis also illustrates how the commonly used measures for sexual orientation do not adequately encompass the range of options for sexually minoritized people, and how these limitations disproportionately impact the transgender and nonbinary populations.

Study Approach

We used 2021-2023 data from the biennial Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA). See Methods here.

Results

Among all adults in Minnesota, over half of the transgender/nonbinary population (56.3%) reported experiencing provider discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity – significantly higher compared with cisgender adults’ reported experiences of discrimination (6.7%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Rates of SOGI-Based Provider Discrimination by Sexual Orientation Among Cisgender Adults and Transgender/Nonbinary Adults in Minnesota, 2021-2023.

| Cisgender | Transgender/Nonbinary | ||

| All Adults (18+) | 6.7% | 56.3% | * |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Straight | 4.9% | -- | -- |

| Gay or Lesbian | 24.1% | 88.1% | * |

| Bisexual or Pansexual | 31.6% | 40.5% | |

| None of These | 23.9%† | 66.2% | * |

* Significant difference between cisgender and transgender/nonbinary adults in reports of provider discrimination.

† Estimate may be unreliable due to limited data (relative standard error greater than or equal to 30%).

-- Estimate not available to limited data.

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021-2023 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

When delving into experiences of provider discrimination among people with diverse gender and sexual identities, we found that reports of provider discrimination from transgender/nonbinary adults who identified as gay/lesbian or ‘none of these’ were significantly higher than for cisgender adults who identify as gay/lesbian or ‘none of these.’

Specifically, provider discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation was reported by:

- Nearly 9 in 10 transgender/nonbinary adults (88.1%) and about one in four (24.1%) cisgender adults who identified as gay/lesbian

- Two thirds of transgender/nonbinary adults (66.1%) and about a quarter of cisgender adults (23.9%) that chose the ‘none of these’ option for sexual orientation

Provider discrimination was also high for people who identified as bisexual/pansexual, and, for this group, not significantly different for transgender/nonbinary adults (40.5%) and cisgender adults (31.6%).

The lowest rates of provider discrimination were reported by straight cisgender adults at 4.9%.

Please note that sample sizes were limited, particularly for comparing straight or bisexual/pansexual adults by gender.

Discussion

Consistently across sexual orientations, reports of provider discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation were higher for transgender/nonbinary adults compared with cisgender adults. This suggests that discrimination associated with sexual minoritization may disproportionately impact transgender/nonbinary populations.

Individuals that experience multiple minoritized identities must contend with discrimination on multiple levels. For example, someone may experience discrimination based on a combination of their sexual orientation, gender identity, race, and/or disability status. Looking at the data from this study, we can illustrate this idea looking at provider discrimination reported by gay/lesbian cisgender adults and gay/lesbian transgender/nonbinary adults. Both of these groups share the same sexual orientation, but differ in gender identity. The group with multiple minoritized identities, the gay/lesbian transgender/nonbinary group, reported significantly higher rates of discrimination (88.1%) compared to cisgender gay/lesbian adults (24.1%), which may be related to their multiple levels of marginalization.

Overall, though, our analysis finds that discrimination remains alarmingly high across all groups of people with minoritized sexual and/or gender identities. Looking across the Minnesota population, this study documents provider discrimination among both transgender/nonbinary and cisgender sexual minorities, including people who identify as gay/lesbian, bisexual/pansexual, or ‘none of these.’

Our study also shows the importance of providing data for groups outside of the largest categories such straight, gay/lesbian, or bisexual. For example, by pooling multiple years of data, we were able to produce estimates for gender and sexual minorities including people who responded ‘none of these’ for sexual orientation. This latter group is important to highlight considering the wide range of sexual identities beyond gay/lesbian, straight, and bisexual. Reports of discrimination were high for both transgender/nonbinary and cisgender people who responded ‘none of these’ for sexual orientation, and significantly higher for the transgender/nonbinary people compared with cisgender.

This study highlights continued evidence of health care provider discrimination in Minnesota, with transgender/nonbinary sexual minorities being particularly impacted. Policies are urgently needed to address this discrimination, particularly for transgender/nonbinary Minnesotans who already face barriers to health care access and disparities in health outcomes compared to cisgender adults.

METHODS

Data

The 2021-2023 Minnesota Health Access (MNHA) survey is a biennial population-based survey on health insurance coverage and access conducted in collaboration with the Minnesota Department of Health. We limited the analysis to adults responding for themselves about experiences of discrimination (n=17,828), and we excluded proxy reports (e.g., a household member answering for a spouse or roommate).

Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the MNHA Survey

To study discrimination, we looked at a survey question that asks respondents ‘how often their gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression cause health care providers to treat them unfairly.’ Responses of ‘never’ were coded as no discrimination, and responses of ‘always,’ ‘usually,’ or ‘sometimes’ were coded as discrimination.

Sexual Orientation Measures in the MNHA Survey

Similar to other surveys that collect sexual orientation data, the MNHA asks about sexual orientation using three main response options: ‘gay or lesbian’; ‘straight, that is, not gay or lesbian’; and, ‘bisexual or pansexual.’ Survey respondents could also select ‘don’t know’ or ‘none of these,’ with an option to write in their own answer. We reviewed write-in responses and, when possible, recoded these responses to align with the existing categories.

Recoding write-in responses was a key step in reducing the risk of misclassification in order to include people who selected ‘none of these’ for sexual orientation in analysis. Some straight adults are unfamiliar with terminology for sexual orientation, which can lead to inaccurate responses.6 We reclassified inappropriate write-in answers (such as man, woman, married, or offensive comments) as ‘refused.’

After this step in cleaning the data, we tabulated results separately for two groups: people who responded ‘none of these’ with no write-in, and those who responded ‘none of these’ with an LGBTQ+ write-in response such as ‘queer’ or ‘asexual.’ Rates were similar, which helped to justify combining these subgroups into a single ‘none of these’ variable to improve sample size and produce estimates of reported discrimination for this subpopulation.

MNHA measures of sexual orientation were generally consistent with current best practices (for more information on SOGI data collection practices in Medicaid click here, and click here for our brief on federal survey sample size analysis), our analysis highlights some limitations of commonly used survey measures for sexual orientation. A small difference in the MNHA from typical measures is the inclusion of ‘bisexual or pansexual’ rather than only ‘bisexual’ as a response option. Current recommendations suggest using the phrasing, ‘I use a different term,’ rather than ‘none of these’ as a response option.7

Gender Identity Measures in the MNHA Survey

In 2023, the MNHA switched from a single question measuring gender to a two-step question asking first, ‘how do you describe your gender,’ and second, ‘are you transgender.’ As described in a previous blog, this approach was developed by the Oregon Health Authority through extensive community engagement and has advantages of being clear and inclusive.8 Response options for gender were:

- Man

- Woman

- Gender non-binary or two-spirit

- Agender/no gender

- Another gender (optional write in response)

In contrast, 2021 response options included ‘transmale/transman’ and ‘transfemale/transwoman’ listed after ‘male/man’ and ‘female/woman,’. Although current best practice recommendations for federal surveys list ‘transgender’ as response option after male/female, this approach has the limitation of implying that being transgender is ‘other’ and mutually exclusive from male/female. Similarly, the two-step question currently recommended for federal surveys asks about ‘sex assigned at birth,’ which may be perceived as invalidating and adds cognitive burden, especially for people with low literacy. Using accessible language in survey questions supports user experiences and overall response rates, and helps to reduce data quality problems such as item non-response and misclassifications. Guidance developed by the state of Oregon offers an inclusive approach to measuring gender on population surveys.

Analysis

We tabulated gender and sexual orientation based discrimination by sexual orientation for cisgender and transgender/nonbinary adults in Minnesota. For transparency, we present results for all response categories, even if estimates must be suppressed due to lack of data. Tests for statistical significance were conducted at the 95% confidence level.

References

[1] Bosworth, A., Turrini, G., Pyda, S., Strickland, K., Chappel, A., De Lew, N., Sommers, B.D.. (June 2021). Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care for LGBTQ+ Individuals: Current Trends and Key Challenges. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-07/lgbt-health-ib.pdf

[2] Kates, J., & Ranji, U. (2024). Health Care Access and Coverage for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community in the United States: Opportunities and Challenges in a New Era. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/perspective/health-care-access-and-coverage-for-the-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-lgbt-community-in-the-united-states-opportunities-and-challenges-in-a-new-era/

[3] Baptiste-Roberts, K., Oranuba, E., Werts, N., & Edwards, L. V. (2017). Addressing health care disparities among sexual minorities. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics, 44(1), 71-80.

[4] Feir, D., & Mann, S. (2024). Temporal Trends in Mental Health in the United States by Gender Identity, 2014–2021. American Journal of Public Health, (0), e1-e4.

[5] Pascoe, E. A., & Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 135(4), 531.

[6] Miller, K., & Ryan, J. M. (2011). Design, development and testing of the NHIS sexual identity question. National Center for Health Statistics, 1-33.

[7] Office of the Chief Statistician of the United States. (n.d.). Recommendations on the Best Practices for the Collection of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data on Federal Statistical Surveys. (Washington, D.C.) https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/SOGI-Best-Practices.pdf

[8] Oregon Health Authority. (2021, December 21). OHA/ODHS SOGI Committee Structure and Process used to Develop SOGI Data Recommendations (December 2021). https://www.oregon.gov/oha/EI/Documents/SOGI-Data-Committee-Survey.pdf

Blog & News

LGBT Health Equity: Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data Resources and Information from SHADAC

October 28, 2024:- Less likely to have health insurance coverage

- Less likely to have a regular health care provider

- More likely to delay care

- More likely to report poor quality care and unfair treatment from providers

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data: New and Updated Information on Federal Guidance and Medicaid Data Collection Practices (SHVS Brief)

State Health Compare: Explore Health Data with SOGI Data Breakdowns

- Adults Who Forgo Needed Medical Care Due to Cost

- Adult Smoking

- Adult Excessive Alcohol Consumption

- Adult E-Cigarette Use

- Chronic Disease Prevalence

- Adult Unhealthy Days

- Activities Limited Due to Health Difficulty

- Adults with No Personal Doctor

- Adult Cancer Screenings

- Adult Flu Vaccinations

Gender Based Discrimination in Health Care by Gender Identity in Minnesota

- Over half (57.1%) of trans and non-binary people reported forgone care—more than double the overall average of 26.2%

- Nearly one-third of trans and non-binary adults had low confidence in getting necessary health care—compared to the overall average of 11.8%

Examining Discrimination and Health Care Access by Sexual Orientation in Minnesota

- Both lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual people were more likely to report barriers to health care access

- Bisexual/pansexual people were more likely to report having low confidence in the ability to get needed health care

- Both lesbian/gay or bisexual/pansexual people had significantly higher rates of forgone care

SHADAC Response to 2023 Request for Comments on American Community Survey SOGI Questions

Stay Up to Date on the Latest in SOGI and LGBT Health Data

Blog & News

Social Vulnerability Index in Minnesota: Community and Uninsured Profile Interactive Map Updated with SVI, MNsure Regions, and More

July 02, 2024:SHADAC has made some exciting updates to our resource, “Minnesota’s Community and Uninsured Profile.” This profile, created with funding from the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota Foundation, was designed to provide accessible information to policymakers and community members alike on Minnesota uninsured people and populations.

Along with updating the profile with 2022 American Community Survey data, researchers have also updated and added to the interactive map of Minnesota that allows users to visually explore the information & data, including information on Minnesotan communities' social vulnerability index. Our hope is that this update will make it even easier for people to:

- Explore the varied communities in the state

- Evaluate community needs

- Monitor equity initiatives, and

- Inform strategic planning

Let’s take a look at the major updates we’ve made to both the profile and its accompanying interactive map:

1. Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) Added to Interactive Map at the Zip Code Level

SHADAC Researchers have added Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) ratings to the Minnesota Community and Uninsured Profile Interactive Map. What is SVI, though, and what does it mean for communities in Minnesota and beyond?

SHADAC Researchers have added Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) ratings to the Minnesota Community and Uninsured Profile Interactive Map. What is SVI, though, and what does it mean for communities in Minnesota and beyond?

Social Vulnerability is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as, “the demographic and socioeconomic factors (such as poverty, lack of access to transportation, and crowded housing) that adversely affect communities that encounter hazards and other community-level stressors.” In short, it represents how vulnerable a community is to stressors, whether that’s a natural stressor (like a tornado or hurricane, for example) or human-caused (like a chemical spill, for example).

The Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) quantifies an area’s social vulnerability, assigning a numerical value that allows for comparison of different locations (counties, zip codes, etc.) to understand how different communities may respond to or be affected by hazards and stressors.

The index measures vulnerability based on four overall factors: socioeconomic status (including insurance status, educational status, housing costs, employment, poverty level), household characteristics (like age composition, English language proficiency, etc.), racial & ethnic minority status, and housing type & transportation (like multi-unit structures, mobile homes, access or lack of access to vehicle, public transit, overcrowding, etc.).

This SVI information now lives on the BCBS Minnesota Community and Uninsured Profile’s Interactive Map – users can click on each zip code area on the map revealing that area’s SVI along with other data such as rate of uninsured, population, and more. Find the map here or click on the image of the map.

2. Every Geographic Layer Now Clickable with Basic Stats

Before the latest update, users were only able to click on Zip Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTAs). Now, researchers have made it possible for users to click on various geographic layers. Along with ZCTAs, users can now click to get basic data (population, number of uninsured, and rate of uninsured) by:

- County

- Economic development region

- House district

- Senate district

- MNsure region

- And more

This allows users to view data in a larger variety of ways and view increasingly specific data in a more easily accessible way.

3. Toggle Other Relevant Factors

Researchers also updated the feature allowing users to toggle relevant indicators on the map such as:

- Native American reservation locations & names

- Hospitals

- Schools

- County seat

- And more

These relevant factors can have large impacts on that area’s overall community makeup and social vulnerability. For example, a geographic area that is close in proximity to multiple hospitals may be less socially vulnerable than a rural area that has no hospitals close by.

4. Profile Updated with Latest Available Data

Along with these key updates to the profile’s accompanying interactive map, researchers also recently updated the profile itself with 2022 American Community Survey data. Learn more about the data update in this blog post.

Start Using the Interactive Map to Learn About Minnesota’s Varied Communities

Understanding communities’ needs begins with understanding those communities and the people within them.

The Minnesota Community and Uninsured Profile was created to help people better understand the many diverse communities within the state. It provides users with important data and information that is accessible, specific, and relevant. Its accompanying interactive map puts that data and information into a clear visual space, helping users understand how geographic location impacts communities and their needs throughout the state.

Ready to learn more about the diversity of Minnesotan communities? Start exploring the interactive map here, and check out the full profile at this link.

Publication

Systemic / Structural Ableism: Underlying Factors of Medicaid Inequities Annotated Bibliography

*Click here to jump to the 'Systemic Ableism' annotated bibliography*

The State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and in collaboration with partner organizations is exploring whether a new national Medicaid Equity Monitoring Tool could increase accountability for state Medicaid programs to advance health equity while also improving population health.

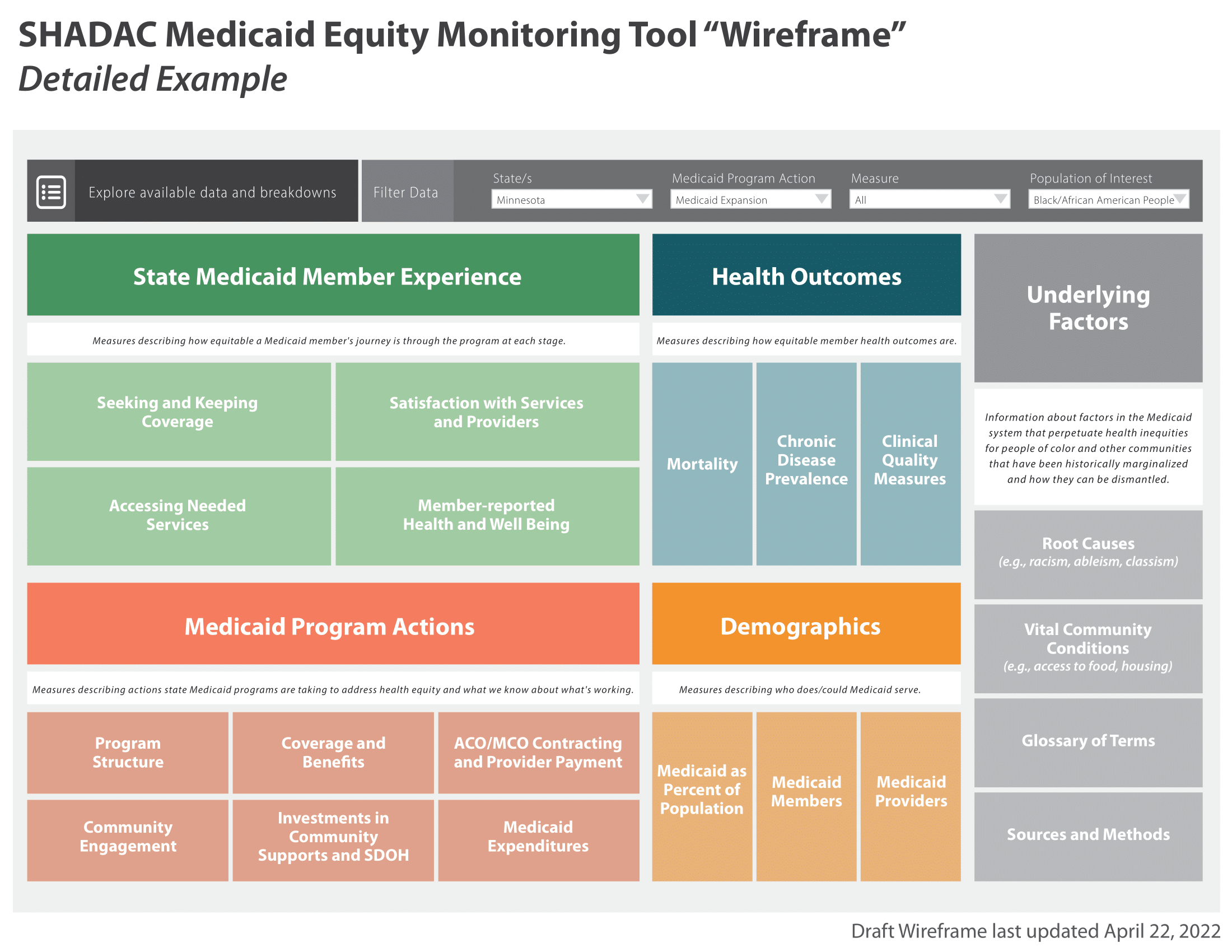

During the first phase of this project, a conceptual wireframe for the potential tool was created. This wireframe includes five larger sections, organized by various smaller domains, which would house the many individual concepts, measures, and factors that can influence equitable experiences and outcomes within Medicaid (see full wireframe below).

While project leaders and the Advisory Committee appointed at the beginning of the project all agree that the Medicaid program is a critical safety net, they specifically identified the importance and the need for an “Underlying Factors” section of the tool. This section aims to compile academic research and grey literature sources that explain and provide analysis for the underlying factors and root causes that may contribute to inequities in Medicaid.

|

|

|

- Historical context of Medicaid inequities

- Information on how underlying factors perpetuate inequities in Medicaid

- Potential solutions for alleviating inequities within Medicaid

Once selected, researchers compiled sources in an organized annotated bibliography, providing a summary of each source and its general findings. This provides users with a curated and thorough list of resources they can use to understand the varied and interconnecting root causes of Medicaid inequities. Researchers plan to continually update this curated selection as new research and findings are identified and/or released.

Sections of the full annotated bibliography include:

- Systemic Racism

- Systemic / Structural Ableism

- Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Gender Affirming Care Discrimination

- Reproductive Oppression in Health Care

- Impact on Vital Community Conditions

This page is dedicated to a single section from the full annotated bibliography:

Systemic Ableism

Underlying Factors Annotated Bibliography: Systemic / Structural Ableism

Have a source you'd like to submit for inclusion in our annotated bibliography? Contact us here to propose a source for inclusion.

Click on the arrows to expand / collapse each source.

Friedman, C., & VanPuymbrouck, L. (2019). The relationship between disability prejudice and Medicaid home and community-based services spending. Disability and Health Journal, 12(3), 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.01.012

Author(s): Carli Friedman, Director of Research for The Council on Quality and Leadership (CQL) at the University of Washington; Laura VanPuymbrouck, Assistant Professor of Occupational Therapy at Rush University

Article Type: Peer-reviewed journal

This peer reviewed article summarizes findings from a quantitative study exploring the association between ableism in the U.S. and Medicaid spending on long term services and supports. It begins with historical context about deinstitutionalization of people with disabilities and the history of Medicaid as both a primary payer for long-term care and an insurer for people with disabilities. Despite research indicating community living has more benefits than institutions, investments in home and community-based services vary state to state; authors hypothesize that an association exists between stereotypical attitudes toward people with disabilities (i.e., as dependent, a drain, not capable) and state decision making. Using CMS expenditure data and survey data from the Disability Attitudes - Implicit Association Test, authors found a negative association between state prejudice scores and state funding of home health and community-based services. While causality cannot be assumed, authors conclude by stressing the importance of understanding how disability prejudice is embedded into our society, and how it may influence Medicaid and other policy decisions. These findings are a call to advocate for increased investment in community services and to promote advocacy for the health and well-being of people with disabilities.

Earl, E. (2023). Promoting Health Care Equity: The Instrumentality of Medicare and Medicaid in Fighting Ableism Within the American Health Care System. Seton Hall Law Review: Vol. 53: Iss. 5, Article 9. Available at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/shlr/vol53/iss5/9

Author(s): Emmalise Earl, Seton Hall University, Judicial Law Clerk in New Jersey Court System

Article Type: Peer-reviewed journal

This article discusses long-standing systemic issues with having accessible health care tools and equipment for people with physical disabilities. Despite the passage of the American Disabilities Act in 1973, which requires hospitals and clinics to have physically accessible equipment for care for all individuals regardless of mobility status, the Act has gone loosely enforced for decades according to the author. Lack of accessible equipment for routine checkups, such as scales and exam tables, results in incomplete examinations, later and more severe diagnoses due to inability to screen those with mobility related disabilities, as well as an exacerbation of current diagnoses due to incomplete or less effective treatment. The author states that “without more aggressive enforcement, these circumstances are not likely to change”. The author uses the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals as an exemplar for what is needed to uphold accessibility standards. The VA requires all new medical equipment to be approved as accessible by their Access Board. The author also describes specific program actions that the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services needs to take in enforcing equitable access to medical equipment. For Medicaid in particular, the author suggests that state Medicaid agencies adopt and enforce standards that facilities and providers must follow in order to participate in the Medicaid program. The authors also suggest leveraging tax incentives to overcome financial barriers to accessibility.

Valdez, R. S., & Swenor, B. K. (2023). Structural Ableism — Essential Steps for Abolishing Disability Injustice. The New England Journal of Medicine, 388(20), 1827–1829. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2302561

Author(s): Rupa S. Valdez, the Departments of Public Health Sciences and Engineering Systems and Environment, University of Virginia; and Bonnielin Swenor, the Disability Health Research Center, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University

Article Type: Peer-reviewed journal perspective

This article discusses the details of systemic ableism and its effects on those with intellectual and/or physical disabilities. The authors maintain that this underlying factor of health inequities is often ignored in health care and research spaces. In addition, more attention is needed on the ways structural ableism interacts with other forms of oppression. The core purpose of this article is to highlight achievable and actionable solutions for alleviating bias and discrimination of those with disabilities. Proposed solutions include establishing measures of structural ableism within research and providing accessibility options within physical environments (e.g. streets & roadways, buildings, neighborhoods, and cities). The authors also emphasize a need for the adaptation of measures of structural racism plus the addition of new measurement domains. Of particular importance for the authors is measuring both the funding allocated for home and community based services within the Medicaid program as well as measuring the rate of violations of the Olmstead decision, which entitles those with disabilities to community integration and community-based services. Consideration of qualitative methods and community partnership in this work is also crucial for creating actionable and effective solutions to issues of systemic ableism.

[1] Valdez, R. S., & Swenor, B. K. (2023). Structural Ableism — Essential Steps for Abolishing Disability Injustice. The New England Journal of Medicine, 388(20), 1827–1829. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2302561