Blog & News

Telehealth Visit Data, ACEs Data, Opioid Sales, and More Updated on State Health Compare

June 06, 2024:National Survey of Children’s Health Data (NSCH)

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are traumatic events that occur during childhood, and include physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, amongst others. These experiences can have long-term impacts on health and wellness long after childhood.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are traumatic events that occur during childhood, and include physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, amongst others. These experiences can have long-term impacts on health and wellness long after childhood.National Health Interview Survey Data (NHIS)

Made Changes to Medical Drugs (NHIS)

‘Made Changes to Medical Drugs’ is defined as the rate of individuals who made changes to medical drugs because of cost during the past twelve months by age for the civilian non-institutionalized population. Asking a medical provider to switch to a cheaper medication, taking less medication than prescribed, skipping dosages, using alternative therapies as a replacement, and delaying refills are all examples of how someone could make changes to medical drugs due to cost. Making changes such as these can have negative impacts on both short- and long-term health.

‘Made Changes to Medical Drugs’ is defined as the rate of individuals who made changes to medical drugs because of cost during the past twelve months by age for the civilian non-institutionalized population. Asking a medical provider to switch to a cheaper medication, taking less medication than prescribed, skipping dosages, using alternative therapies as a replacement, and delaying refills are all examples of how someone could make changes to medical drugs due to cost. Making changes such as these can have negative impacts on both short- and long-term health.Trouble Paying Medical Bills (NHIS)

This measure tracks the percentage of people who had trouble paying off their medical bills in the last year. Like the ‘Made Changes to Medical Drugs’ measure, this can help understand and track health care affordability in the United States. This is especially relevant as the United States has some of the highest health care costs in the world.

This measure tracks the percentage of people who had trouble paying off their medical bills in the last year. Like the ‘Made Changes to Medical Drugs’ measure, this can help understand and track health care affordability in the United States. This is especially relevant as the United States has some of the highest health care costs in the world.Had Emergency Department Visit (NHIS)

Visits to the Emergency Department (ED) (also called the Emergency Room) are often costly and, in a surprisingly large number of cases, preventable. It’s estimated that between 13% and 27% of ED visits could be managed in primary care offices, clinics, and/or urgent care centers.

Visits to the Emergency Department (ED) (also called the Emergency Room) are often costly and, in a surprisingly large number of cases, preventable. It’s estimated that between 13% and 27% of ED visits could be managed in primary care offices, clinics, and/or urgent care centers. Had Telehealth Visit (NHIS)

Telehealth, also called telemedicine, can expand access to care for many individuals and communities. Telehealth services conducted by phone or by video allow individuals to be connected with a health professional when they cannot get an in-person appointment, cannot safely leave their home, or lack transportation to get to an appointment, among a number of other reasons. Access to telehealth was expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic and has remained a popular way to access care.

Telehealth, also called telemedicine, can expand access to care for many individuals and communities. Telehealth services conducted by phone or by video allow individuals to be connected with a health professional when they cannot get an in-person appointment, cannot safely leave their home, or lack transportation to get to an appointment, among a number of other reasons. Access to telehealth was expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic and has remained a popular way to access care.Had Usual Source of Medical Care (NHIS)

Had General Doctor or Provider Visit (NHIS)

Drug Enforcement Administration ARCOS Data

Sales of Opioid Painkillers

The Opioid Epidemic in the United States is widespread and destructive - since 2000, the annual number of overdose deaths from any kind of drug in the U.S. has multiplied nearly six times over, rising from 17,500 to over 106,000 people in 2021. Opioids caused a majority of these deaths, including both legal drugs and illicit drugs like heroin and fentanyl.

The Opioid Epidemic in the United States is widespread and destructive - since 2000, the annual number of overdose deaths from any kind of drug in the U.S. has multiplied nearly six times over, rising from 17,500 to over 106,000 people in 2021. Opioids caused a majority of these deaths, including both legal drugs and illicit drugs like heroin and fentanyl.Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics

Unemployment Rate

Stay Up to Date with the Latest Data

Other Related Reading:

Blog & News

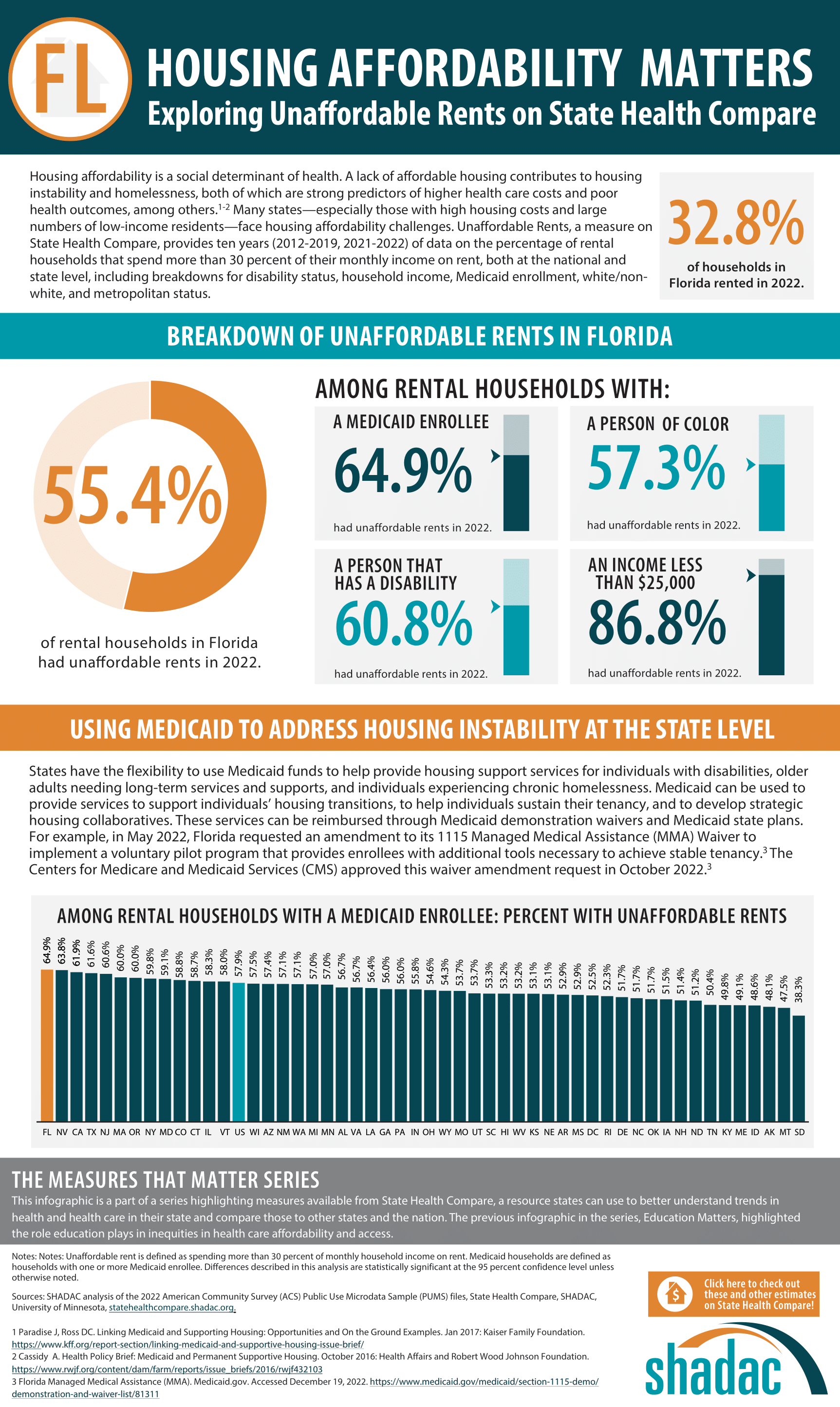

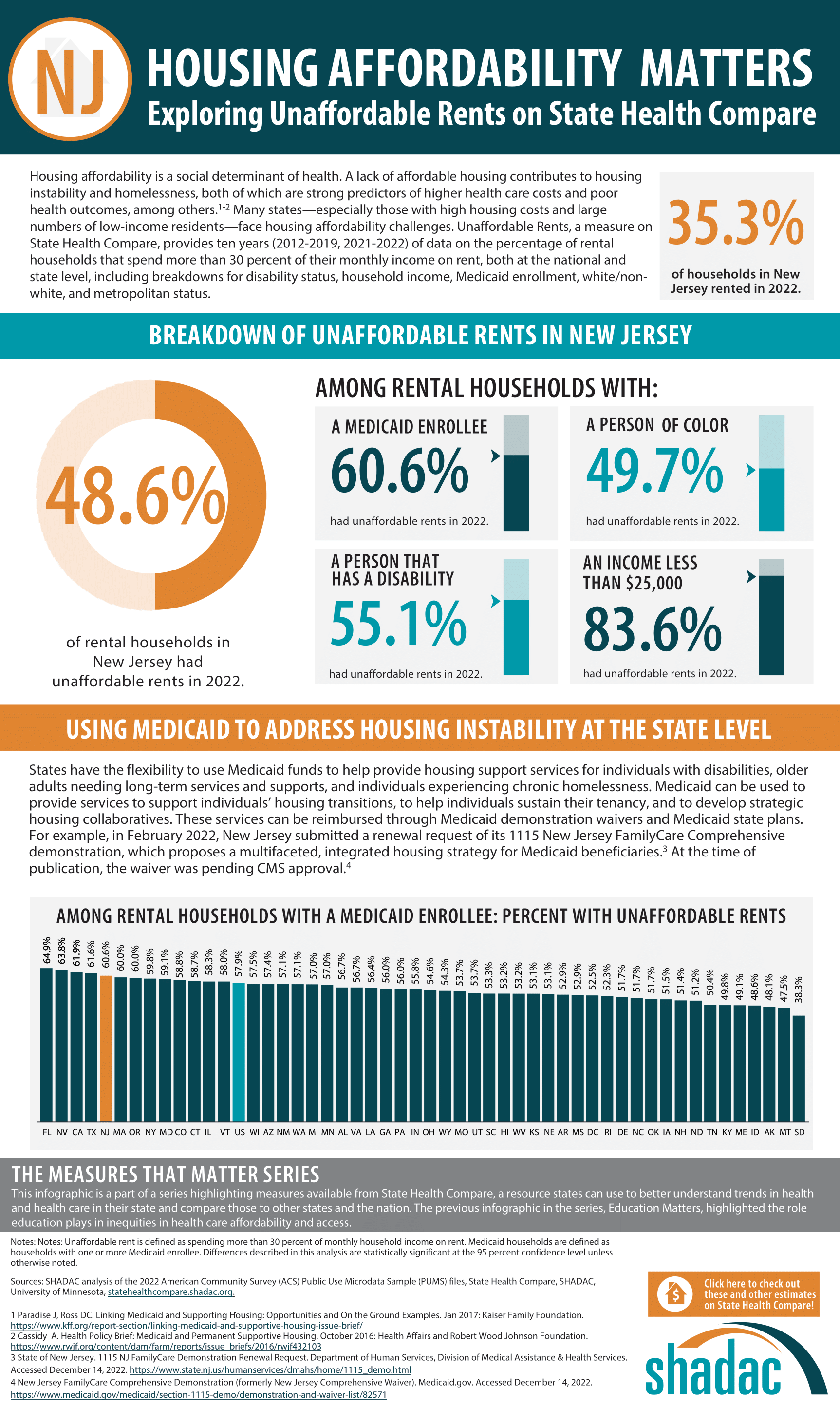

Housing Affordability Matters: Unaffordable Rents Infographics Updated with 2022 Data

June 06, 2024:- By 21% in the West

- By 20% in the South

- By 18% in the Midwest

- By 12% in the Northeast

Affordable Housing and Health: What Is the Connection?

- Access to health care services (or lack of access)

- Education

- Transportation

- Cost of services (healthcare, childcare, utilities, etc.)

- Community support

- Employment opportunities

- Food type, cost, and availability

Housing Affordability Infographics

| United States | California | Florida |

|

|

|

| Nevada | New Jersey | Texas |

|

|

|

Explore More Data on State Health Compare

[1] Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social Determinants of Health: Housing Instability – Literature Summary. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/housing-instability

[2] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2022, June 29). Chart Book: Housing and Health Problems Are Intertwined. So Are Their Solutions. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/housing-and-health-problems-are-intertwined-so-are-their-solutions

Blog & News

Cancer Screening Data: Adults Who Have Received Recommended Cancer Screenings by Coverage Type, Education Level, and Race/Ethnicity in 2022

May 03, 2024:Cancer screening for adults plays a pivotal role in early detection, increasing the chances of successful treatment and preventing thousands of cancer deaths. Despite their life-saving potential, many adults may choose to delay or skip these screenings due to various barriers, such as limited access, transportation issues, fear of diagnosis, or poor understanding of the importance. To effectively address the root causes of underutilization, it's crucial to first understand the landscape of cancer screening rates for varied populations and communities.

State Health Compare offers a comprehensive view of state-level data on adults receiving recommended cancer screenings, for the civilian noninstitutionalized population. This valuable resource provides insights into screening rates across different coverage types, education levels, and racial/ethnic groups. Screenings in this data include:

- Pap smears (cervical cancer screening)

- Colorectal cancer screenings

- Mammograms (breast cancer screening)

In this blog post, SHADAC researchers delve into the breakdowns between the different groups to understand disparities and/or differences of cancer screening rates for various populations. For this analysis, we used data from the 2022 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) on State Health Compare.

Methods

To begin, we first needed to understand the total number of adults who received recommended cancer screenings. We found that, in 2022, 62.6% of US adults received recommended cancer screenings.

We then conducted statistical testing of rates within each of the previously mentioned demographic categories to see if they were significantly higher or lower than the national rate.

Breakdown by Coverage Type

This breakdown examined cancer screening rates for adults by multiple types of insurance coverage.

Some coverage groups had significantly lower cancer screening rates compared to the national rate. Uninsured adults had the lowest rate of cancer screenings in 2022, with 34.0% receiving recommended cancer screenings. Adults that were insured through Medicaid in 2022 also had a significantly lower rate of receiving annual cancer screenings, with a percentage of 57.7%.

Explanations of why these differences occur vary. One possible explanation is the cost of screenings. Those who are uninsured would be required to pay for cancer screenings out of pocket, which can be expensive and cost prohibitive, leading to people forgoing these services. Additionally, many people and families covered under Medicaid are low-income. Even with insurance coverage, individuals may not be able to pay for preventative screenings, have transportation to appointments, be able to take off work or find childcare, etc.

On the other hand, some coverage groups had significantly higher rates of cancer screenings compared to the national rate. Adults with public insurance and Medicare both had significantly higher rates of receiving cancer screenings, with rates of 66.4% and 70.7%, respectively.

Again, possible explanations for this vary. One explanation is that under the Affordable Care Act, Medicare must cover cancer screenings. This guaranteed coverage could explain the higher rate of individuals with Medicare receiving their recommended screenings.

Of those with individual insurance, 59.0% reported receiving recommended screening, which was not statistically different from the US rate. Adults with private and employer/military insurance also did not have a significant rate of annual cancer screenings compared to the US rate, with 62.5% and 63.2%, respectively, reporting receiving annual cancer screenings.

Breakdown by Education Level

Multiple levels of cancer screening data by educational attainment were examined displayed in the graph below.

Two of these groups had significantly lower rates of adults receiving recommended cancer screenings. First was US adults with less than a high school degree, with 47.2% receiving recommended cancer screenings in 2022 (significantly lower than the US rate). The rate for adults who are high school graduates (without further higher education) is also significantly lower than the US rate at 58.8%.

There is no significant difference between the US rate (62.6%) and the rate for adults with some college or an Associate’s degree (63.0%).

Finally, 68.0% of US adults with a Bachelor’s degree or higher reported receiving recommended screenings, which is significantly higher than the US rate. A possible explanation for this higher rate is that individuals with higher educational attainment may be more knowledgeable regarding the importance of receiving preventative care, as well as having the means to seek preventative care.

As individuals with lower educational attainment have lower rates of cancer screening, they also have higher prevalence of modifiable cancer risk factors. Modifiable risk factors for cancer include smoking, excess body weight, alcohol intake, physical inactivity, and poor diet. There are notable educational disparities in cancer prevention in terms of incidence, treatment, and mortality. This reveals the importance of tailoring screening programs and providing educational material to individuals with lower education levels.

Breakdown by Race/Ethnicity

Finally, we were able to create a breakdown of cancer screening rates by racial/ethnic groups.

Note: these groups were selected based on available data. State Health Compare does not have available data for some race/ethnic groups, due to low response rates. However, SHADAC is hopeful this data gap will be addressed in the future in order to conduct equitable analyses.

Compared to the US rate, Hispanic/Latino adults and adults of other/multiple races had significantly lower rates of receiving recommended cancer screenings in 2022, with respective rates of 55.6% and 56.9%.

Approximately two-thirds of both African American/Black adults (64.6%) and White adults (64.9%) reported receiving recommended cancer screenings—both of which are significantly higher than the US rate.

Our analysis shows that there are differences in cancer screening rates between racial/ethnic groups—with our analysis seeing Hispanic and other/multiple race individuals with the lowest screening rates in the US. Other research supports and, in fact, shows even greater inequities than this. Racial disparities not only impact screening rates, but also cancer diagnosis and treatment. Persons of color may receive later stage cancer diagnoses compared to their White counterparts, due to disparities in screening quality and delays in diagnostic evaluations.

Also, persons of color may not be seeking out cancer screening services due to distrust in the healthcare system, discrimination, bias, or unpleasant past experiences.

Final Thoughts

Examining recommended annual cancer screening rates by coverage type, education level, and racial/ethnic group reveals that although the national rate may seem relatively high, there are still groups that face disparities in accessing and utilizing such a vital tool for improving cancer treatment and preventing death.

While this blog has looked at singular category breakdowns, it is important to note the intersectionality between insurance coverage, education level, race/ethnicity, and many other factors. For example, individuals without a high school diploma have the highest uninsurance rates. Race/ethnicity also appears to be correlated with rates of uninsurance. When looking at race and uninsured rates, there are higher uninsurance rates for American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN), Hispanic, Black, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NHPI) individuals compared to their White counterparts.

Therefore, of the groups that have significantly lower rates of cancer screenings compared to the US rate, many individuals may fall into multiple of these sub-categories. Further research and analysis could shed light on how these many factors interact and lead to different (and varied) results and outcomes.

By understanding these disparities, not only can we draw attention to improving public health education and literacy for these populations, but also find meaningful ways to identify and address barriers (individual and structural) that may be hindering these same individuals from accessing the preventative care they need.

Interested in learning more about disparities and health equity in the United States? You can explore the data yourself using the State Health Compare Tool here.

You can also read some of our other products highlighting State Health Compare data, like:

Blog & News

Unemployment Rate Trends of the Past 5 Years: Pre-, Mid-, and Post-Pandemic

April 01, 2024:In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic ended the United States’ decade-long era of economic expansion. Many businesses across industries halted or closed operations, resulting in record-high temporary and permanent job losses – events that have been reflected in unemployment rate trends.

Primarily, unemployment affects people’s economic stability and well-being, but it goes beyond that. Unemployment affects individuals’ access to stable housing, food security, and health insurance coverage and care. Unemployment has also been linked to negative health consequences, with unemployed individuals often reporting feelings of depression and anxiety, and suffering from stress-related illness such as high blood pressure, stroke, heart attack, heart disease, and arthritis more often compared to employed counterparts

Knowing that unemployment affects health and health care access, we wanted to understand how such a seismic event as the pandemic affected unemployment rates. We also wanted to determine what progress has been made in recovery post-pandemic. To do this, SHADAC used our State Health Compare tool’s unemployment measure, looking at data pre- (2018-2019), mid- (2020), and post-pandemic (2021-2022). Keep reading to learn more about our process and key findings.

Unemployment Rate Trends: Overall Rate Rose Sharply During Pandemic

Before the pandemic began, the United States was experiencing what the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) called, “the second longest [period of] economic expansion on record,” with the unemployment rate reaching a 49-year low. Overall, the pre-pandemic national unemployment rates in 2018 and 2019 were 3.9% and 3.7%, respectively. In 2020, what we have termed as during / mid-pandemic, the unemployment rate rose sharply to 8.1%. As time went on, though, unemployment rates began to noticeably decrease, measuring at 5.3% in 2021 and dipping below 2019’s low to 3.6% in 2022.

It is no surprise that national unemployment was at its highest mid-pandemic in 2020 as a result of business closures (both temporary and permanent). However, some heartening news comes from the 2022 data showing a national unemployment rate sitting the lowest it had been in the past five years, and several other key labor market measures also returning to their pre-pandemic levels.

While encouraging, when looking at unemployment rates pre-, mid-, and post-pandemic, it is worthwhile to go beyond the seemingly straightforward, positive picture at the national level in order to understand how different geographic and demographic populations varied in unemployment rates. For our analysis, we looked at unemployment rate by state and by race/ethnicity.

Examining Unemployment Rate Trends by State

The following tables show the five states with the lowest and the highest unemployment rates each year from 2018 to 2022.

| Lowest | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |||||

| Hawaii | 2.4% | North Dakota | 2.4% | Nebraska | 4.2% | Nebraska | 2.5% | North Dakota | 2.1% |

| Iowa | 2.5% | Vermont | 2.4% | South Dakota | 4.6% | Utah | 2.7% | South Dakota | 2.1% |

| New Hampshire | 2.5% | New Hampshire | 2.5% | Utah | 4.7% | South Dakota | 3.1% | Nebraska | 2.3% |

| North Dakota | 2.6% | Utah | 2.6% | North Dakota | 5.1% | Kansas | 3.2% | Utah | 2.3% |

| Vermont | 2.7% | Hawaii | 2.7% | Iowa | 5.3% | Alabama | 3.4% | Missouri | 2.5% |

| Highest | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |||||

| Louisiana | 4.9% | New Mexico | 4.9% | Michigan | 9.9% | Dist. of Columbia | 6.6% | Pennsylvania | 4.4% |

| New Mexico | 4.9% | West Virginia | 4.9% | New York | 10.0% | New Mexico | 6.8% | Delaware | 4.5% |

| West Virginia | 5.3% | Mississippi | 5.4% | California | 10.1% | New York | 6.9% | Illinois | 4.6% |

| Dist. of Columbia | 5.6% | Dist. of Columbia | 5.5% | Hawaii | 11.6% | Nevada | 7.2% | Dist. of Columbia | 4.7% |

| Alaska | 6.6% | Alaska | 6.1% | Nevada | 12.8% | California | 7.3% | Nevada | 5.4% |

Certain unemployment rate trends have remained consistent in the last two years of the post-pandemic period, which could shed light on individual states’ economic recovery post-pandemic. For example, Nebraska and South Dakota have been among the five states with the lowest unemployment rates mid- & post-pandemic, suggesting less economic fallout from the pandemic. On the other hand, Nevada has ranked in the five states with the highest unemployment rates post-pandemic (2021 and 2022), suggesting perhaps a slower economic recovery due to COVID-19.

Case Study of Nevada: Misleading Overall Data

While a state’s overall unemployment rate may tell one story, a further breakdown into individual racial/ethnic subgroups may tell another, as we can see with Nevada.

Nevada’s total unemployment rate for 2021 was 7.2%, which was among the five states with the highest rate of unemployment for that year. However, the 2021 unemployment rate for White individuals in Nevada measured at 6.6% – lower than the overall state-level rate. In stark contrast, the 2021 unemployment rate for African American/Black individuals in Nevada measured at 15.3% – more than double the rates of White individuals in Nevada and the state’s overall unemployment rate.

Examining Unemployment Rate Trends by Race/Ethnicity

As observed in Nevada, a breakdown of unemployment rates by race/ethnicity gives insight to the disparities experienced by certain racial/ethnic subgroups. African American/Black, Hispanic, and Native American* individuals were more likely to suffer job loss compared to White workers during the pandemic. Adverse health outcomes and difficulty accessing healthcare are associated with longer periods of unemployment, which Black, Hispanic, and Native American workers endured more than White workers. Thus, it is important to consider the breakdown of race/ethnicity in relation to unemployment, especially when analyzing mid- and post-pandemic data.

While population-level unemployment rates may seem relatively low post-pandemic, a breakdown by race/ethnicity can reveal inequities and more detailed information regarding unemployment in the United States. The following chart shows the year-by-year total breakdown of unemployment by race/ethnicity, as well as the national rate for reference.

All four racial/ethnic groups follow the nationally observed unemployment trend: mid-pandemic (2020) rates are the highest, and, by 2022, unemployment had returned to pre-pandemic (2018 and 2019) levels.

However, deeper analyses of these five-year trends reveal disparities for certain racial/ethnic subgroups. For example, White individuals are the only racial/ethnic group to have their lowest national unemployment rate in the last five years be post-pandemic (3.2% in 2022). Compare that to African American/Black adults and Hispanic/Latino adults who, in the same year of 2022, have had higher unemployment rates (6.1% and 4.3%, respectively) than the national U.S. rate (3.6%). White and Asian adults have had lower unemployment than the U.S. rate for the last five years, except in 2020 where the unemployment rate for Asian adults was 8.7% compared to the U.S. rate of 8.1%.

Conclusion

Due to the implications that unemployment has on health and health care, it is important to consider the disparities in rates among different racial/ethnic groups. Even in states where unemployment may seem to be trending down, this rate could be misleading when not accounting for race/ethnicity.

Overall, national unemployment has returned to pre-pandemic rates, and the same trend has been observed across racial/ethnic groups. However, unemployment rates for African American/Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals are still consistently higher than the U.S. rate, revealing the need for targeted attention toward addressing unemployment rates for these populations.

To learn more about this and other related subjects, check out the following products on our site:

- Six Measures on SHADAC’s State Health Compare Now Updated to Include Pandemic-era Data for Health Behaviors and Outcomes

- Revised Childhood Vaccinations Measure on State Health Compare Shows Vaccination Rates Vary by State, Race/Ethnicity, and Insurance Coverage

- The Opioid Crisis in the Pandemic Era

You can also explore these and many other data measures with our State Health Compare tool here.

*State Health Compare does not currently have available data for Native American individuals, due to low response rate. However, SHADAC is hopeful this data gap will be addressed in the future in order to conduct equitable analyses.

Blog & News

2020 Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) Updates in the 2022 American Community Survey

March 26, 2024:A Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) is a type of geographic unit created for statistical purposes. PUMAs represent geographic areas with a population size of 100,000–200,000 within a state (PUMAs cannot cross state lines). PUMAs are the smallest level of geography available in American Community Survey (ACS) microdata. They are designed to protect respondent confidentiality while simultaneously allowing analysts to produce estimates for small geographic areas.

Every ten years, the decennial census results are used to redefine ACS PUMA boundaries to account for shifts in population and continue to maintain respondent confidentiality. This process is intended to yield geographic definitions that are meaningful to many stakeholders.

Most recently, new PUMAs were created based on the 2020 Census; these 2020 PUMAs were implemented in the ACS starting in the 2022 data year. Although Public Use Microdata Area components remain consistent to the extent possible, they are updated based on census results and revised criteria. Therefore, they are not directly comparable with PUMAs from any previous ACS data years. For example, the 2020 PUMAs used in the 2022 data year are distinct from the 2010 PUMAs, which were used in the 2012–2021 ACS data years.

The 2020 PUMAs were created based on definitions that include two substantive changes relative to the 2010 PUMAs:

1) An increase in the minimum population threshold for the minimum size of partial counties from 2,400 to 10,000. Increasing the population minimum for a PUMA-county part aims to further protect the confidentiality of respondents. However, exceptions are allowed on a case-by-case basis in order to maintain the stability of PUMA definitions (that were based on the previous minimum of 2,400) and due to unique geography.

2) Allowing noncontiguous geographic areas. Allowing PUMAs to include noncontiguous geographic areas aims to avoid unnecessarily splitting up demographic groups in order to provide more meaningful data. This change is not intended to create highly fragmented PUMAs.

Other than the two changes listed above, PUMA criteria remained consistent, such as treating 100,000 as a strict minimum population size for PUMAs. The maximum population size for PUMAs can exceed a population of 200,000 in certain instances due to expected population declines or geographic constraints.

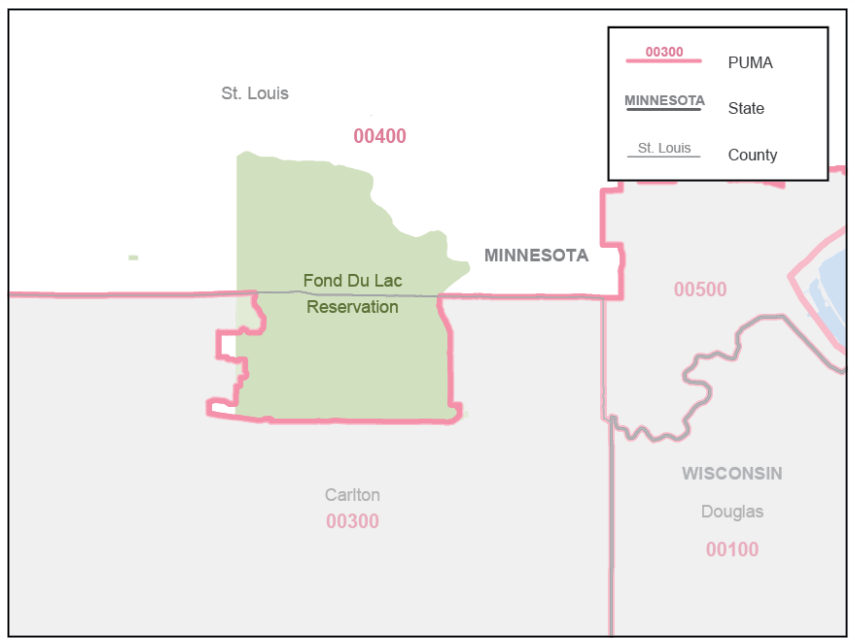

Generally, counties and census tracts are the building block geographies for PUMAs. This maximizes the stability of PUMA boundaries and therefore reduces disclosure risks. Counties may be combined or split as needed, depending on population size. Additionally, PUMAs are designed to avoid unnecessarily splitting metropolitan areas, minor civil divisions (MCDs) with a functional government, and areas of American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) and Native Hawaiian people. Carlton County in Minnesota, for example, illustrates that splitting a county was necessary to avoid splitting Fond du Lac reservation into multiple PUMAs (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022).

Figure 1: Minnesota PUMA 00400 Includes Fond du Lac Reservation in Its Entirety

Note: Minnesota PUMA 00400 featuring Fond Du Lac Reservation in its entirety. Reprinted from Final Criteria for Public Use Microdata Areas for the 2020 Census and the American Community Survey from https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/puma2020/2020PUMA_FinalCriteria.pdf.

Due to periodic changes in Public Use Microdata Area boundaries, states as a whole are the most granular geographic variable in the ACS microdata that can be compared consistently across all years. However, IPUMS USA offers harmonized geographic variables that greatly expand the options for analyzing ACS data across both time and geography. These variables are less granular than PUMAs, but more granular than states. For example, CONSPUMA and CPUMA0010 combine ACS PUMAs to create consistent geographies that can be compared across multiple decades of PUMA definitions; these have not yet been updated to include the new 2020 PUMAs. Currently, CITY, COUNTYFIP, and MET2013 allows users to compare cities, counties, and metropolitan areas, respectively, over years 2005-2022.

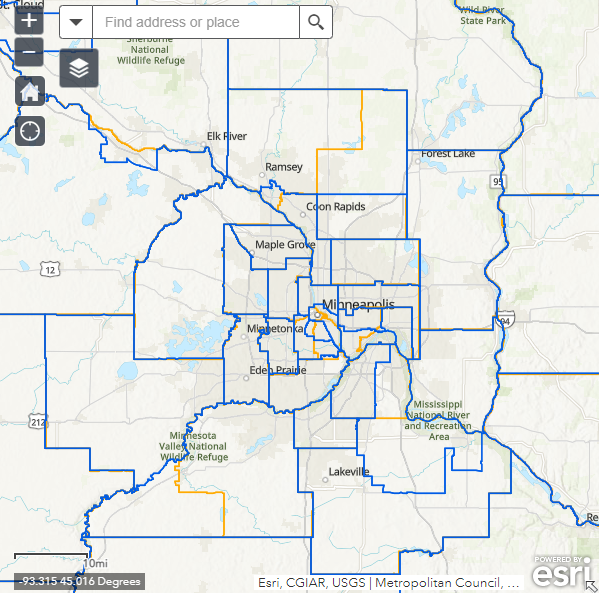

IPUMS USA also provides in-depth geographic resources for ACS data users, including interactive maps of the 2010 and 2020 PUMAs. For example, below is a map of the Twin Cities metropolitan area, Minnesota, showing 2020 PUMAs in blue and 2010 PUMAs in orange (IPUMS USA, 2020). This map illustrates that the updated PUMA criteria resulted in changes to PUMA boundaries in urban areas and some aggregation of PUMAs in more rural areas.

Figure 2: IPUMS USA Map of Twin Cities Metropolitan Area, Minnesota 2010 and 2020 PUMAs

Note: IPUMS USA Map of Twin Cities Metropolitan Area, Minnesota 2010 and 2020 PUMAs. Reprinted from 2020 PUMA DEFINITIONS: WEB MAP OF 2010 AND 2020 PUMAS from IPUMS USA, https://usa.ipums.org/usa/volii/pumas20.shtml.

Looking for other data and information from the American Community Survey? Learn more with the following SHADAC products:

2022 ACS Tables: State and County Uninsured Rates

American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHPI) data added to State Health Compare ACS estimates

Explore the Data on State Health Compare

Sources:

U.S. Census Bureau. (2022, July 25). Final Criteria for Public Use Microdata Areas for the 2020 Census and the American Community Survey. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/puma2020/2020PUMA_FinalCriteria.pdf

IPUMS USA (2020). 2020 PUMA Definitions: Web Map of 2010 and 2020 PUMAs. https://usa.ipums.org/usa/volii/pumas20.shtml.