Blog & News

Measuring State-level Disparities in Unhealthy Days (infographics)

January 2, 2022:Although health disparities in the United States have been common knowledge among public health professionals for years, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted this problem with vivid urgency. The disproportionate impact of the pandemic on certain segments of the population—such as higher infection and death rates among Black people and American Indian and Alaska Native people—isn’t an aberration but rather a consequence of systems that fail many communities. Health inequities run wide and deep in the U.S., extending far beyond COVID into other areas of physical and mental health.

Another issue the pandemic has highlighted is the enormous power that states have to influence health policy, as shown recently by mask and vaccination requirements instituted by some states—and prohibited by others. As the pandemic wanes, states will have a new opening to exercise their powers to tackle health inequities.

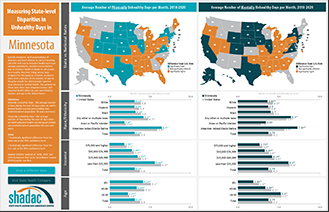

To help policymakers and other stakeholders identify opportunities to improve health equity in their states, SHADAC has produced a set of data resources for the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Survey—combining the three most recent years of data (2018-2020) to improve our ability to develop reliable state-level estimates for smaller population subgroups—we created both maps and charts that show how states compare to the U.S. average in measures of people’s self-reported physical and mental health, and how people’s physical and mental health varies depending on their race and ethnicity, level of income, and age within each state.

Click any state below to view its factsheet or click here to download a PDF of this blog and all state factsheets.

State physical and mental health

To assess how state residents’ physical and mental health matches up against the U.S. overall, SHADAC used statistical testing to compare the average number of days in the prior month that adults in each state report their physical or mental health was “not good” versus the average number for the same metric across the entire U.S.

Physical health

Among the states, 19 had an average number of physically unhealthy days that was better (i.e., lower) than the U.S. average of 3.8 days per month. Meanwhile, 20 states had an average number of physically unhealthy days that was worse (i.e., higher) than the U.S. average. The remaining 12 states had average numbers of physically unhealthy days that were not significantly different from the U.S. rate.

The District of Columbia reported the lowest average number of physically unhealthy days per month, at 3.0 days, while West Virginia reported the highest average number, at 5.5 days—a difference of two and a half extra days.

Mental health

For mental health, 17 states had an average number of unhealthy days that was better (i.e., lower) than the U.S. average of 4.2 days per month. Meanwhile, 19 states had an average number of mentally unhealthy days that was worse (i.e., higher) than the U.S. average. The remaining 15 states had average numbers of mentally unhealthy days that were not significantly different from the U.S. rate.

South Dakota reported the lowest average number of mentally unhealthy days per month, at 3.3 days, while West Virginia again reported the highest average number, at 5.7 days—a difference of almost two and a half extra days.

In addition to considering them separately, we also found substantial overlap in the states with mentally and physically unhealthy days that were significantly different from the U.S. average: 15 states had average numbers of unhealthy days that were better than the U.S. average for both physical and mental health, and 16 states had average numbers of unhealthy days that were worse than the U.S. average for both.

However, there were examples in which states demonstrated distinct differences. For instance, Utah and the District of Columbia both had physically healthy days that were significantly lower than the U.S. average, while their mentally unhealthy days were significantly higher than the U.S. average.

Physical and mental health inequities

While the dynamics vary state-to-state, physical and mental health data at the national level demonstrate clear inequities by demographics, including race and ethnicity, income, and age.

Race and ethnicity

Physical health

For the total U.S. population, the self-reported average of physically unhealthy days was 3.8 per month. This number varied across racial and ethnic population subgroups, with some clear health disparities—a finding that is consistent with other evidence of pervasive health inequities influenced by conditions such as discrimination and social risk factors, including lower incomes and limited access to health care.1

Asian and Pacific Islander people reported the lowest number of physically unhealthy days, at 2.0 days per month, which was significantly lower than the total population. Hispanic people also reported physically unhealthy days that were significantly lower than the total population, at 3.6 days per month.

American Indian and Alaska Native people reported the highest number of physically unhealthy days, at 5.9 days per month, which was significantly higher than the total population rate. Black people and White people reported average physically unhealthy days that were only slightly higher than the total population, at 3.9 days and 3.8 days per month, though those small differences were still significantly different.2 People reporting Any other race or multiple races also reported physically unhealthy days that were significantly higher than the total population, at 4.7 days per month.

Mental health

The pattern for mentally unhealthy days by race and ethnicity was similar to that for physically unhealthy days. For the total U.S. population, people reported an average of 4.2 mentally unhealthy days per month. Asian and Pacific Islander people reported the lowest number of mentally unhealthy days, at 2.8 days per month, which was significantly lower than the total population. Hispanic people also reported mentally unhealthy days that were significantly lower than the total population, at 4.0 days per month.

People reporting Any other race or multiple races reported the highest average number of mentally unhealthy days, at 5.9 days per month, which was significantly higher than the total population. American Indian and Alaska Native people reported the second-highest number of mentally unhealthy days, at 5.7 days per month, which again was significantly higher than the total population rate. Black people and White people reported average mentally unhealthy days that were only slightly higher than the total population, at 4.4 days and 4.3 days per month—seemingly small differences that were nevertheless statistically significant.

Income

Physical health

For the U.S. population, self-reported physical health was worse among people with lower incomes and better among people with higher incomes—an unsurprising finding, as income is associated with many factors related to health. For instance, people with lower incomes are more likely to live with poor air quality, as highways and industrial facilities that produce pollution tend to be found nearer to low-income housing.3,4 And people with higher incomes are more likely to have both health insurance and easier access to health care.5

People with incomes of $75,000 or more (the highest category in our analysis), reported the lowest average number of physically unhealthy days, at 2.1 per month. Furthermore, the average number of physically unhealthy days reported by individuals increased as their incomes decreased, with those in the $50,000 to $74,999 income category reporting 3.0 days per month. Both of those were significantly lower than the total U.S. population rate of 3.8 physically unhealthy days per month.

People with the lowest incomes (below $25,000), reported the highest average number of physically unhealthy days at 6.4 days per month—a figure roughly two and a half days higher than the total U.S. population and a statistically significant difference. Those with incomes between $25,000 and $49,999 reported 3.9 physically unhealthy days per month, which was just slightly higher than the total U.S. population number of 3.8 days, though the difference was still statistically significant.

Mental health

The overall pattern for self-reported mentally unhealthy days by income was almost identical to that for physically unhealthy days. People with the highest ($75,000 and higher) and next-highest ($50,000 to $74,999) incomes reported the lowest average mentally unhealthy days, at 3.0 and 3.8 days per month, respectively. Both were significantly lower than the average number of mentally unhealthy days for the U.S. population, at 4.2 per month.

People with the lowest incomes (less than $25,000) reported the highest number of mentally unhealthy days, at 6.3 days per month. That was roughly two additionally mentally unhealthy days compared to the total population average, a statistically significant difference. People with the next-lowest incomes ($25,000 to $49,999), reported an average of 4.5 mentally unhealthy days per month, which also was significantly higher than the total population average.

Age

Physical health

For the U.S. population, the number of self-reported physically unhealthy days increased along with age, a finding that is consistent with the fact that many common chronic health issues—such as heart disease and diabetes—are more prevalent among the older population.

Adults age 65 and over (“older adults”) reported the highest average number of physically unhealthy days, at 5.1 days per month, which was more than one day over the total U.S. population average of 3.8 days—a statistically significant difference. Adults age 40-64 (“middle-aged adults”) also reported an average number of physically unhealthy days that were significantly higher than the total U.S. population average, at 4.3 days per month. Meanwhile, adults age 18-39 (“younger adults”) reported the lowest average number of physically unhealthy days, at 2.4 days per month, which was almost two and a half fewer days than the total U.S. average—a statistically significant difference.

Mental health

In contrast with physically unhealthy days, the pattern for mentally unhealthy days by age was reversed: Average mentally unhealthy days declined as age increased. Though this pattern may be surprising to those unfamiliar with issues of mental health, it is consistent with other evidence, such as data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which finds that mental illness is roughly twice as common among adults 25 years and younger as compared to adults age 50 and older.6

Younger adults reported the highest average number of mentally unhealthy days per month, at 5.3 days. That number was roughly one day more than the total U.S. population rate of 4.2 days, a statistically significant difference. Meanwhile, older adults reported an average of 2.6 mentally unhealthy days per month, roughly one and a half fewer days than the overall U.S. population, and middle-aged adults reported an average of 4.1 mentally unhealthy days per month, which was only slightly lower than the overall population, but still a statistically significant difference.

Conclusion

Understanding how individuals’ self-reported mental and physical health vary across the states and by subpopulation at the national level offers one approach to identifying broad health inequities. Comparing the average number of physically and mentally unhealthy days for state residents against the U.S. average can allow states to identify widespread gaps. And within their populations, those same data offer states an opportunity to identify more specific health inequities. At the U.S. level, data show that certain demographic groups experience worse health. For instance, American Indian and Alaska Native people on average report significantly worse mental and physical health, as do people with lower incomes. Meanwhile, younger adults report significantly worse mental health, while older adults report significantly worse physical health. The state-level data SHADAC has published in this resource provides states with an ability to examine health inequities for their particular populations.

Click here to download this blog, data tables, and all state factsheets.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (December 2020). Introduction to COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/racial-ethnic-disparities/index.html

2 With rounding, the difference between the average number of physically unhealthy days for White people versus the total population isn’t apparent; however, it is just under 0.1 days (3.75 for the U.S. total, 3.84 for White people).

3 Finkelstein, M.M., Jerrett, M., DeLuca, P., Finkelstein, N., Verma, D.K., Chapman, K., & Sears, M.R., (2003, September 2). Relation between income, air pollution and mortality: A cohort study. CMAJ JAMC, 169(5), 397-402. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC183288/

4 Pratt, G.C., Vadali, M.L., Kvale, D.L., & Ellickson, K.M. (May 2015). Traffic, air pollution, minority and socio-economic status: Addressing inequities in exposure and risk. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 12(5), 5355-5372. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4454972/

5 State Health Compare. (n.d.). State Health Compare. State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC). http://statehealthcompare.shadac.org/

6 National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). (n.d.). Mental illness. National Institute of Health (NIH). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness

Publication

COVID-19 illness personally affected nearly 97 million U.S. adults

New brief shows results from SHADAC COVID-19 Survey on population experiences with COVID sickness and death

Researchers at SHADAC have fielded an updated version of the SHADAC COVID-19 Survey in April 2021, aimed at understanding respondents’ experiences with illness and death due to COVID-19 for themselves, their families, and their contacts.

Results from the survey, presented in the brief to the right, showed that almost 40% of adults in the U.S.:

- Know someone who has died from COVID.

Among the adults surveyed, 37.7 percent responded that they know someone who died from the coronavirus. By race/ethnicity, roughly half of Black (56.9 percent) and Hispanic (48.2 percent) adults reported knowing someone who died of COVID-19, a significantly higher amount than White adults or those who reported as “any other” or multiple races. Other breakdowns for this question included age, income level, and education level, for which adults reported similar rates to the overall total (37.7 percent), for knowing someone who died from the coronavirus.

- Either themselves have, or had a family member who has, contracted COVID.

Among the adults surveyed, 37.6 percent responded that either they or a family member had become ill due to COVID. Notable breakdowns included about half of Hispanic adults (51.5 percent) who reported that they or an immediate family member had COVID-19, and adults with some college or associate’s degree (44.0 percent) were also more likely to report that they or an immediate family member had COVID-19. Among other categories of age and income level, significantly different percentages from the overall total (37.6 percent) were not seen.

More on the survey

The SHADAC COVID-19 Survey on the impacts of the pandemic on respondents’ experiences with COVID-related illness and death was conducted as part of the AmeriSpeak Omnibus Survey conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago. The survey was conducted using a mix of phone and online modes in April 2021 among a nationally representative sample of 1,007 respondents age 18 and older.

This survey is a continuation of the initial SHADAC COVID-19 Survey, which was aimed at understanding the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on health care access and insurance coverage and pandemic-related stress, and was conducted as part of the same survey, by the same agency, during a similar time frame (April 24-26, 2020), using the same methods, and a similar population sample.

Results from the first iteration of the survey are available in separate briefs on health insurance coverage and access to care and pandemic-related stress, as well as in a pair of chartbooks.

Blog & News

(Webinar) U.S. Health On the Rocks: The Quiet Threat of Growing Alcohol Deaths

August 01, 2024:Date: Tuesday, September 21st

Time: 3:00 PM Central / 4:00 PM Eastern

While much public attention has been given to the opioid epidemic, the United States has been quietly experiencing another growing public health crisis that surpasses opioid overdoses as a cause of substance abuse-related deaths in nearly half of all states: alcohol-involved deaths.

Using data from a recent analysis of alcohol-involved deaths from 2006 to 2019, SHADAC will host a webinar on Tuesday, September 21st detailing the trends in rising alcohol-involved deaths across the U.S., among the states, and for certain demographic groups.

Speakers

Carrie Au-Yeung, MPH, SHADAC – Ms. Au-Yeung will speak about variation in alcohol-related death rates across the states, as well as provide comparisons to opioid-related death rates in order to better understand the scale and context of substance use issues among the states.

Colin Planalp, MPA, SHADAC – Mr. Planalp will talk about national-level increases in alcohol death rates as well as rising rates for demographic groups by race and ethnicity, age, gender and urbanization.

Tyler Winkelman, MD, MSc, Hennepin Healthcare – Dr. Winkelman will discuss how the data serve can help us understand the impacts of the pandemic on alcohol-involved disease and deaths as well as the case for expanding our response to substance use issues beyond opioids.

A question and answer session will be open for all attendees following the webinar presentation. Attendees are encouraged to submit questions for any or all of the speakers prior to the webinar, and can do so here.

Slides from the webinar are available for download.

Resources

Escalating Alcohol-Involved Death Rates: Trends and Variation across the Nation and in the States from 2006 to 2019 (Infographics)

U.S. Alcohol-Related Deaths Grew Nearly 50% in Two Decades: SHADAC Briefs Examine the Numbers among Subgroups and States (Blog)

Pandemic drinking may exacerbate upward-trending alcohol deaths (Blog)

BRFSS Spotlight Series: Adult Binge Drinking Rates in the United States (Infographic)

Blog & News

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey

July 19, 2021:Update 6: June 9 to June 21

The COVID-19 vaccines promise to help protect individual Americans against infection and eventually provide population-level herd immunity. After several months of rolling out the various one and two-shot COVID-19 vaccines, which have included hiccups from the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, vaccination rates continue to increase at a slow but steady pace. Although the country fell short of meeting the current administration’s goal of vaccinating 70% of the adult population by July 4 (as measured by official administrative data reported to the Centers for Disease Control [CDC]), several states have achieved this goal.

Over the past several months, all states have increased COVID-19 vaccine rollout by expanding vaccine access to the general adult population and children over 12. However, there are still concerns on prioritization decisions and the existing mechanisms of the vaccine rollout—in addition to evidence that lower-income individuals, people of color, and individuals without strong connections to the health care system are less likely to get vaccinated—which have created challenges in equitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine and could worsen existing pandemic-related health inequities.

The available data have not assuaged these concerns, and show patterns of lower vaccination rates among people with lower levels of education, no health insurance coverage, and marginalized racial and ethnic groups. The U.S. Census Bureau recently released updated data on take-up of COVID-19 vaccines from its Household Pulse Survey (HPS), collected June 9-21, 2021. The HPS is an ongoing, biweekly tracking survey designed to measure impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. These data provide an updated snapshot of COVID-19 vaccination rates and are the only data source to do so at the state level by subpopulation.

This blog post presents top-level findings from these new data, focusing on rates of vaccination (one or more doses) among U.S. adults (age 18 and older) living in households and comparing to results from the last half of March, the most recent time period of comparison from this ongoing blog series.

These data represent the latest release from Phase 3.1 of the HPS, which has a biweekly data collection and dissemination approach. The Census Bureau has indicated that it plans to continue administering the survey through December 2021.

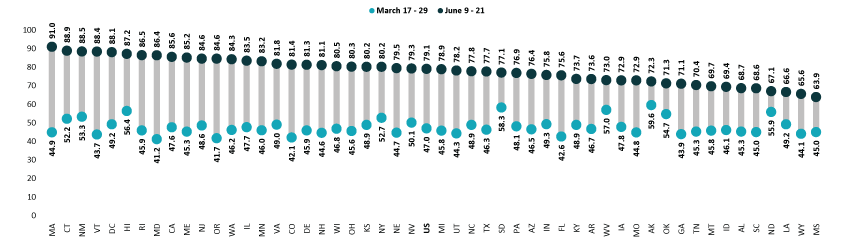

Nationally, over three-fourths of adults had received a vaccination, but this varied by state

According to the new HPS data, 79.1% of U.S. adults had received one or more COVID-19 vaccinations towards the end of June1, though this varied by state from a low of 63.9% in Mississippi to a high of 91.0% in Massachusetts. At least four in five adults had received a vaccine in 22 states and the District of Columbia.

Vaccination rates increased considerably across all states; states with lower rates catching up

Nationally, adult vaccination rates substantially increased from the last half of March, rising from 47.0% during March 17-29, 2021, to 79.1% during June 9-21, 2021. Many states experienced large increases in their vaccination rates. The size of these increases varied from an 11.2 percentage-point (PP) increase in North Dakota to a 46.1 PP increase in Massachusetts. Five states saw increases of 40.0 PP or larger: Maryland, Massachusetts, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine, 2021

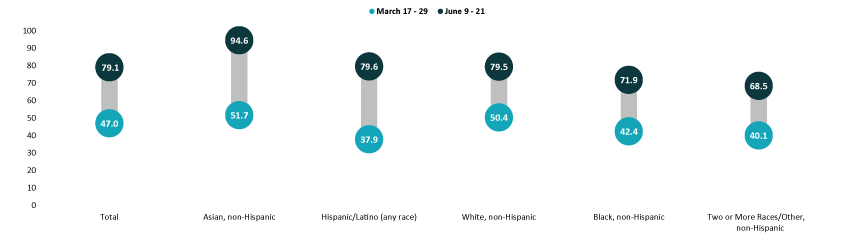

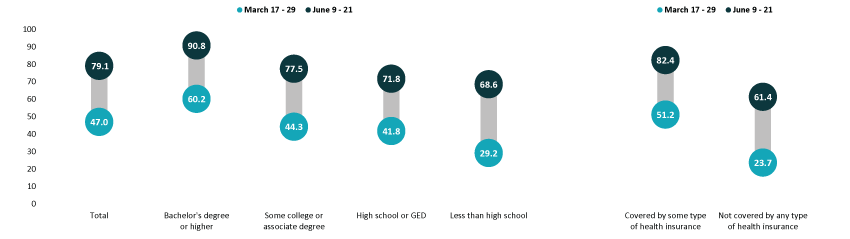

Disparities in vaccination rates improved, but slowly and unevenly

Although there have been ongoing strategies to achieve health equity in COVID-19 vaccine rollouts, vaccination rates continued to vary to a great degree by demographic and socioeconomic factors. Gaps in vaccination compared to the national average narrowed slightly for most groups, though some saw larger improvements. As with previous iterations in this blog series, vaccination rates were lower for certain subpopulations such as Black adults, adults who identified as “Some other race/Multiple races,” adults without a high school education, and adults without health insurance coverage. More resources, attention, or new strategies may be needed to close the gaps for these hardest-to-reach groups.

Asian and White adults continued to have above-average vaccination rates at 94.6% and 79.5%, respectively. Rates among Black adults (71.9%) and adults identifying with “Two or more” (Multiple) or “Some other” race (68.5%) continued to be below the national average. Rates among Hispanic/Latino adults improved, and are now above the national average at 79.6%. Hispanic/Latino adults also saw the largest improvement relative to the national average, going from almost 20 percent below the national average in late March (37.9% vs. 47.0%) to nearly one percent above the national average in June (79.6% vs. 79.1%).

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine by Race/Ethnicity, 2021

Disparities by education level remained, with adults holding a bachelor’s degree or higher continuing to have the highest vaccination rate at 90.8%, and adults without a high school diploma having the lowest vaccination rate at 68.6%. Despite having the lowest vaccination rate, adults without a high school diploma had the largest relative improvement to the national average, going from 38 percent below the national average in March (29.2% vs. 47.0%) to 13 percent below the national average in June (68.6% vs. 79.1%). Vaccination rates among adults with a high school degree or equivalent and adults with some college or an associate’s degree also improved somewhat relative to the national average.

Adults with health insurance coverage had an above-average vaccination rate at 82.4%, while uninsured adults had a below-average vaccination rate at 61.4%. Regardless of having a rate substantially below the average, the rate among those not covered by any type of health insurance had a notable improvement relative to the national average, going from 50 percent below the national average in March (23.7% vs. 47.0%) to 22 percent below the national average in June (61.4% vs. 79.1%).

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine by Education and Health Insurance Status, 2021

Notes about the Household Pulse Survey Data

The estimated rates presented in this post were pulled from the HPS COVID-19 Vaccination Tracker published by the Census Bureau. Though these counts are accompanied by standard errors, standard errors are not able to be accurately calculated for rate estimates. Therefore, we are not able to determine if the differences we found in our analysis are statistically significant or if the estimates themselves are statistically reliable. Estimates and differences for subpopulations at the state level should be assumed to have large confidence intervals around them and caution should be taken when drawing strong conclusions from this analysis. However, the fact that these indications of COVID-19 inequities mirror patterns of other vaccinations inequities demonstrate reason for concern.

Though produced by the U.S. Census Bureau, the HPS is considered an “experimental” survey and does not necessarily meet the Census Bureau’s high standards for data quality and statistical reliability. For example, the survey has relatively low response rates (6.4% for June 9-21), and sampled individuals are contacted via email and text message, asking them to complete an internet-based survey. These issues in particular could be potential sources of bias, but come with the tradeoffs of increased speed and flexibility in data collection as well as lower costs. A future post will investigate differences between COVID-19 vaccination rates estimated from survey data (such as the HPS) and administrative sources. The estimates presented this post are based on responses from 68,067 adults. More information about the data and methods for the Household Pulse Survey can be found in a previous SHADAC blog post.

Previous Blogs in the Series

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Analysis of the Household Pulse Survey (Update 5: March 17 to March 29) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Analysis of the Household Pulse Survey (Update 4: March 3 to March 15) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update 3: Feb 17 to March 1) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update 2: Feb 3 to Feb 15) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update: Jan 10 to Feb 1) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: New State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Jan 6 to Jan 18) (SHADAC Blog)

Related Reading

Vaccine Hesitancy Decreased During the First Three Months of the Year: New Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (SHADAC Blog)

State-level Flu Vaccination Rates among Key Population Subgroups (50-state profiles) (SHADAC Infographics)

50-State Infographics: A State-level Look at Flu Vaccination Rates among Key Population Subgroups (SHADAC Blog)

Anticipating COVID-19 Vaccination Challenges through Flu Vaccination Patterns (SHADAC Brief)

New Brief Examines Flu Vaccine Patterns as a Proxy for COVID – Anticipating and Addressing Coronavirus Vaccination Campaign Challenges at the National and State Level (SHADAC Blog)

Ensuring Equity: State Strategies for Monitoring COVID-19 Vaccination Rates by Race and Other Priority Populations (Expert Perspective for State Health & Value Strategies)

SHADAC Webinar - Anticipating COVID-19 Vaccination Challenges through Flu Vaccination Patterns (February 4th) (SHADAC Webinar)

1 Note that it is not unusual for there to be appreciable differences between survey-based estimates and those derived from administrative data, as there are here between the vaccination rates observed in the HPS and those seen in CDC administrative vaccination data. There could be several reasons for these differences, including differences in the population universe (i.e., household-residing adults vs. total adult population), differences in the measured time period, the inaccuracies between self-reported vs. administratively collected data, and differences in the representativeness of survey vs. administrative data. Although administrative data are often thought to be more accurate than survey-based estimates, survey data such as the HPS have the advantage of providing more granular detail about the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of populations of interest that are often unavailable or incomplete in administrative data.

Blog & News

Drug overdose deaths grew by almost 30 percent in 2020

July 15, 2021:Fentanyl- and methamphetamine-type drugs surged roughly 50 percent in 2020

Drug overdose deaths surged in the United States during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing nearly 30 percent in just 12 months. Provisional data recently published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that more than 92,000 people died of drug overdoses in 2020—surpassing records yet again.1

The growth was widespread throughout the country, with only two states (New Hampshire and South Dakota) spared from the jump in drug overdose deaths. Conversely, some states saw their death rates increase more than 50 percent, including Kentucky, South Carolina, Vermont, and West Virginia.

Much of the growth in drug overdose deaths was driven by synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, which increased more than 50 percent from 2019 to 2020 (see Figure 1). Fentanyl has become a key product for international drug traffickers, often finding its way as an adulterant in other drugs like heroin and cocaine, and even as an ingredient in counterfeits of common opioid prescription pills such as Oxycontin. The emergence of fentanyl in the U.S. illicit drug trade is a newer phenomenon beginning in the past decade, and it has recently spread from eastern states to increasingly affect states in the western half of the country as well.

Figure 1. Changes in drug overdose deaths in the U.S., 2019 to 2020

A family of drugs called “psychostimulants”—mostly methamphetamine—also drove a large increase in deaths in 2020, up nearly 50 percent since 2019. Deaths involving methamphetamine and other psychostimulants have grown dramatically in the past few years. The increased death toll involving psychostimulants is likely caused by two factors: First, the methamphetamine trafficked in the U.S. today is generally much more potent than methamphetamine sold in the past, raising the potential risk of overdoses caused by methamphetamine. Second, methamphetamine today is often contaminated with, or used alongside, synthetic opioids, raising the risk of an overdose involving the use of multiple drugs simultaneously.

Of the main drugs involved in overdoses2, only heroin was associated with a decline in deaths during 2020—falling by less than 10 percent since 2019. Meanwhile, overdose deaths involving prescription opioids increased more than 20 percent, reversing a trend of relatively stable or even declining death rates over several years. Cocaine overdose deaths similarly increased by more than 20 percent in 2020.

1 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). (2021, July 14). Vital Statistics Rapid Release: Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts [Data set]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

2 The drug overdose death categories presented in the CDC data include: heroin, natural opioid analgesics (e.g., morphine and codeine) and semisynthetic opioids (e.g., oxycodone and hydrocodone), synthetic opioids such as methadone and synthetic opioids other than methadone (e.g., fentanyl and tramadol), cocaine, and psychostimulants.