Blog & News

State Health Compare Adds New Social Determinants Measure: Percent of Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences

September 14, 2020:A new State Health Compare measure examines the prevalence and degree of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among different demographic groups, with estimates available across the states and over time.

What are ACEs?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines ACEs as “potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years)” including experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect; witnessing violence in the home or community; or having a family member attempt or die by suicide. ACEs also include “aspects of the child’s environment that can undermine their sense

of safety, stability, and bonding,” such growing up in a household with substance misuse, mental health problems, and instability due to parental separation or household members being in jail or prison.i

Why are ACEs Important?

A landmark study conducted in the 1990s found a significant relationship between the number of ACEs an individual experienced and a variety of negative outcomes in adulthood, including poor physical and mental health, substance abuse, and risky behaviors (e.g., smoking, having a history of sexually transmitted disease/infection, etc.). The more ACEs an individual experienced, the greater the risk of these outcomes.ii Because ACEs are common, with about 61% of adults reporting at least one type of ACE and nearly one in six reporting four or more types of ACEs, preventing ACEs

could reduce a large number of negative physical and behavioral health outcomes.iii

How Can We Prevent ACEs?

Creating and sustaining safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments for children and families can prevent ACEs.iv Data on the prevalence and severity of ACEs among different groups can help policymakers and public health professionals target prevention efforts effectively so that resources are efficiently leveraged to support these relationships and environments where they are most needed.

What Can We Learn from the State Health Compare Estimates?

The ACEs estimates presented in State Health Compare indicate the percent of children with no ACEs, the percent of children with one ACE, and the percent of children with multiple ACEs. Breakdowns are available by age, insurance coverage type, education, poverty level, and race/ethnicity. Available time periods are the two-year pooled periods of 2016-2017 and 2017-2018

Children with ACEs: Data Highlights

Nationwide, an estimated 18.6% of all children (age 0-17) had multiple ACEs in 2017-2018, 23.3% had one ACE, and 58.2% had zero ACEs. The following section takes a quick dive into the percentages of children with multiple ACEs to highlight some of the subgroup analyses that are available using State Health Compare.

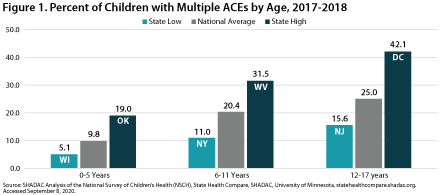

Percent of Children with Multiple ACEs: By Age Group

Figure 1 shows the national rates of children with multiple ACEs and state high and low rates for different age groups of children, with rates tending to be higher among older children and lower among younger children. Overall, the lowest percentage of children with multiple ACEs by age was 5.1% among 0-5 year-olds in Wisconsin, and the highest percentage was 42.1% among 12-17 year-olds in the District of Columbia (DC).

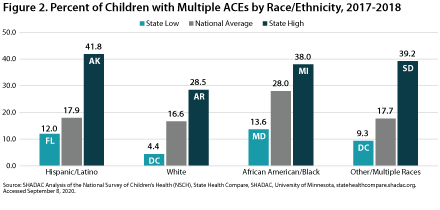

Percent of Children with Multiple ACEs: By Race/Ethnicity

Figure 2 shows the national rates and state high and low rates for children with multiple ACEs by race/ethnicity in 2017-2018. When examining the national rate of children with multiple ACEs by race/ethnicity, as well as state-level highs and lows for this measure, White children consistently ranked at the bottom, with the lowest percentage being 4.4% among White children living in DC. The highest nation- wide percentage of children with multiple ACEs by race/ethnicity was among African American/Black children, of whom 28% had more than one ACE. The highest state-level percentage was 41.8% among Hispanic/Latino children living in Alaska.

Figure 2 shows the national rates and state high and low rates for children with multiple ACEs by race/ethnicity in 2017-2018. When examining the national rate of children with multiple ACEs by race/ethnicity, as well as state-level highs and lows for this measure, White children consistently ranked at the bottom, with the lowest percentage being 4.4% among White children living in DC. The highest nation- wide percentage of children with multiple ACEs by race/ethnicity was among African American/Black children, of whom 28% had more than one ACE. The highest state-level percentage was 41.8% among Hispanic/Latino children living in Alaska.

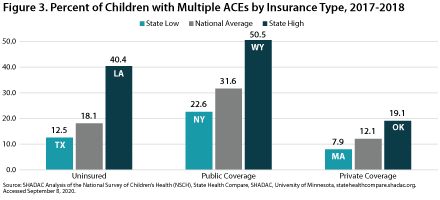

Percent of Children with Multiple ACEs: By Insurance Coverage Type

Figure 3 shows the percentage of children with two or more ACEs according to insurance status in 2017-2018. Nationwide, the highest proportion of children reporting multiple ACEs was among those with public coverage, at 31.6 percent. This is more than 2.5 times the nationwide low of 12.1 percent among children with private coverage. At the state level, a low of 7.9 percent of privately insured children in Massachusetts reported multiple ACEs, versus a high of 50.5 percent of publicly insured children in Wyoming.

Figure 3 shows the percentage of children with two or more ACEs according to insurance status in 2017-2018. Nationwide, the highest proportion of children reporting multiple ACEs was among those with public coverage, at 31.6 percent. This is more than 2.5 times the nationwide low of 12.1 percent among children with private coverage. At the state level, a low of 7.9 percent of privately insured children in Massachusetts reported multiple ACEs, versus a high of 50.5 percent of publicly insured children in Wyoming.

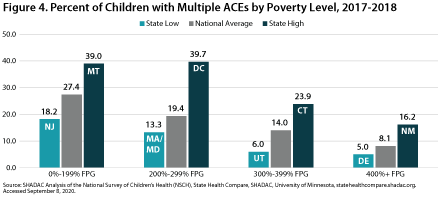

Percent of Children with Multiple ACEs: By Poverty Level

Figure 4 shows the prevalence of multiple ACEs by poverty level in 2017-2018. The national percentage of children who had multiple ACEs by poverty level was highest among children at 0 to 199 FPG at 27.4 percent. This proportion was lowest among children in household with incomes at or above 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Guideline (FPG) at 8.1 percent—a 19.3 percentage-point difference from the rate for high-income children. At the state level, the highest percentages of children with multiple ACES by poverty level were 39.7 percent among children at 200 to 299 percent FPG living in DC and 39.0 percent among children at 0 to 199 percent FPG living in Montana. The state low for multiple

Figure 4 shows the prevalence of multiple ACEs by poverty level in 2017-2018. The national percentage of children who had multiple ACEs by poverty level was highest among children at 0 to 199 FPG at 27.4 percent. This proportion was lowest among children in household with incomes at or above 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Guideline (FPG) at 8.1 percent—a 19.3 percentage-point difference from the rate for high-income children. At the state level, the highest percentages of children with multiple ACES by poverty level were 39.7 percent among children at 200 to 299 percent FPG living in DC and 39.0 percent among children at 0 to 199 percent FPG living in Montana. The state low for multiple

ACEs by poverty level was 5.0 percent among children at

or above 400 percent FPG living in Delaware.

Learn More

To explore State Health Compare’s ACEs estimates further, visit State Health Compare at statehealthcompare.shadac.org and click on “Explore Data.”

Other social and economic factors that can be explored through State Health Compare include:

i Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (April 2020). “Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences.” Available at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/fastfact.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fviolenceprevention%2Fchildabuseandneglect%2Faces%2Ffastfact.html

ii Felitti, V.J., Anda, R.F., Nordenberg, D., Edwards, B.A., Koss, M.P., Marks, J.S. (May 1998). “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14(4): 245-258. DOI: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8.

iii Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (April 2020). “Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences.” Available at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/fastfact.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fviolenceprevention%2Fchildabuseandneglect%2Faces%2Ffastfact.html

iv Ibid.

Blog & News

After drop in 2018, newer data indicate a resurgence in drug overdose deaths

August 26, 2020:While new SHADAC research found small but statistically significant declines in opioid and drug overdose death rates during 2018, newer data indicate those reductions may have been short-lived. Overall, in 2018, drug overdose death rates declined 4.6 percent as compared to the prior year, but our analysis also found variation in amounts and direction of changes in individual types of drugs. For instance, overdose death rates from prescription opioids dropped 14.7 percent and those from heroin dropped 3.8 percent, but overdose death rates from synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl) increased 9.6 percent and those from psychostimulants (e.g., methamphetamine) grew 22.1 percent.

Provisional data published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show evidence of an increase in overall drug overdose deaths in 2019, as well as for certain individual types of drugs. During a rolling 12-month period ending in December 2019, drug overdose deaths reached a record high of 70,980—a 4.6 percent increase over the 12-month period ending in December 2018.1 And among the states, 36 of 50 saw increases in their reported drug overdose deaths. In that same amount of time, overdose deaths from synthetic opioids increased 15.8 percent and overdose deaths from psychostimulants increased 26.8 percent.

The state of Minnesota also recently published its own preliminary data on drug overdose deaths in 2019, finding similar patterns to the U.S. After experiencing a decline in drug overdose deaths in 2018, Minnesota reported that preliminary data showed a 20 percent increase in overall drug overdoses in 2019—in addition to synthetic opioid overdose deaths that increased by 48 percent, and psychostimulant overdose deaths that grew by 37 percent.2

Some reports also indicate that drug overdose deaths may have spiked in early 2020, coinciding with the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic and various associated stressors. For example, a White House analysis found an 11.4 percent increase in overdose deaths in the first four months of 2020 as compared to the prior year.3 In the midst of the COVID-19 emergency, experts such as those from the National Academy of Medicine have raised concerns that “the nation is experiencing an unprecedented convergence of epidemics, and there is great concern that the opioid crisis…may only worsen in the absence of a concerted response.”4

As new data on drug overdoses become available in the coming months and years, it will be vital to monitor the continually shifting dynamics of the opioid crisis, to identify early the emerging patterns—such as the rise of synthetic opioids and psychostimulants—and to continue to guide policy efforts to address the persistent public health emergencies of substance use and drug overdose deaths.

Explore SHADAC's most recent analysis of the Widening Drug Overdose Crisis in the United States or visit our Opioid Epidemic Resources page to access all opioid-related analysis done by SHADAC researchers over the last several years.

1 Ahmad, F.B., Rossen L.M., & Sutton, P. (2020). Provisional drug overdose death counts [National Center for Health Statistics report]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

2 DeLaquil, M., Giesel, S., & Wright, N. (n.d.). Preliminary 2019 drug overdose deaths: A return to the states’ overall trend [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/opioids/documents/2019prelimdeathreport.pdf

3 Ehley, B. (2020, July 2). Pandemic unleashes a spike in overdose deaths. Politico. Retrieved from https://www.politico.com/news/2020/06/29/pandemic-unleashes-a-spike-in-overdose-deaths-345183

4 National Academy of Medicine. (2020). Mapping our impacts. Available from https://nam.edu/programs/action-collaborative-on-countering-the-u-s-opioid-epidemic/mapping-our-impact/

Publication

Overdose Crisis in Transition: Changing National and State Trends in a Widening Drug Death Epidemic

For nearly two decades, the United States has experienced a growing and evolving crisis of substance abuse and addiction; a crisis illustrated by statistically significant increases in overdose deaths directly from, or related to, opioids. These increases have occurred throughout the country, as the annual number of drug overdose deaths has nearly quadrupled from 17,500 in 2000 to 67,400 in 2018, and nearly every state has experienced increases in overdose deaths from one or more types of opioids since 2000.1,2

In the years since the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared overdoses from prescription painkillers an “epidemic” in 2011, the opioid overdose crisis has evolved rapidly from a problem tied mostly to prescription opioid painkillers to one driven by illicitly trafficked heroin, to one marked by the rise of synthetic opioids, to most recently one with surging numbers of overdose deaths related to cocaine and psychostimulants—non-opioid illicit substances that have been linked to the opioid crisis via emerging evidence from both the CDC and U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).3,4

Variations in the opioid and opioid-related drug overdose crisis have become especially pronounced in recent years. While data from the CDC has shown that drug overdose deaths overall and opioid overdose deaths in aggregate declined a small but statistically significant amount from 2017 to 2018 (4.6 percent), examining data at a more granular level shows a more nuanced picture. While deaths from prescription opioids and heroin declined in 2018, deaths from synthetic opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants increased significantly to reach new record highs.

As a result of these more current variations, SHADAC’s annually produced opioid and opioid-related drug overdose briefs have shifted slightly in order to particularly focus on changes in overdose deaths across the nation and among the states in more recent years, especially in 2018. The briefs provide high-level information about opioids and opioid addiction, present the historical context for the epidemic of opioid and related addiction and mortality in the United States, and examine trends in opioid-related mortality across the country and among population subgroups between 2017 and 2018.

Related Resources

The Opioid Epidemic in the United States

50-State Analysis of Drug Overdose Trends: The Evolving Opioid Crisis Across the States (Infographics)

After drop in 2018, newer data indicate a resurgence in drug overdose deaths (Blog)

The Evolving Opioid Epidemic: Observing the Changes in the Opioid Crisis through State-level Data (Webinar)

The Opioid Epidemic: National and State Trends in Opioid-Related Overdose Deaths from 2000 to 2017 (Briefs)

1 Hedegaard, H., Miniño, A.M., & Warner, M. (2020). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2018 [Data brief No. 356]. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db356-h.pdf

2 State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC). (2019). The opioid epidemic: State trends in opioid-related overdose deaths from 2000 to 2017 [PDF file]. Available from http://www.shadac.org/2017OpioidBriefs

3 Kariisa, M., Scholl, L., Wilson, N., Seth, P., & Hoots, B. (2019, May 3). Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential—United States, 2003-2017. MMWR, 68(17), 388-395. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6817a3

4 Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Strategic Intelligence Section. (2020). 2019 National Drug Threat Assessment [DEA-DCT-DIR-007-20]. Retrieved from https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01/2019-NDTA-final-01-14-2020_Low_Web-DIR-007-20_2019.pdf

Blog & News

90 percent of U.S. adults report increased stress due to pandemic

May 26, 2020:Colin Planalp, MPA, Giovann Alarcon, MPP, Lynn A. Blewett, PhD,

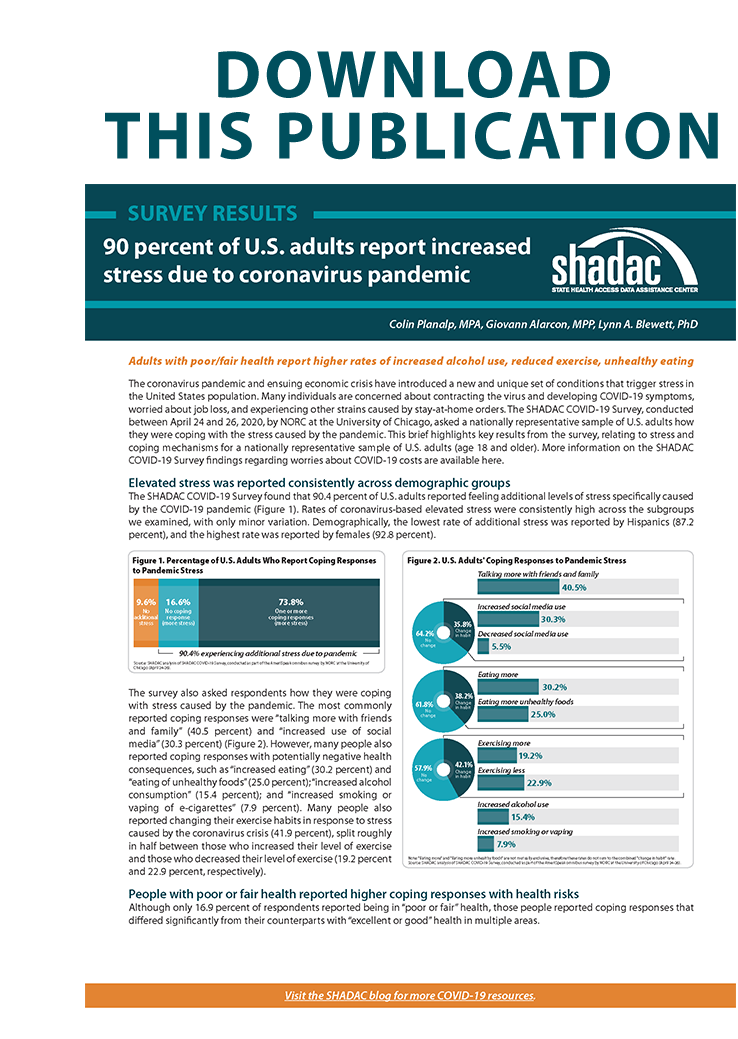

The coronavirus pandemic and ensuing economic crisis have introduced a new and unique set of conditions that trigger stress in the United States population. Many individuals are concerned about contracting the virus and developing COVID-19 symptoms, worried about job loss, and experiencing other strains caused by stay-at-home orders. The SHADAC COVID-19 Survey, conducted between April 24 and 26, 2020, by NORC at the University of Chicago, asked a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults how they were coping with the stress caused by the pandemic. This brief highlights key results from the survey, relating to stress and coping mechanisms for a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults (age 18 and older). More information on the SHADAC COVID-19 Survey findings regarding worries about COVID-19 costs are available here.

Elevated stress was reported consistently across demographic groups

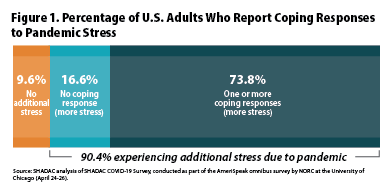

The SHADAC COVID-19 Survey found that 90.4 percent of U.S. adults reported feeling additional levels of stress specifically caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1). Rates of coronavirus-based elevated stress were consistently high across the subgroups we examined, with only minor variation. Demographically, the lowest rate of additional stress was reported by Hispanics (87.2 percent), and the highest rate was reported by females (92.8 percent).

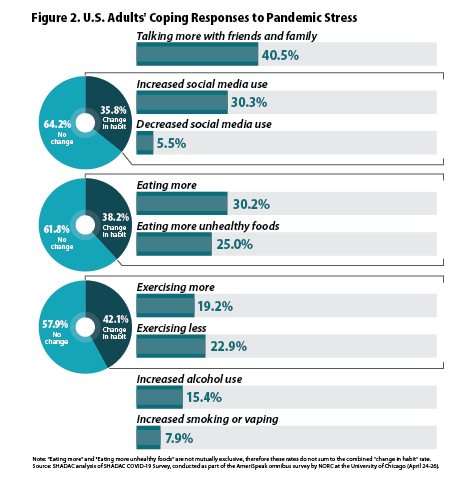

The survey also asked respondents how they were coping with stress caused by the pandemic. The most commonly reported coping responses were “talking more with friends and family” (40.5 percent) and “increased use of social media” (30.3 percent) (Figure 2). However, many people also reported coping responses with potentially negative health consequences, such as “increased eating” (30.2 percent) and “eating of unhealthy foods” (25.0 percent); “increased alcohol consumption” (15.4 percent); and “increased smoking or vaping of e-cigarettes” (7.9 percent). Many people also reported changing their exercise habits in response to stress caused by the coronavirus crisis (41.9 percent), split roughly in half between those who increased their level of exercise and those who decreased their level of exercise (19.2 percent and 22.9 percent, respectively).

The survey also asked respondents how they were coping with stress caused by the pandemic. The most commonly reported coping responses were “talking more with friends and family” (40.5 percent) and “increased use of social media” (30.3 percent) (Figure 2). However, many people also reported coping responses with potentially negative health consequences, such as “increased eating” (30.2 percent) and “eating of unhealthy foods” (25.0 percent); “increased alcohol consumption” (15.4 percent); and “increased smoking or vaping of e-cigarettes” (7.9 percent). Many people also reported changing their exercise habits in response to stress caused by the coronavirus crisis (41.9 percent), split roughly in half between those who increased their level of exercise and those who decreased their level of exercise (19.2 percent and 22.9 percent, respectively).

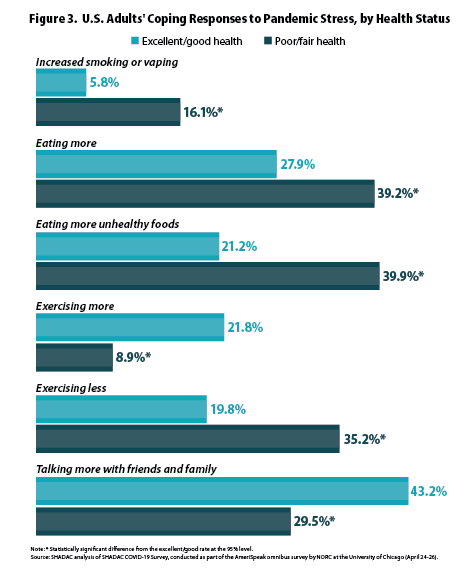

People with poor or fair health reported higher coping responses with health risks

Although only 16.9 percent of respondents reported being in “poor or fair” health, those people reported coping responses that differed significantly from their counterparts with “excellent or good” health in multiple areas.

Increased smoking or vaping

People with poor/fair health reported increased smoking or vaping at rates almost triple those of people with excellent/good health (16.1 percent vs. 5.8 percent), which was a statistically significant difference (Figure 3).

Eating more and eating unhealthy foods

People with poor/fair health reported increased consumption of unhealthy foods at almost double the rate of people with excellent/good health (39.9 percent vs. 21.2 percent), while also reporting higher rates of increased eating (39.2 percent vs. 27.9 percent)—both of which were statistically significant differences.

Less exercise

People with poor/fair health also were more likely to report reduced exercise in response to pandemic stress than people with excellent/good health (35.2 percent vs. 19.8 percent), and they were correspondingly less likely to report exercising more in response to pandemic stress (8.9 percent vs. 21.8 percent). Both of these differences in rates of exercise were statistically significant.

Social connections

As with the other indicators listed in the SHADAC COVID-19 Survey, people with poor/fair health were significantly less likely to report talking more with friends and family to cope with stress than their counterparts with excellent/good health (29.5 percent vs. 43.2 percent).

Coping responses with health risks also found among other subpopulations

The SHADAC COVID-19 Survey also found that certain coping responses with greater potential health risks were more prevalent within other subpopulations:

Higher alcohol consumption by younger adults

Younger adults (age 18-29) were significantly more likely to report increased alcohol consumption than elderly adults (age 65 and older), who had the lowest rate (23.5 percent vs. 4.0 percent), as well as unhealthy changes in eating (eating more, eating more unhealthy foods) as compared with elderly adults, who again reported the lowest rate (48.2 percent vs. 27.1 percent). Younger adults were also significantly more likely to report increased social media use than elderly adults (41.2 percent vs. 23.8 percent).

Females reported higher unhealthy eating habits

Females were more likely to report changes in unhealthy eating (eating more, eating more unhealthy foods) than males (43.2 percent vs. 32.9 percent). Females also were significantly more likely than males to report talking more with friends or family (46.9 percent vs. 33.6 percent), and more likely to report increased social media use (36.5 percent vs. 23.8 percent).

Higher smoking and vaping by people with high school or less education

People with a high school education or less were significantly more likely to report increased smoking or vaping than people with a bachelor’s degree or more (11.9 percent vs. 5.3 percent). They also were less likely to report exercising more (12.5 percent vs. 27.6 percent).

People with higher incomes were more likely to report increased exercise

People with incomes of $100,000 or more were significantly more likely to report increased levels of exercising than those with incomes of less than $30,000 (30.1 percent vs. 11.9 percent). Conversely, people with incomes below $30,000 were significantly more likely to report greater unhealthy eating habits (eating more, eating more unhealthy foods) (44.2 percent vs. 31.6 percent).

Conclusion

Coping strategies are a natural response to increased stress levels due to concerns about the coronavirus pandemic. From the results of the SHADAC COVID-19 Survey, we found variation in coping responses by age, sex, education and income. However, some of the most distinctive differences in stress-coping responses were among people reporting poor or fair health, who reported higher rates of responses with potentially negative health impacts, such as increased alcohol consumption, reduced exercise and unhealthy eating habits. People with poor or fair health also reported lower rates of talking more with friends and family, raising concerns about greater social isolation for these people at a time when stay-at-home-orders have been official policies in many states.

It is critical that individuals are aware of their stress levels and the methods by which they are using to cope, and make sure that they take care of themselves and others. It is also critical to reach out to people with poorer health, who may need increased social supports during times of an economic and public health crisis. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the following activities as ways to deal with stress 1:

- Take breaks from the news.

- Take care of your body, including eating well-balanced healthy meals, exercise, get enough sleep, and avoid alcohol and drugs.

- Schedule time to unwind and do activities that you enjoy.

- Connect with others, including people you trust, family, and friends.

Moderating stress levels with healthy behaviors can contribute to an overall feeling of health and wellbeing that is important to cultivate during this time of an unprecedented pandemic.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, April 30). Stress and coping. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/cope-with-stress/index.html

Blog & News

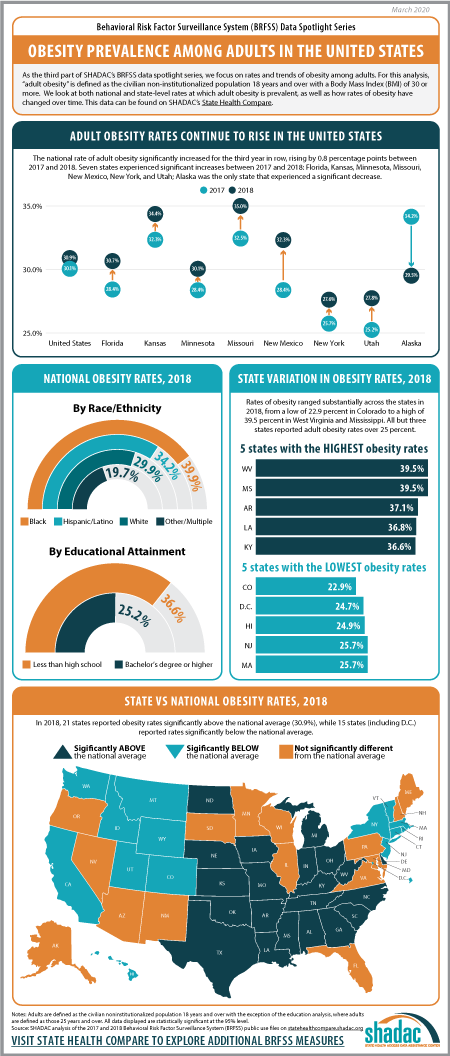

BRFSS Spotlight Series: Adult Obesity Prevalence in the United States (Infographic)

March 17, 2020:|

BRFSS SPOTLIGHT SERIES OVERVIEW |

Click on the infographic image to enlarge

Adult Obesity

For the final post in our BRFSS Spotlight Series blog, we focused on trends in adult obesity rates. Though much attention has been paid to issues such as the opioid crisis or the rapid rise in youth vaping and e-cigarette use, the prevalence of obesity in the United States since the 1980s has made this one of the longest-running, currently declared public health emergencies in the nation.1

“Obesity” is defined as a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 30 and over, and the measure of “Adult Obesity” from the BRFSS encapsulates the self-reported prevalence of obesity among adults for the civilian non-institutionalized population 18 years and over. In using these BRFSS estimates, it is important to understand that self-reported data like these underestimates obesity rates as compared with the measured data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). A 2016 research article from Ward et al. demonstrates a bias correction method for the BRFSS estimates that is beyond the scope of this analysis, but may be of interest to researchers.

Trends in Obesity Rates from 2017 to 2018*

The rate of adult obesity significantly increased for the third year in row nationwide from 2017 to 2018, rising by 0.8 percentage points to 30.9 percent from 30.1 percent in 2017.

Seven states experienced statistically significant increases in the rate of adult obesity from 2017 to 2018: Florida, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, and Utah. Alaska was the only state to experience a statistically significant decline in the rate of obesity, decreasing 4.6 percentage points from 34.2 percent in 2017 to 29.5 percent in 2018.

Overall, however, a large majority of states (43 including D.C.) did not experience a statistically significant change in obesity rates from 2017.

State Variation (2018)

Rates of obesity ranged substantially across the states in 2018, from a high of 39.5% in West Virginia and Mississippi to a low of 22.9% in Colorado. When compared to the national rate…

- 21 states had obesity rates that were significantly higher.

- 15 states (including DC) had obesity rates that were significantly lower.

- 15 states had obesity rates that were not statistically different.

Persistently high rates of obesity are concerning in their own right, but also because obesity increases the risk for other serious health conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and certain types of cancers, among many others.2

Unfortunately, current projections for the future indicate that the already high rates of obesity in America will only continue to increase. Without new interventions to prevent the spread of obesity, a new study using data from the BRFSS and published in the New England Journal of Medicine predicts that by 2030, nearly half of the United States population (48.9 percent) will be considered obese, with over a quarter of the nation registering as severely obese.

Notes

*All differences described here are significant at the 95% level of confidence unless otherwise specified.

For this analysis, adults are defined as those age 18 and over.

Estimates are from SHADAC analysis of the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and are available on State Health Compare.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (1999, October 26). Obesity epidemic increases dramatically in the United States: CDCD director call for national prevention effort. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/r991026.htm

Health tidbits. (1999). J Natl Med Assoc, 91(12), 645. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2608606/

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, February 4). Adult obesity causes & consequences. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html#Consequences