Blog & News

Measuring Health Care Affordability with State Health Compare: Trouble Paying Medical Bills

June 18, 2019:The cost of health care continues to grow nationwide, with U.S. health care spending reaching $3.5 trillion, or an average of $10,739 per person, in 2017.[1] As these expenditures have grown, the cost of health insurance has grown as well, such that Americans are increasingly enrolling in health plans with large deductibles and other cost sharing in order to avoid the expense of rising premiums. Rising enrollment in these health plans, combined with the ongoing problem of “surprise medical bills” (bills from providers who are out of network unbeknownst to consumers) across all plan types, has increased the health care cost burden for many Americans and has drawn increasing attention to the affordability of health care for consumers.[2]

Exploring Health Care Affordability at the State Level with State Health Compare

SHADAC’s State Health Compare includes a measure “Had Trouble Paying Medical Bills” that assesses changes and patterns in health care affordability across the country by tracking the percent of Americans that had difficulty paying off medical bills or that were paying off medical bills over time. The measure is available at both the state and national level for 2011-2016 and can be broken down by age and insurance coverage type.

This post highlights states that experienced changes in the percent of residents by age that had trouble paying medical bills between 2015 and 2016 and shows the substantial amount of variation across states on this measure.

Trouble paying medical bills among the states, 2015-2016: Some rate increases, no decreases

Nationally, the percent of nonelderly adults (age 19-64) reporting trouble paying medical bills increased from 29.2% in 2015 to 31.3% in 2016 (2.1 points). This pattern was mirrored among children (age 0-18), who experienced an increase of 2.8 points, from 32.5% in 2015 to 35.3% in 2016.

Eight states experienced statistically significant increases in the share of nonelderly adults reporting trouble paying medical bills between 2015 and 2016, as shown below. Montana had the largest increase at 11.4 points (from 28.0% in 2015 to 39.4% in 2016), followed by Nevada at 10.4 points (from 18.2% to 26.8%), and New Hampshire at 7.4 points (from 26.8% to 34.2%). No state experienced a statistically significant decrease in the percent of non-elderly adults reporting trouble paying medical bills.

Among children, four states saw significant increases in the share reporting trouble paying medical bills, also shown below. The largest of these increases was in Arkansas, which experienced a rise of 18.0 points from 30.2% to 48.2% between 2015 and 2016. No state saw a significant decrease in the percent of children whose family reported trouble paying medical bills.

Among elderly adults (65+), only Alabama and Montana experienced significant increases in the share reporting trouble paying medical bills. Those states saw increases of 8.4 and 7.1 percentage points, respectively. No state saw a significant decrease in the percent of elderly adults reporting trouble paying medical bills.

2016: Large variation across states in percent with trouble paying medical bills

As shown below, there was substantial variation across states in 2016 in the percent that had trouble paying medical bills among nonelderly adults, children, and elderly adults. In general, states with median incomes registering below the national median[3] tend to have higher shares of residents reporting trouble paying medical bills, regardless of age group, and vice versa.

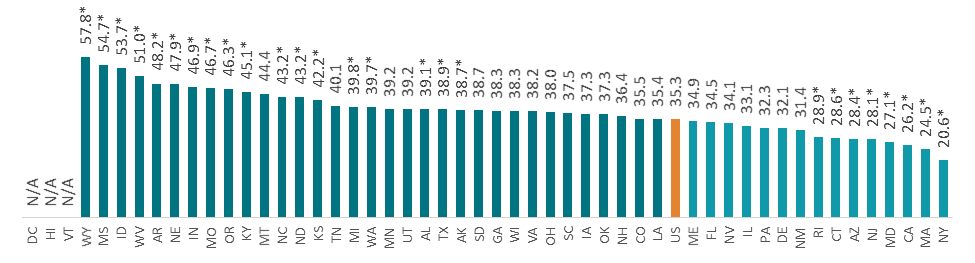

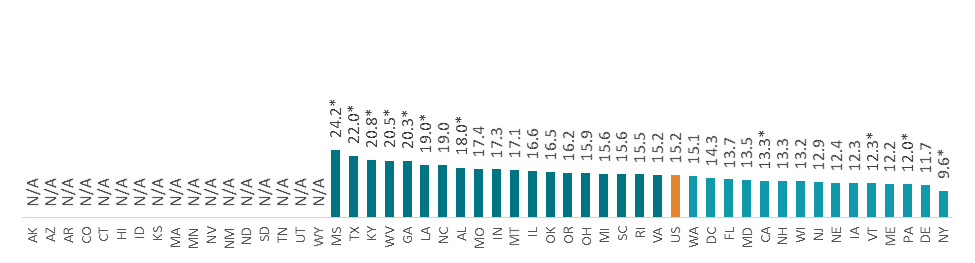

The percent of nonelderly adults who had trouble paying medical bills ranged from 13.3% in the District of Columbia to 49.0% in Mississippi (a difference of 35.7 points); the percent of children in families that had trouble paying medical bills ranged from 20.6% in New York to 57.8% in Wyoming (a difference of 37.2 points); and the percent of elderly adults who had trouble paying medical bills ranged from 9.6% in New York to 24.2% in Mississippi (a difference of 14.6 points).

Percent That Had Trouble Paying Medical Bills by State, 2016

Notes and Definitions

“Had Trouble Paying Medical Bills” is defined as the rate of individuals that had trouble paying off medical bills during past twelve months or were currently paying off medical bills among the civilian non-institutionalized population.

The source of the estimates is SHADAC analysis of NHIS data, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The NHIS sample is drawn from the Integrated Health Interview Survey (IHIS, MN Population Center and SHADAC). Data were analyzed at the University of Minnesota's Census Research Data Center because state identifiers were needed to produce results and these variables were restricted.

Estimates were created using the NHIS survey weights, which are calibrated to the total U.S. Civilian non-institutionalized population for estimates broken down by age, and to the civilian non-institutionalized population age 18 to 64 for estimates broken down by coverage type.

Though SHADAC goes to great effort to produce as many state-level estimates as possible for our measures, due to sample size restrictions many state estimates of this measure are suppressed when broken down by subgroup. Namely, estimates are suppressed if the number of sample cases was too small or the estimate had a relative standard error greater than 30 percent.

Other State Health Compare estimates that use data from the NHIS

Had Trouble Paying Medical Bills is one of eight State Health Compare measures that SHADAC produces using data from the NHIS listed below. State Health Compare is the only source for state-level estimates of these measures.

- Made Changes to Medical Drugs

- Trouble Paying Medical Bills

- No Trouble Finding Doctor

- Told that Provider Accepts Insurance

- Had Usual Source of Medical Care

- Had General Doctor or Provider Visit

- Had Emergency Department Visit

- Spent the Night in a Hospital

[1] Centers for Medicaid & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2018. National Health Expenditure Data: Historical. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountshistorical.html

[2] Pollitz, K. (2016, March 17). Surprise Medical Bills. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/surprise-medical-bills/

[3] See U.S. Census Bureau, Table S1903. Median Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2016 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars): 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/16_1YR/S1903/0100000US|0100000US.04000

* Difference from the U.S. significant at the 95% confidence level

N/A indicates that data were suppressed because the number of sample cases was too small or the estimate had a relative standard error greater than 30%

Universe: Civilian non-institutionalized population

Source: SHADAC analysis of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)

Publication

The Opioid Epidemic: National and State Trends in Opioid-Related Overdose Deaths from 2000 to 2017 (Briefs)

Over the past two decades, the United States has experienced a growing crisis of substance abuse and addiction that is illustrated most starkly by the rise in deaths from drug overdoses. Since 2000, the annual number of drug overdose deaths has quadrupled from 17,500 to 70,000 in 2017.1,2 Most of these deaths involved opioids, including heroin, prescription painkillers, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.3

However, in the years since the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared overdoses from prescription painkillers an “epidemic” in 2011, the opioid overdose crisis has evolved rapidly from a problem tied mostly to prescription opioid painkillers to one increasingly driven by illicitly trafficked heroin and synthetic opioids. More recently, early evidence suggests that the problem also may be spreading beyond opioids to other illicit drugs, such as cocaine and psychostimulants (e.g., methamphetamine).

These two briefs, produced by SHADAC researchers, provide high-level information about opioids and opioid addiction, present the historical context for the epidemic of opioid-related addiction and mortality in the United States, and examine trends in opioid-related mortality across the nation, across states, and among population subgroups. Additionally, due to growing concern and evidence that the opioid crisis may be expanding to other non-opioid illicit drugs, the briefs have been expanded this year to include data on drug overdose deaths from cocaine and psychostimulants, the two types of drugs that are most commonly involved in opioid overdoses.4,5

1 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. (2017). Drug Poisoning Mortality: United States, 1999-2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-visualization/drug-poisoning-mortality

2 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, January 4). Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2013-2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(5152), 1419-1427. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm675152e1.htm?s_cid=mm675152e1_w

3 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, December 30). Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2010-2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(50-51), 1445-1452. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm655051e1.htm

4 Although reports of illicit drugs being tainted with synthetic opioids are relatively common, it is unclear whether deaths involving multiple drugs are typically the result of drugs being intentionally mixed by or unintentionally contaminated through traffickers’ sloppiness, or because individual drug users are concurrently abusing multiple different drugs of their own volition.

5 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, December 12). Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths: United States, 2011-2016. National Vital Stastics Report, 67(9), 1-14. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_09-508.pdf

Blog & News

SHADAC at the 2019 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (ARM)

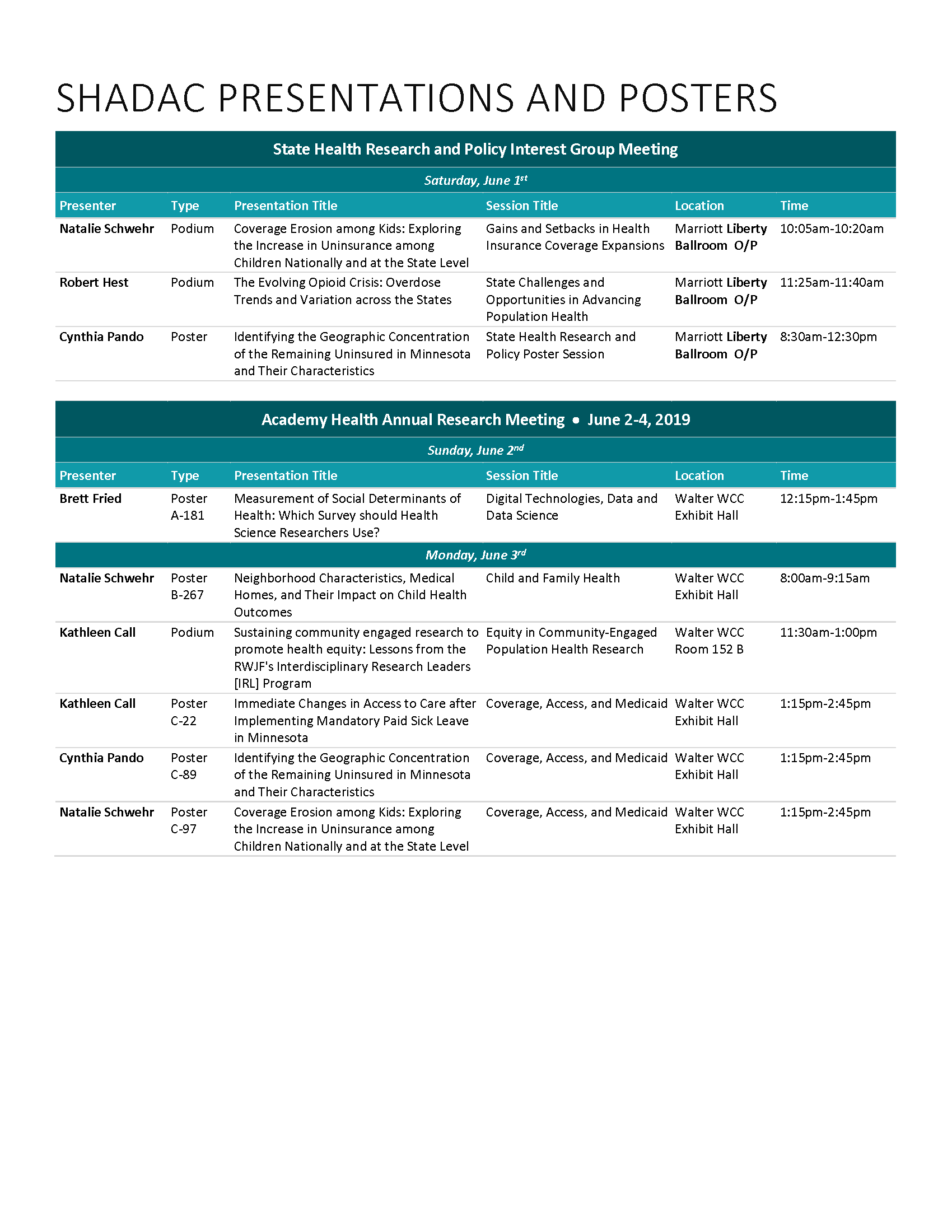

May 29, 2019:A number of SHADAC researchers will be presenting their research at the 2019 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (ARM) in Washington, D.C., from Sunday, June 2nd to Tuesday, June 4th, and at the State Health Research and Policy Interest Group Meeting on Saturday, June 1st. Their presentations include:

The Evolving Opioid Crisis: Overdose Trends and Variation across the States

The Evolving Opioid Crisis: Overdose Trends and Variation across the States

Robert Hest - State Health Policy and Research Interest Group

Coverage Erosion among Kids: Exploring the Increase in Uninsurance among Children Nationally and at the State Level

Natalie Schwehr - State Health Policy and Research Interest Group

Identifying the Geographic Concentration of the Remaining Uninsured in Minnesota and Their Characteristics

Cynthia Pando - State Health Policy and Research Interest Group

Coverage Erosion among Kids: Exploring the Increase in Uninsurance among Children Nationally and at the State Level

Natalie Schwehr

Sustaining community engaged research to promote health equity: Lessons from the RWJF's Interdisciplinary Research Leaders (IRL) Program

Kathleen T. Call

Medical Homes, Neighborhood Characteristics, and Their Impact on Child Health Outcomes

Natalie Schwehr

Immediate Changes in Access to Care after Implementing Mandatory Paid Sick Leave in Minnesota

Kathleen Call (SHADAC)

Identifying the Geographic Concentration of the Remaining Uninsured in Minnesota and Their Characteristics

Cynthia Pando

Visit Us in the Exhibit Hall - Booth #212

SHADAC researchers will be available at the SHADAC booth to answer your questions about state and national data sources on coverage, access, and costs; to discuss our technical assistance offerings; and to walk visitors through State Health Compare. Stop by to chat, check out some of our latest projects, and grab some swag! Be sure to tag and hashtag us (@SHADAC and #SHADACatARM2019) on Twitter to keep up with what we're doing at the conference!

The full presentation schedule for SHADAC faculty, staff, and students can be downloaded by clicking the document on the right.

Blog & News

2018 NHIS Full-Year Early Release: Insurance Coverage Held Steady Overall, with Some Subgroup Changes

May 15, 2019:The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) released health insurance coverage estimates for 2018 from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) as part of the NHIS Early Release Program. These are the first available full-year coverage estimates for 2018 from a federal survey, with estimates available for the U.S. and 17 states.

Key Findings

Uninsurance

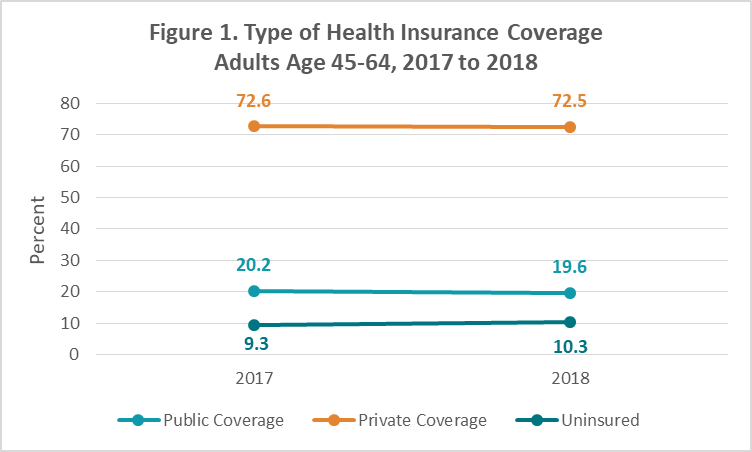

Approximately 30.4 million persons of all ages, or 9.4%, were uninsured nationwide in 2018. This uninsured rate was statistically unchanged from 2017, as were the rates in the 17 states for which the NHIS provided 2018 estimates.[1] Uninsurance also held steady among most populations by age, sex, race/ethnicity, Marketplace type, state, state Medicaid expansion status, and region. There were, however, significant increases in uninsurance among adults age 45-64 (from 9.3% to 10.3%) who, the report noted, were the most likely group to be uninsured, and among nonelderly adults (age 18-64) with household incomes above 400% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

Public and Private Coverage

Like uninsurance, public coverage and private coverage held steady nationwide in 2018 at 36.7% and 62.3%, respectively. Public and private coverage were also largely stable in the 17 select NHIS states, with the exception of New York, where public coverage increased in 2018 from 38.9% to 43.6%, and Virginia, where public coverage increased from 31.8% to 38.4%. Public coverage also increased from 67.9% to 72.7% among children (age 0-17) with household incomes from 100% to 200% FPL. Private coverage decreased from 26.5% to 21.4% among non-elderly adults with incomes below 100% FPL.

Behind the Numbers

From 2017 to 2018, premiums for silver Marketplace plans increased an average of 32%, with bronze premiums rising 17% and gold premiums rising 18%.[2] Since 45-64 year-olds are subject to age rating both on and off the Marketplace, they face even higher premiums than average, while individuals above 400% FPL are ineligible for Marketplace subsidies and therefore face the entire cost of premium increases. With this in mind, increasing uninsurance among these two groups suggests that some were dropping coverage in response to rising premium costs in 2018. An increase in the rate of high-deductible health plan (HDHP) enrollment, which grew from 43.7% in 2017 to 45.8% in 2018 among the nonelderly (age 0-65) nationwide, provides additional evidence that premium increases played a role in 2018 coverage changes, as individuals may be responding to rising premium costs by shifting to coverage with higher deductibles.

About the Numbers

The above estimates provide a point-in-time measure of health insurance coverage, indicating the percent of persons with that type of coverage at the time of the interview. The 2018 estimates based on a sample of 72,762 persons from the civilian noninstitutionalized population, a decrease from the 2017 sample of 78,074 persons.

For more information about the early 2018 NHIS health insurance coverage estimates, read the National Center for Health Statistics brief.

[1] Significant differences between 2017 and 2018 are at the 95% confidence level or greater.

[2] Semanskee, A., Claxton, G., & Levitt, L. (November 29, 2017). How Premiums Are Changing in 2018. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/how-premiums-are-changing-in-2018/

Citation

Cohen, R.A., Terlizzi, E.P., & Martinez, M.E. (May 2019). Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2018 [PDF file]. National Center for Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey Early Release Program. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201905.pdf

Blog & News

New SHADAC Brief Explores Methods for Adapting BRFSS Survey Income Measure to Align with FPG Thresholds

June 18, 2019: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey can be a valuable data source for researchers seeking to evaluate the impact of health insurance coverage programs such as Medicaid on measures of health outcomes and health behaviors; yet the BRFSS’ income measure, which asks respondents to classify their income within one of eight possible categories, creates challenges when trying to define the relevant eligible populations.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey can be a valuable data source for researchers seeking to evaluate the impact of health insurance coverage programs such as Medicaid on measures of health outcomes and health behaviors; yet the BRFSS’ income measure, which asks respondents to classify their income within one of eight possible categories, creates challenges when trying to define the relevant eligible populations.

A new brief from SHADAC evaluates common methods for better using categorical income measures, such as the one in the BRFSS, to calculate income as a percent of the federal poverty guidelines (FPG).

Evaluation and Methods

Three of the four methods start by assigning a continuous income value to the respondent based on the respondent’s reported income category, choosing either the lower bound of each category, the upper bound of each category, or the midpoint of each category. A fourth method utilizes the uniform distribution to randomly assign an income value within the reported category.

Employing data from the 2017 BRFSS, the brief presents the distribution of income as a percent of FPG produced by each method as well as the state-level poverty rates produced by each method. It then evaluates the accuracy of these methods using data from the 2018 Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC), which has both a categorical income measure and a continuous income measure. The brief compares the distribution of income as a percent of FPG produced by the CPS’s continuous income measure to the distributions of income produced by each method when applied to the CPS’s categorical income measure.

Conclusions

Evaluation results reveal substantial differences in the distribution of income as a percent of FPG produced by each of the methods. The brief shows that the lower bound method skews towards the lower part of the income distribution, that the uniform distribution and midpoint methods produce a more even distribution of income, and that the upper bound method skews towards the upper part of the income distribution. Comparing the distributions produced by these methods against the distribution from a continuous income measure, the brief concludes that the upper bound method is likely the most accurate method across the income distribution while also acknowledging that the best method for assigning continuous income remains partially dependent on which population(s) is most relevant to the researcher’s chosen outcomes for analysis.

SHADAC utilizes data from the BRFSS, CPS, and other federal surveys to produce measures on a range of topics including income inequality, social and economic determinants of health, health insurance coverage, cost of care, health behaviors and outcomes, access to and utilization of care, and public health. Visit our State Health Compare web tool to explore the data further.

Related Resources

FPG vs. FPL: What’s the Difference?