Blog & News

Vaccine Hesitancy Decreased During the First Three Months of the Year: New Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey

May 14, 2021:Evidence shows that marginalized groups such as individuals with lower-incomes and people of color are in general less likely to receive vaccinations.i Previous research from SHADAC using the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS) confirms that this pattern holds true with the COVID-19 vaccine as well.ii] Understanding why certain subpopulations are not receiving COVID-19 vaccines is crucial to improving equity of vaccinations. However, it is difficult to separate operational barriers from social ones when looking solely at vaccination rates. This blog uses data from the HPS to illuminate the latter by looking at vaccine hesitancy among U.S. adults (age 18 and older) for January – March 2021, by region, race/ethnicity, income, and reported reasons for hesitancy.

|

The HPS is an ongoing weekly tracking survey designed to measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. |

The HPS defines vaccine hesitancy as reporting at least one of 11 reasons to not receive the vaccine within a given survey week.iii These reasons include:

| 1) Concerned about possible side effects 2) Plan to wait and see if it is safe and may get it later 3) Think other people need it more than I do right now 4) Don't know if a COVID-19 vaccine will work |

5) Don't trust COVID-19 vaccines

6) Don't trust the government

7) Don't believe I need a COVID-19 vaccine

8) Don't like vaccines

|

9) Concerned about the cost of a COVID-19 vaccine 10) My doctor has not recommended it 11) Other Reason |

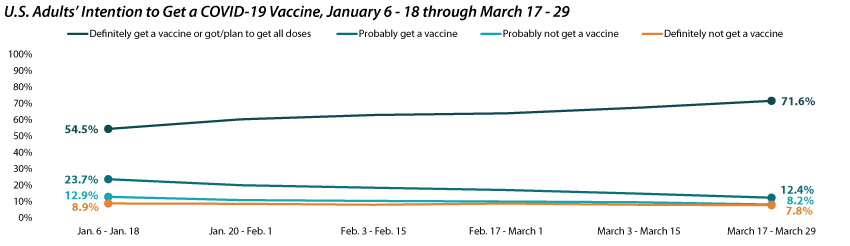

The share of adults who would definitely get a COVID-19 vaccine increased to more than 70%.

Nationally, the percent of adults who had already received or “definitely” would get a COVID-19 vaccine increased substantially, from 54.5% during January 6 - 18 to 71.6% by March 17 - 29. Over the same period, the share who reported that they would “probably” get a vaccine fell by almost half, from 23.7% to 12.4%. The percent who said they would “probably not” or “definitely not” get a COVID-19 vaccine were lower but more stable, shifting from 12.9% to 8.2% and from 8.9% to 7.8%, respectively over the same period.

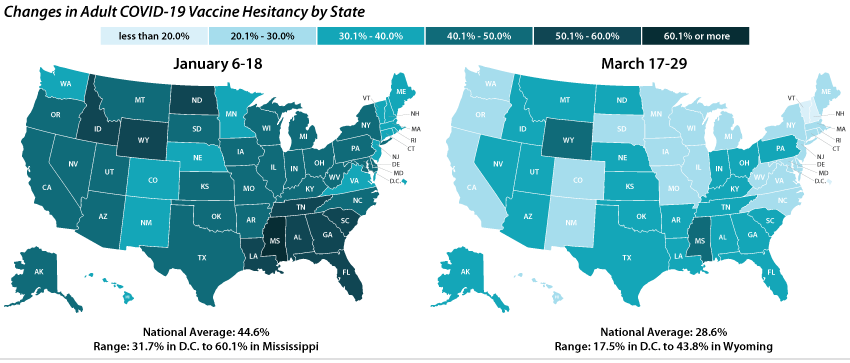

Vaccine hesitancy varied dramatically by state, but nearly all states saw decreases.

Nationally, 28.6% of adults reported one or more reason for not getting a COVID-19 vaccine during March 17 – 29, and this varied across the states, from 17.5% in the District of Columbia to 43.8% in Wyoming. One in three adults cited one or more reasons for not getting a COVID-19 vaccine in 13 states.

The national rate of adult vaccine hesitancy decreased by 16.0 percentage points (PP) between January 6-18 and March 17-29 (44.6% to 28.6%). All states but Nebraska saw decreases in rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy over the same period.

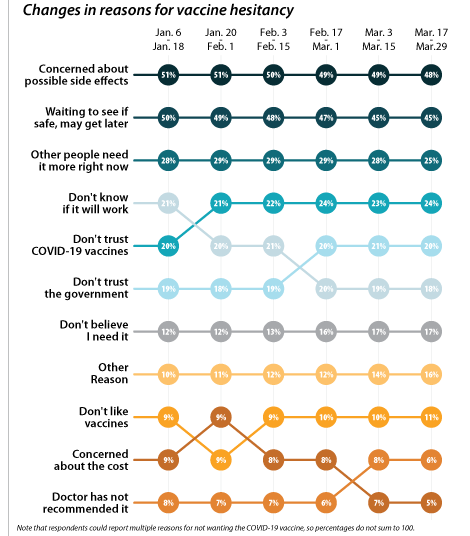

Concerns over possible side effects and safety were the top two reported reasons for vaccine hesitancy.

Of the 28.6% of respondents who reported vaccine hesitancy during the March 17-29 period, 47.8% cited concerns about possible side effects of the vaccine and 43.7% cited wanting to wait to see if the vaccine was safe. As a proportion of all reasons cited by the hesitant population, these two have decreased slightly over the first three months of the year, but still remain the top two reasons for vaccine hesitancy overall. The next most cited reason during the same survey period was “I think other people need it more than I do right now” at 25.0%. These rankings hold within subpopulations such as region, race, and income. The average number of reasons for hesitancy reported was 2.3 per respondent.

While concerns about potential side effects, safety, priority, and efficacy have been decreasing, distrust of the COVID-19 vaccines and distrust of the government, along with not believing that “I need a COVID-19 vaccine” have all increased as stated reasons for vaccine hesitancy. This could be cause for concern, since these reasons for hesitancy may not fade as individuals see more people in their communities getting safely vaccinated.

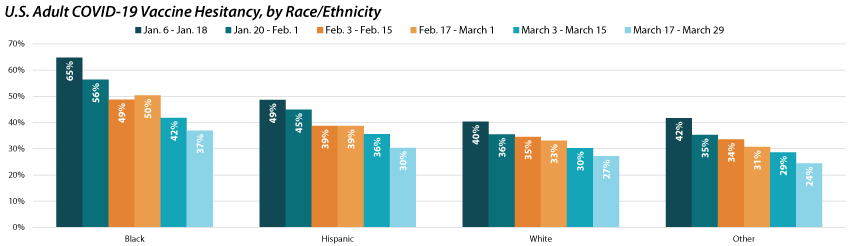

Disparities in vaccine hesitancy rates improved over time, but leveled out amongst certain demographics.

A similar story emerges when looking at hesitancy across demographic and socioeconomic factors; hesitancy has improved over time, but with distinctions across subpopulations. For example, hesitancy rates among Black adults have decreased from 64.7% to 36.9% but remain much higher than among other racial/ethnic groups.

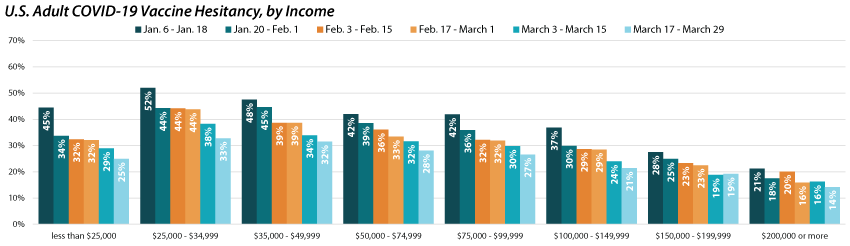

Similar to vaccination rates, we find disparities in hesitancy across income categories with rates decreasing as income increases. These disparities have slightly closed over time as there has been a greater reduction in hesitancy rates for those making less than $50,000 than those making more than $50,000. However, there’s still a stark difference across groups as those with incomes between $25,000 and $34,999 continued to be more than twice as likely as those with incomes of $200,000 or greater to report vaccine hesitancy.

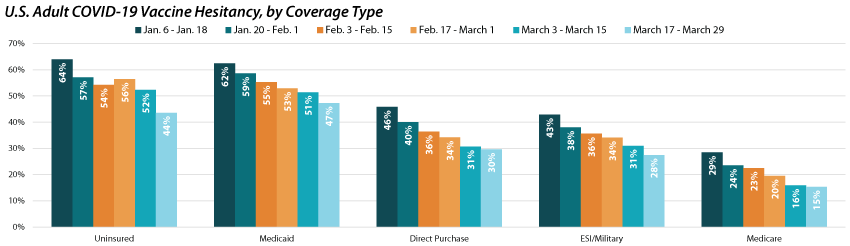

As shown by previous analysis, groups with fewer connections to the health care system, such as those without health insurance coverage will likely be some of the hardest to reach with COVID-19 vaccinations. This concern is borne out in rates of hesitancy by insurance status. Though rates of hesitancy have fallen for both those with and without health insurance coverage, the uninsured remain more likely to report hesitancy (43.6%) compared to those with employer-sponsored (ESI)/Military, Direct Purchase, or Medicare coverage. Adults with Medicaid were also more likely to report vaccine hesitancy (47.3%) compared with adults with ESI/Military, Direct Purchase, or Medicare coverage.

Notes:

All changes and differences in this post are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level unless otherwise noted.

Related Reading

SHADAC Brief: Anticipating COVID-19 Vaccination Challenges through Flu Vaccination Patterns

SHADAC Blog Series: Measuring Coronavirus Impacts with the Census Bureau's New Household Pulse Survey: Utilizing the Data and Understanding the Methodology

50-State Infographics: A State-level Look at Flu Vaccination Rates among Key Population Subgroups

i Planalp, C. & Hest, R. (2021). Anticipating COVID-19 Vaccination Challenges through Flu Vaccination Patterns. State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC). https://www.shadac.org/publications/anticipating-covid-19-vaccination-challenges-through-flu-vaccination-patterns

ii State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC). (2021). Measuring Coronavirus Impacts with the Census Bureau's New Household Pulse Survey: Utilizing the Data and Understanding the Methodology. https://www.shadac.org/Household-Pulse-SurveyMethods

iii The following respondents are given 11 reasons to select from for why they would not “definitely” get a COVID-19 vaccine: respondents who…

a. Had not received a COVID-19 vaccine and reported that they would not “definitely get a vaccine” once it was available to them;

b. Or had gotten one dose of a two-dose COVID-19 but did not plan to get the second dose.

Blog & News

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Analysis of the Household Pulse Survey

April 14, 2021:Update 5: March 17 to March 29

Newly available COVID-19 vaccines promise to help protect individual Americans against infection and eventually provide population-level herd immunity. The pace of COVID-19 vaccination rollout in the United States has picked up after an unsteady start earlier in the year. The country is on track to meet the current administration’s new goal of immunizing 200 million in Biden’s first 100 days in office, despite hiccups in the rollout of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The initial groups prioritized for vaccination were healthcare workers on the front lines of the pandemic and nursing facility residents, many of whom are especially vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and severe outcomes. While these and other high-priority groups continue to be first in line for vaccination slots, many states have since expanded vaccine access to the general adult population. However, there are concerns that these early prioritization decisions and the existing mechanisms of the vaccine rollout—in addition to evidence that lower-income individuals, people of color, and individuals without strong connections to the health care system are less likely to get vaccinated—have created challenges in equitably distributing the COVID-19 vaccine and could worsen existing pandemic-related health inequities.

The available data have not assuaged these concerns and show patterns of lower vaccination rates among people with lower incomes and levels of education and marginalized racial and ethnic groups. The U.S. Census Bureau recently released updated data on take-up of COVID-19 vaccines from the latest wave of its Household Pulse Survey (HPS), collected March 17 - 29, 2021.1 The HPS is an ongoing, weekly tracking survey designed to measure impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. These data provide an updated snapshot of COVID-19 vaccination rates and are the only data source to do so at the state level by subpopulation.

This blog post presents top-level findings from the new data, focusing on rates of vaccination (one or more doses) among U.S. adults (age 18 and older) living in households and comparing the results to the most recent wave of the HPS, collected March 3 - 15, 2021.2

These data represent the last release from Phase 3 of the HPS. Data collection for Phase 3.1 will begin April 14 after a two-week break to make tweaks to questionnaire content. It is anticipated that the first results from Phase 3.1 will be released on May 5, 2021. Census has indicated that it plans to continue administering the survey through December 2021.

Almost half of U.S. adults had received one or more COVID-19 vaccinations by the end of March.

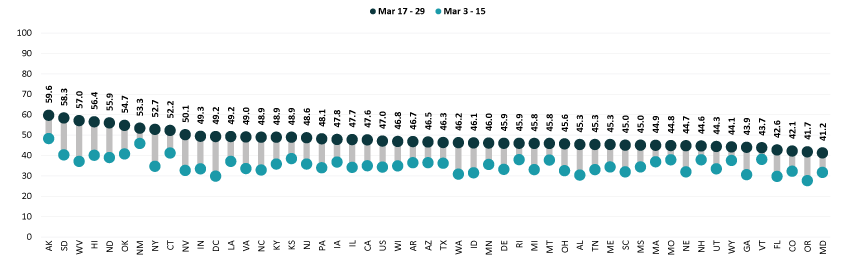

According to the new HPS data, 47.0% of U.S. adults had received one or more vaccinations by March 29th, though this varied by state from a low of 4.12% in Maryland to a high of 59.6% in Alaska. At least one in two adults had received a vaccine in ten states: Alaska, Connecticut, Hawaii, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and West Virginia.

Vaccination rates increased dramatically across nearly all states; states with lower rates catching up

Nationally, adult vaccination rates were up from the previous wave of the HPS, increasing from 34.2% during March 3 - 15, 2021, to 47.0% during March 17 - 29, 2021. Many states experienced a large increase in their vaccination rates. The size of these increases varied from a 5.7 percentage point (PP) increase in Vermont to a 20.0 PP increase in New Mexico. Twelve states saw increases of 15.0 PP or larger.

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine

Disparities in vaccination rates improved, but slowly and unevenly

COVID-19 vaccination rates continued to vary to a great degree by demographic and socioeconomic factors. Gaps in vaccination compared to the national average narrowed slightly for most groups, though some groups saw larger improvements. As with prior weeks, vaccination rates were lower for certain subpopulations such as Hispanic/Latino adults, Black adults, and Other/Multiracial adults, and these rates were particularly low for very-low-income adults and for adults without a high school education. More resources, increased attention, or new strategies may be needed to close the gaps for the hardest-to-reach groups.

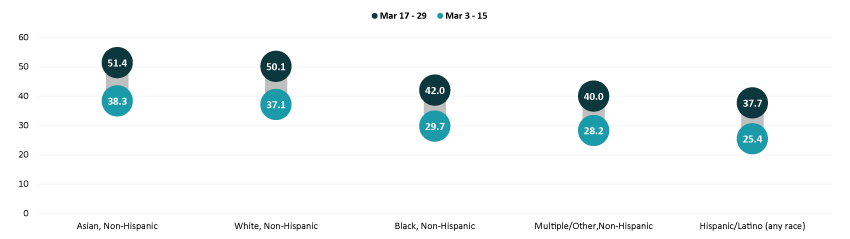

By race and ethnicity, Asian and white adults continued to have above-average vaccination rates at 51.4% and 50.1%, respectively. Rates among Black adults (42.0%), adults identifying with “Multiple” or “Some Other” race (40.0%), and Hispanic/Latino adults (37.7%) continued to be below the national average. However, vaccination rates among Black adults, “Multiple” or “Some Other” race adults, and Hispanic/Latino adults all improved somewhat relative to the national average.

Hispanic/Latino adults had the largest relative improvement, going from 26 percent below the national average in the first half of March (25.4% vs. 34.2%) to 20 percent below the national average in the second half of March (37.7% vs. 47.0%). This was a marked improvement after consistently being 25 to 30 percent below the national average with every bi-weekly release since the beginning of January.

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine by Race/Ethnicity

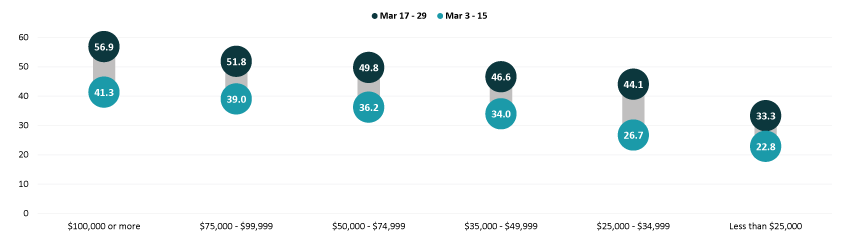

Gaps in vaccination rates among income levels have continued to narrow, however, Adults with household incomes below $50,000 are still falling below the national average, whereas adults with household incomes above $50,000 remain higher than the national average. Vaccination rates among adults with incomes less than $35,000 continued to improve compared to the national average. This improvement was especially large among adults with incomes between $25,000 and $34,999, going from 22 percent below the national average in the first half of March (26.7% vs. 34.2%) to just 6 percent below the national average in the second half of March (46.6% vs. 47.0%).

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine by Income

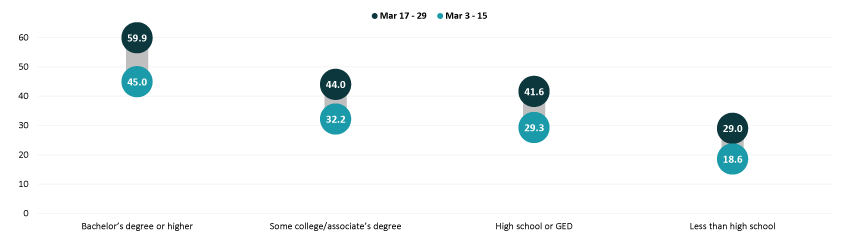

Disparities by level of education remained, with adults that hold a bachelor’s degree or higher continuing to have the highest vaccination rate at 59.9% and adults without a high school diploma having the lowest vaccination rates at 29.0%. Disparities by education did narrow somewhat relative to the national average, especially for adults with a high school education or equivalent and adults with less than a high school level of education. However, adults with less than a high school level of education continued to have the lowest rates of vaccination of any of the groups analyzed here.

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine by Education

Nationally, More than four in five older adults had received a COVID-19 vaccine

Nationally, 80.1% of older adults (age 65 and older) had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, which was 33.1 PP higher than the rate among all adults (47.0%). Vaccination rates for older adults ranged from a low of 67.4% in Hawaii to a high of 90.1% in Connecticut. Hawaii was the only state to have a 65+ vaccination rate of below 70 percent.

As may be expected given the high rates of vaccination in the older adult population, rates of increase in vaccination in this group slowed somewhat in the last half of March. No state increased its 65+ vaccination rate by more than 0.43x (Oregon), whereas ten states were able to increase vaccination rates by 0.5x or more in the first half of the month. Though the 65+ vaccination rates in Alaska appeared to have fallen in the second half of March, this was more than likely a statistical artifact rather than an actual decrease.

Percent of Adults Age 65+ Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine

Notes about the Household Pulse Survey Data

The estimated rates presented in this post were calculated from the count estimates published by the Census Bureau. Though these counts are accompanied by standard errors, standard errors are not able to be accurately calculated for rate estimates. Therefore, we are not able to determine if the differences we found in our analysis are statistically significant or if the estimates themselves are statistically reliable. Estimates and differences for subpopulations at the state level should be assumed to have large confidence intervals around them and caution should be taken when drawing strong conclusions from this analysis. However, the fact that these early indications of COVID-19 inequities mirror patterns of other vaccinations inequities demonstrate reason for concern.

Though produced by the U.S. Census Bureau, the HPS is considered an “experimental” survey and does not necessarily meet the Census’ high standards for data quality and statistical reliability. For example, the survey has relatively low response rates (7.2% for March 17 - 29), and sampled individuals are contacted via email and text message, asking them to complete an internet-based survey. These issues in particular could be potential sources of bias but come with the tradeoffs of increased speed and flexibility in data collection as well as lower costs. A future post will investigate differences between COVID-19 vaccination rates estimated from survey data (such as the HPS) and administrative sources. The estimates presented in this post are based on responses from 77,104 adults. More information about the data and methods for the Household Pulse Survey can be found in a previous SHADAC blog post.

Previous Blogs in this Series

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update 4: 3/3 - 3/15) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update 3: 2/17 - 3/1) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update 2: 2/3 - 2/15) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update: 1/10 - 2/1) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: New State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (1/6 - 1/18) (SHADAC Blog)

Related Reading

State-level Flu Vaccination Rates among Key Population Subgroups (50-state profiles) (SHADAC Infographics)

50-State Infographics: A State-level Look at Flu Vaccination Rates among Key Population Subgroups (SHADAC Blog)

Anticipating COVID-19 Vaccination Challenges through Flu Vaccination Patterns (SHADAC Brief)

New Brief Examines Flu Vaccine Patterns as a Proxy for COVID – Anticipating and Addressing Coronavirus Vaccination Campaign Challenges at the National and State Level (SHADAC Blog)

Ensuring Equity: State Strategies for Monitoring COVID-19 Vaccination Rates by Race and Other Priority Populations (Expert Perspective for State Health & Value Strategies)

SHADAC Webinar - Anticipating COVID-19 Vaccination Challenges through Flu Vaccination Patterns (February 4th) (SHADAC Webinar)

Publication

Data to Inform Research on Integrated Care for Dual Eligibles

This report by SHADAC researchers Lacey Hartman and Elizabeth Lukanen, conducted with support from the Arnold Ventures Foundation, summarizes the findings of a systematic review of data sources that could be used to study the broad topic of integrated care for dual eligibles. The paper concludes with a set of recommendations aimed at addressing key data gaps and advancing the availability of comprehensive, high-quality data for research in this area. In addition to this report, SHADAC has produced a companion Excel table that contains the full abstraction details for each data source.

This work was supported by the Arnold Ventures Foundation.

Blog & News

New SHADAC Resource Explores and Evaluates Available Data Sources to Research Integrated Care for Dual Eligibles

April 1, 2021: The importance of improving care for individuals enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (dual eligibles) has received considerable attention in recent years.1,2,3 Extensive research has shown that dual eligibles account for a disproportionate share of spending within both programs, and the lack of integration between the two programs contributes not only to excess costs but also lower quality care.4,5,6 As a result, states and the federal government have developed a variety of models aimed at improving integration of care for dual eligibles.

The importance of improving care for individuals enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (dual eligibles) has received considerable attention in recent years.1,2,3 Extensive research has shown that dual eligibles account for a disproportionate share of spending within both programs, and the lack of integration between the two programs contributes not only to excess costs but also lower quality care.4,5,6 As a result, states and the federal government have developed a variety of models aimed at improving integration of care for dual eligibles.

A new report by SHADAC researchers Lacey Hartman and Elizabeth Lukanen, conducted with support from the Arnold Ventures Foundation, describes the strengths and limitations of existing data sources that could be used to study the broad topic of integrated care for dual eligibles. A primary focus is whether these data can address research questions aimed at improving care for dual eligibles. The paper summarizes findings by assessing the data sources across four focus areas that are critical to research aimed at dual eligibles: 1) enrollment in integrated care models; 2) analysis of priority subpopulations; 3) LTSS; and 4) enrollee social needs.

The report provides a systematic review of 34 data sources that can produce nationally representative estimates for dually eligible individuals (and/or estimates for all 50 states) and have the potential to inform research on integrated care models. Selections were made based on SHADAC’s extensive prior knowledge in working with a wide variety of data sources, our recent work developing an inventory of evaluations of integrated care models, and a scan of relevant and widely used data repositories such as the Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC) and the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (CCW).

The paper also provides an overview of important gaps and deficiencies within the data (and their implications for researchers seeking to evaluate the impact of integrated care for dual eligible) and concludes with a set of recommendations aimed at addressing these gaps and advancing the availability of comprehensive, high-quality data for research in this area.

In addition to this report, SHADAC has produced a companion Excel table that contains the full abstraction details for each data source.

References

1 Rizer, A. COVID-19: If ever there was a time to care about Medicare-Medicaid integration, it’s now. Arnold Ventures. https://www.arnoldventures.org/stories/covid-19-if-ever-there-was-a-time-to-care-about-medicare-medicaid-integration-its-now/

2 Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS). (2021). Promoting integrated care for dual eligibles (PRIDE). https://www.chcs.org/project/promoting-integrated-care-for-dual-eligibles-pride/

3 Integrated Care Resource Center (ICRC). (2021). Home. https://www.integratedcareresourcecenter.com/

4 Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). (2020). Integrating care for dually eligible beneficiaries: Background and context [Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP; Chapter 1]. MACPAC. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Chapter-1-Integrating-Care-for-Dually-Eligible-Beneficiaries-Background-and-Context.pdf

5 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). (2020). Dual-eligible beneficiaries [Data book; Section 4]. MedPAC. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/july2020_databook_sec4_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

6 Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office. (2015). Fiscal year 2015 report to Congress. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-Office/Downloads/MMCO_2015_RTC.pdf

Blog & News

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey - Update 4

March 25, 2021:Update 4: March 3 to March 15

Newly available COVID-19 vaccines promise to help protect individual Americans against infection and eventually provide population-level herd immunity. The pace of COVID-19 vaccination rollout in the United States has picked up after an unsteady rollout earlier in the year. The country has met the current administration’s goal of administering 100 million COVID-19 vaccines sooner than expected, and further increases in supply are on the horizon as newly authorized Johnson & Johnson vaccines are anticipated to be available in the coming weeks.

The initial groups prioritized for vaccination were health care workers on the front lines of the pandemic and nursing facility residents, many of whom are especially vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and severe outcomes. While these groups continue to hold priority in vaccination slots, many states have since expanded vaccine access to other (still high-priority) segments of the general population. Additionally, a growing number of states have now expanded eligibility to all adults. However, there are concerns that these prioritization decisions and the existing mechanisms of the vaccine rollout—in addition to evidence that lower-income individuals, people of color, and individuals without strong connections to the health care system are less likely to get vaccinated—are inadequate to narrow the clear disparities in the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine and could worsen existing pandemic-related health inequities.

The available data have not assuaged these concerns, and show patterns of lower vaccination rates among people with lower incomes and levels of education, and marginalized racial and ethnic groups. The U.S. Census Bureau recently released updated data on take-up of COVID-19 vaccines from the most recent wave of its Household Pulse Survey (HPS), collected March 3 - 15, 2021.1 The HPS is an ongoing, weekly tracking survey designed to measure the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. These data provide an updated snapshot of COVID-19 vaccination rates and are the only data source to do so at the state level by subpopulation.

This blog presents top-level findings from these new data, focusing on rates of vaccination (one or more doses) among U.S. adults (age 18 and older) living in households and how these findings compare to results from the most recent wave of the HPS, collected February 17 - March 1, 2021.2

The current phase of the HPS is slated to continue data collection through the end of March 2021, after which time the survey may be out of the field while changes are made to questionnaire content before returning in April. Census has indicated that it plans to continue administering the survey through December 2021.

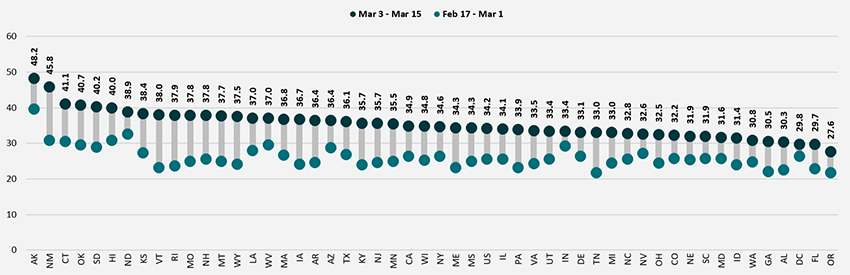

Nationally, more than one in three adults received a vaccination, but this varied by state

According to the new HPS data, 34.2% of U.S. adults had received one or more COVID-19 vaccinations by the end of the second week in March, though this varied by state from a low of 27.6% in Oregon to a high of 48.2% in Alaska. At least four in ten adults had received a vaccine in six states: Alaska, Connecticut, Hawaii, Oklahoma, and South Dakota.

Vaccination rates increased substantially across nearly all states; states with lower rates catching up

Nationally, adult vaccination rates were up from the previous wave of the HPS, increasing from 25.5% during February 17–March 1, 2021, to 34.2% during March 3–15, 2021. Every state experienced an increase in their vaccination rates, though the size of these increases varied from a 3.5 percentage point (PP) change in the District of Columbia to a 15.0 PP in New Mexico.

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine

Disparities in vaccination rates improved, but slowly and unevenly

COVID-19 vaccination rates continued to vary to a great degree by demographic and socioeconomic factors. Gaps between most groups and the national average were largely unchanged from previous weeks, though some groups did see improvements. As with prior weeks, vaccination rates were lower for certain subpopulations such as Hispanic/Latino adults, Black adults, and Other/Multiracial adults, low-income adults, and for adults without a high school education. More resources and attention may be needed to close the gaps for the hardest-to-reach groups.

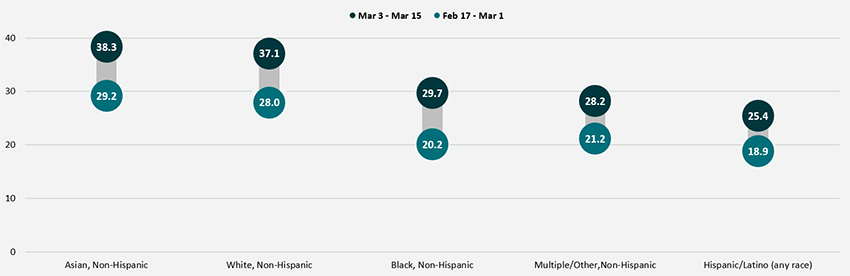

By race and ethnicity, Asian and White adults continued to have above-average vaccination rates at 38.3% and 37.1%, respectively. Rates among Black adults (29.7%), adults identifying with “Multiple” or “Some Other” race (28.2%), and Hispanic/Latino adults (25.4%) continued to be below the national average. However, vaccination rates among Black adults did improve somewhat relative to the national average, going from 21 percent below the national average (20.2% vs. 25.5%) in the second half of February to 13 percent below the national average (29.7% vs. 34.2%) in the first half of March.

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine by Race/Ethnicity

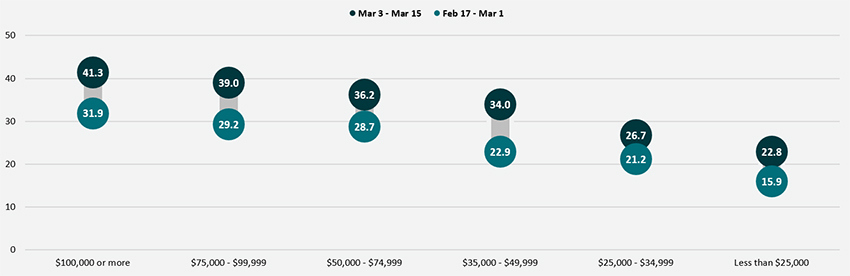

Disparities in vaccination rates by income continued to narrow, though progress was very slow and uneven across income groups. Adults with household incomes below $50,000 continued to have vaccination rates below the national average, whereas adults with household incomes above $50,000 had vaccination rates higher than the national average. However, the size of the gaps between the highest income and lowest income groups narrowed somewhat. Whereas in the second half of February adults with household incomes of $100,000 or higher had vaccination rates nearly 2.0x those of adults with incomes less than $25,000, that gap had narrowed slightly to 1.8x in the first half of March.

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine by Income

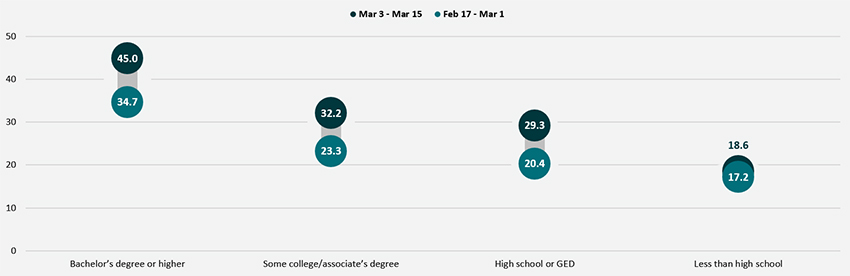

Disparities by level of education remained, with adults holding a bachelor’s degree or higher continuing to have the highest vaccination rate at 45.0%, and adults without a high school diploma having the lowest vaccination rates at 18.6%. Though adults with some college or an associate’s degree and adults with a high school degree or equivalent saw solid growth in their vaccination rates, almost no progress was made among adults without a high school diploma or equivalent. The gap between that group and the national average widened in the first half of March to 46 percent below the national average (18.6% vs. 34.2%) from 32 percent below the national average (17.2% vs. 25.5%) in the second half of February.

Percent of Adults Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine by Education

Nationally, More than two-thirds of older adults received a COVID-19 vaccine and many states continued to make considerable progress in vaccinating older adults

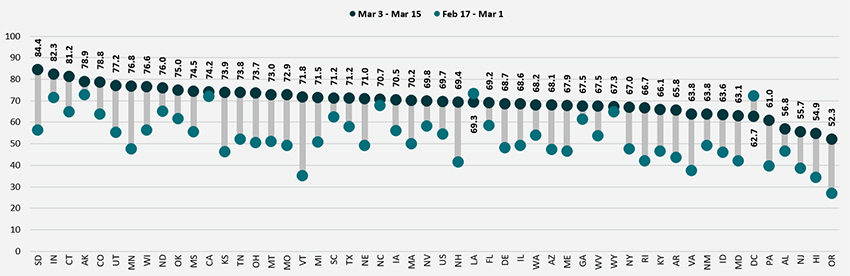

Nationally, 69.7% of older adults (age 65 and older) had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, which was 35.5 percentage points higher than the rate among all adults (34.2%). Vaccination rates for older adults ranged from a low of 52.3% in Oregon to a high of 84.4% in South Dakota. Older adult vaccination rates were below 60% in just four states (Alabama, Hawaii, New Jersey and Oregon) and at or above 75% in ten states (Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, Indiana, Minnesota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah and Wisconsin).

As in the previous period, states continued to make good progress in increasing rates of vaccinations among older adults. Compared to the second half of February, 10 states increased their age 65+ vaccination rates by at least 0.5x, with Vermont more than doubling its vaccination rate for adults age 65+. Only a handful of states failed to make substantial progress in increasing vaccination rates among older adults. Though the 65+ vaccination rates in Louisiana and the District of Columbia appeared to have fallen in the first half of March, this was more than likely a statistical artifact rather than an actual decrease.

Percent of Adults Age 65+ Who Had Received a COVID-19 Vaccine

Notes about the Household Pulse Survey Data

The estimated rates presented in this post were calculated from the count estimates published by the Census Bureau. Though these counts are accompanied by standard errors, standard errors are not able to be accurately calculated for rate estimates. Therefore, we are not able to determine if the differences we found in our analysis are statistically significant or if the estimates themselves are statistically reliable. Estimates and differences for subpopulations at the state level should be assumed to have large confidence intervals around them and caution should be taken when drawing strong conclusions from this analysis. However, the fact that these early indications of COVID-19 inequities mirror patterns of other vaccinations inequities demonstrate reason for concern.

Though produced by the U.S. Census Bureau, the HPS is considered an “experimental” survey and does not necessarily meet the Census’s high standards for data quality and statistical reliability. For example, the survey has relatively low response rates (7.4% for March 3 - 15), and sampled individuals are contacted via email and text message, asking them to complete an internet-based survey. These issues in particular could be potential sources of bias but come with the tradeoffs of increased speed and flexibility in data collection as well as lower costs. A future post will investigate differences between COVID-19 vaccination rates estimated from survey data (such as the HPS) and administrative sources. The estimates presented in this post are based on responses from 78,306 adults. More information about the data and methods for the Household Pulse Survey can be found in a previous SHADAC blog post.

Previous Blogs in this Series

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update 3: 2/17 - 3/1) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update 2: 2/3 - 2/15) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (Update: 1/10 - 2/1) (SHADAC Blog)

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: New State-level and Subpopulation Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey (1/6 - 1/18) (SHADAC Blog)

Related Reading

State-level Flu Vaccination Rates among Key Population Subgroups (50-state profiles) (SHADAC Infographics)

50-State Infographics: A State-level Look at Flu Vaccination Rates among Key Population Subgroups (SHADAC Blog)

Anticipating COVID-19 Vaccination Challenges through Flu Vaccination Patterns (SHADAC Brief)

New Brief Examines Flu Vaccine Patterns as a Proxy for COVID – Anticipating and Addressing Coronavirus Vaccination Campaign Challenges at the National and State Level (SHADAC Blog)

Ensuring Equity: State Strategies for Monitoring COVID-19 Vaccination Rates by Race and Other Priority Populations (Expert Perspective for State Health & Value Strategies)

SHADAC Webinar - Anticipating COVID-19 Vaccination Challenges through Flu Vaccination Patterns (February 4th) (SHADAC Webinar)