Blog & News

What is Health Equity? — A SHADAC Basics Blog

October 28, 2024:

Basics Blog Introduction

SHADAC has created a series of “Basics Blogs” to familiarize readers with common terms, concepts, and topics that are frequently covered.

This Basics Blog will focus on the concept of health equity. We will answer and provide explanations for questions like:

- What is health equity?

- What is the definition of health equity?

- How can we talk about health equity in public health work?

- What are other supplemental terms and their definitions that are used in the health equity space?

With that foundation set, we then move into an example, using a study on provider discrimination data drawn from the Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) to understand how to apply a health equity lens to public health work and analysis. Finally, we end with some further thoughts and considerations on our evolving understand of this complex concept.

Keep on reading below to learn more about health equity.

Health Equity Definitions

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to advancing health equity and dismantling barriers in health care, defines health equity below:

It is important to note, though, that since health equity is conceptual, there is not a singular definition of it. This definition can also change and evolve, so it’s important to continue to educate yourself on health equity as time goes on.

What Is the Difference Between Equity and Equality?

While these two concepts are similar, equity and equality are not one in the same.

Equality is defined as giving the same treatment to everyone, regardless of individual needs or differences.

Equity is defined as giving treatment that is specific to individual needs, which allows everyone a fair chance at being successful.

The graphic below from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation provides a visual representation of the difference between equality and equity. In the ‘Equality’ example, all people are given the same mode of transportation – they are given equal treatment. However, because the individual’s needs are not considered, the outcome is not necessarily equal as can be seen in the visual. In the ‘Equity’ example, each individual is given a mode of transportation that works for their needs, leading to a more equitable outcome as can be seen in the example.

Source: Joan Barlow, “We Used Your Insights to Update Our Graphic on Equity” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, November 2022, We Used Your Insights to Update Our Graphic on Equity (rwjf.org). Reproduced with permission of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, N.J.

Additional Terminology Definitions

The topic of health equity is complex, with many factors feeding into it. To further understand health equity, it is important to define these additional factors and terms as well. While this list is not exhaustive, the terms below all refer to larger barriers and systems that must be addressed in order to reach equity in health and health care.

Health Disparities: Avoidable differences in health outcomes experienced by people with one characteristic (race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.) as compared to the socially dominant group (e.g., white, male, cis-gender, heterosexual, etc.).

Measuring disparities can benchmark progress toward achieving health equity.

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH): The daily context in which people live, work, play, pray, and age that affect health. SDOH encompass multiple levels of experience from social risk factors (such as socioeconomic status, education, and employment) to structural and environmental factors (such as structural racism and poverty created by economic, political, and social policies).

These factors are known quantities that contribute to social and health inequities.

Social Inequities: Differences between groups that are unfair, unjust, systemic, and avoidable. Social inequities can be characterized by race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, income, etc.

Social inequities can lead to poor health outcomes and further perpetuate systems and circumstances leading to health disparities (systemic racism, ableism, etc.).

Structural Racism: A complex system rooted in historical and current realities of differential access to power and opportunity for different racial groups. This system is embedded within and across laws, structures, and institutions in a society or organization. This includes laws, inherited disadvantages (e.g., the intergenerational impact of trauma) and advantages (e.g., intergenerational transfers of wealth), and standards and norms rooted in racism.

Structural racism contributes to a number of social determinants of health (SDOH). Public health systems must prioritize addressing structural racism as a primary barrier to health equity.

As you can see, many of these terms contribute to each other or are a result of another—truly showing how complex the topic of health equity is.

Using a Health Equity Lens on Provider Discrimination—Challenges and Interventions

Now that we have gone over some helpful terminology to keep in mind, let’s look at how to apply a health equity lens when looking at a real-life public health example.

The example we will go over in this section is related to LGBTQ+ health equity and discrimination. With roughly 13.9 million adults in the United States identifying as LGBTQ+, this example is both relevant and important for conversations on equity. Individuals of minoritized sexual orientation and gender identity have been historically marginalized, underrepresented in data, and faced with many health disparities, compared to their heterosexual, cisgender counterparts. These disparities exist for LGBTQ+ people not only at the national level, but also at the community, organizational, and smaller societal levels.

Thus, in June 2022, President Biden signed Executive Order 14075: Advancing Equality for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Individuals. This executive order is a sign of progress toward breaking down systemic barriers and more relatedly for this blog, empowering the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “promote the adoption of promising policies and practices to support health equity” for this population.

Now we will look specifically at a relevant measure from the Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) – provider discrimination by sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) in Minnesota – to demonstrate how we can perform studies, analyze results, and identify accessible solutions to health disparities by viewing them through a health equity lens.

The Data

Data coming from the 2021-2023 Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) reveals that among all adults in Minnesota, over half of the transgender/non-binary population (56.3%) reported experiencing Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity (SOGI) based discrimination from health care providers – significantly higher compared with cisgender adults’ reported experiences of discrimination (6.7%).

Nearly 9 in 10 transgender/non-binary adults (88.1%) and about one in four (24.1%) cisgender adults who identified as gay/lesbian reported discrimination. Two thirds of transgender/non-binary adults (66.1%) and about a quarter of cisgender adults (23.9%) that chose the ‘none of these’ option for sexual orientation also reported discrimination. Discrimination among people who identify as bisexual/pansexual is also high, and not statistically different for transgender/non-binary adults (40.5%) and cisgender adults (31.6%).

Experiencing discrimination has been shown to negatively affect both mental and physical health, as individuals and members of historically marginalized communities report worse health status and may forgo or delay care to avoid further discrimination.

Now, let’s look at potential ways to equitably address instances of provider discrimination by sexual orientation and gender identity at various levels.

Community Level

There are various ways to approach the issue of addressing provider discrimination. One potential solution is to make changes to education for the overall medical community, such as implementing cultural competency and communication training.

Cultural competency describes services, practices, and processes that are responsive to diverse practices, assets, needs, beliefs, and languages for an array of individuals and communities. Examples of incorporating cultural competence in health care include:

- Promoting awareness and knowledge

- Recognizing one’s biases

- Engaging in cultural competence & bias training

- Using accessible language

- Familiarizing oneself with the local community

- Recruiting diverse team members

Embracing these strategies can help immensely in understanding and reducing stigma as well as strengthening relationships between providers and the unique communities they serve.

Incorporating cultural competence into care can therefore offer meaningful ways to make strides toward reducing reported discrimination rates, such as those from individuals reporting SOGI-based provider discrimination in Minnesota. When cultural competence is practiced, better and more equitable health outcomes are observed for patients. Improved trust and communication between providers and patients can lead to more regular interactions with the health care system (like routine preventative visits), which can in turn lead to better treatments, health outcomes, and even better overall health status, another known issue for LGBTQ+ individuals.

Organizational Level

Addressing provider discrimination at a higher organizational level can be done through changing health systems and how they operate. Structural issues, such as payment/reimbursement structures, lack of time for visits, and workforce diversity may also contribute to the discrimination felt by different individuals.

Structural competency, which is the belief that inequalities in health must be conceptualized in relation to the institutions and social conditions that determine health related resources, can then play a crucial role in promoting equitable care alongside cultural competency by addressing issues at a structural level. This concept can be implemented in health systems through training in five core competencies:

- Recognizing the structures that shape clinical interactions

- Developing an extra-clinical language of structure

- Rearticulating “cultural” formations in structural terms

- Observing and imagining structural interventions

- Developing structural humility

Structural training and education helps medical professionals more effectively understand the economic and social determinants of health (SDOH) that occur for their patients before any interaction with the health care system occurs. In the instance of individuals belonging to the LGBTQ+ community, these can take the shape of lack of health insurance coverage or access barriers. Additionally, organizations can invest in structural changes to advance health equity through improved data systems that are able to track populations’ diverse makeup (race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, primary language), alongside SDOH (income, education, employment) and health needs (utilization of care, treatment, and health outcomes), to better understand who they are serving and how to improve services.

Societal Level

On a larger scale, the state of Minnesota has made it a goal to ensure all Minnesotans receive high quality health care, free of provider or system bias.

Citing the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) data on responses to unfair treatment, the Minnesota Department of Health (DHS) recognized the disparity between the higher rates of unfair treatment by Black Minnesotans (39%) and Transgender Minnesotans (50%) compared to White Minnesotans and cis-gendered men (9% and 12%, respectively), and created a measurable goal to directly address this issue.

By 2027, MN DHS states that it hopes to reduce the percentage of transgender and non-binary Minnesotans and Black Minnesotans reporting unfair treatment by their providers by 50%. This goal is a meaningful step toward health equity for individuals with different racial and ethnic backgrounds and different gender identities.

Shifting Definitions and Future Considerations

In the example above, examining reported rates of provider discrimination in Minnesota and potential solutions at different levels helps to understand not only a practical example of how better understanding of health equity and systemic issues can clarify what the major barriers to advancing equity look like, but also how they can be addressed.

Even now as the definition of health equity is not set in stone and continues to evolve, we see opportunity for solutions to advance health equity--both in general, and for people with minoritized sexual and gender identities--to evolve as well. However, this does not apply only to health equity, as the definitions and understanding of many of the terms described above have evolved over time. As society and demographics continue to shift, so does our insight and understanding of these concepts.

There is a need for more involvement at the community, organizational, and societal level in advancing health equity. While there is progress in the right direction, there are still structural barriers that need to be overcome and met with applicable solutions that lead to positive systemic change.

Interested in learning more about health equity? Now that you have the SHADAC Basics down, try some of the following resources to continue to expand your knowledge:

Blog & News

Provider Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity: Experiences of Transgender/Nonbinary Adults and Sexually Minoritized Adults in Minnesota

September 03, 2024:Background

Understanding the experiences of people with minoritized sexual and gender identities matters for public health. Compared with straight and cisgender adults, these populations face inequitable barriers to health care access1,2 and disparities in health outcomes, including mental and physical health, activity limitations, and chronic conditions.3,4 Accordingly, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) data collection is foundational in advancing population health and health equity in order to better understand the disparities and inequities these populations face.

As highlighted in our previous blogs, one focused on populations by sexual orientation and the other focused on populations by gender identity, reports of discrimination from health care providers based on sexual orientation or gender identity are high among people with minoritized sexual and gender identities. This discrimination is associated with barriers to health care access. For example, individuals who report discrimination may not receive proper treatment from discriminatory providers, and they may forgo or delay health care to avoid discrimination. Across populations, experiencing discrimination has been shown to negatively affect mental and physical health.5

In this blog, we build on these results by pooling two years of data to look at people’s experiences at the intersection of minoritized sexual and gender identities in reports of provider discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation. We used a survey question asking, ‘how often their gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression cause health care providers to treat them unfairly.’ Our analysis also illustrates how the commonly used measures for sexual orientation do not adequately encompass the range of options for sexually minoritized people, and how these limitations disproportionately impact the transgender and nonbinary populations.

Study Approach

We used 2021-2023 data from the biennial Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA). See Methods here.

Results

Among all adults in Minnesota, over half of the transgender/nonbinary population (56.3%) reported experiencing provider discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity – significantly higher compared with cisgender adults’ reported experiences of discrimination (6.7%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Rates of SOGI-Based Provider Discrimination by Sexual Orientation Among Cisgender Adults and Transgender/Nonbinary Adults in Minnesota, 2021-2023.

| Cisgender | Transgender/Nonbinary | ||

| All Adults (18+) | 6.7% | 56.3% | * |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Straight | 4.9% | -- | -- |

| Gay or Lesbian | 24.1% | 88.1% | * |

| Bisexual or Pansexual | 31.6% | 40.5% | |

| None of These | 23.9%† | 66.2% | * |

* Significant difference between cisgender and transgender/nonbinary adults in reports of provider discrimination.

† Estimate may be unreliable due to limited data (relative standard error greater than or equal to 30%).

-- Estimate not available to limited data.

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021-2023 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

When delving into experiences of provider discrimination among people with diverse gender and sexual identities, we found that reports of provider discrimination from transgender/nonbinary adults who identified as gay/lesbian or ‘none of these’ were significantly higher than for cisgender adults who identify as gay/lesbian or ‘none of these.’

Specifically, provider discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation was reported by:

- Nearly 9 in 10 transgender/nonbinary adults (88.1%) and about one in four (24.1%) cisgender adults who identified as gay/lesbian

- Two thirds of transgender/nonbinary adults (66.1%) and about a quarter of cisgender adults (23.9%) that chose the ‘none of these’ option for sexual orientation

Provider discrimination was also high for people who identified as bisexual/pansexual, and, for this group, not significantly different for transgender/nonbinary adults (40.5%) and cisgender adults (31.6%).

The lowest rates of provider discrimination were reported by straight cisgender adults at 4.9%.

Please note that sample sizes were limited, particularly for comparing straight or bisexual/pansexual adults by gender.

Discussion

Consistently across sexual orientations, reports of provider discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation were higher for transgender/nonbinary adults compared with cisgender adults. This suggests that discrimination associated with sexual minoritization may disproportionately impact transgender/nonbinary populations.

Individuals that experience multiple minoritized identities must contend with discrimination on multiple levels. For example, someone may experience discrimination based on a combination of their sexual orientation, gender identity, race, and/or disability status. Looking at the data from this study, we can illustrate this idea looking at provider discrimination reported by gay/lesbian cisgender adults and gay/lesbian transgender/nonbinary adults. Both of these groups share the same sexual orientation, but differ in gender identity. The group with multiple minoritized identities, the gay/lesbian transgender/nonbinary group, reported significantly higher rates of discrimination (88.1%) compared to cisgender gay/lesbian adults (24.1%), which may be related to their multiple levels of marginalization.

Overall, though, our analysis finds that discrimination remains alarmingly high across all groups of people with minoritized sexual and/or gender identities. Looking across the Minnesota population, this study documents provider discrimination among both transgender/nonbinary and cisgender sexual minorities, including people who identify as gay/lesbian, bisexual/pansexual, or ‘none of these.’

Our study also shows the importance of providing data for groups outside of the largest categories such straight, gay/lesbian, or bisexual. For example, by pooling multiple years of data, we were able to produce estimates for gender and sexual minorities including people who responded ‘none of these’ for sexual orientation. This latter group is important to highlight considering the wide range of sexual identities beyond gay/lesbian, straight, and bisexual. Reports of discrimination were high for both transgender/nonbinary and cisgender people who responded ‘none of these’ for sexual orientation, and significantly higher for the transgender/nonbinary people compared with cisgender.

This study highlights continued evidence of health care provider discrimination in Minnesota, with transgender/nonbinary sexual minorities being particularly impacted. Policies are urgently needed to address this discrimination, particularly for transgender/nonbinary Minnesotans who already face barriers to health care access and disparities in health outcomes compared to cisgender adults.

METHODS

Data

The 2021-2023 Minnesota Health Access (MNHA) survey is a biennial population-based survey on health insurance coverage and access conducted in collaboration with the Minnesota Department of Health. We limited the analysis to adults responding for themselves about experiences of discrimination (n=17,828), and we excluded proxy reports (e.g., a household member answering for a spouse or roommate).

Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the MNHA Survey

To study discrimination, we looked at a survey question that asks respondents ‘how often their gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression cause health care providers to treat them unfairly.’ Responses of ‘never’ were coded as no discrimination, and responses of ‘always,’ ‘usually,’ or ‘sometimes’ were coded as discrimination.

Sexual Orientation Measures in the MNHA Survey

Similar to other surveys that collect sexual orientation data, the MNHA asks about sexual orientation using three main response options: ‘gay or lesbian’; ‘straight, that is, not gay or lesbian’; and, ‘bisexual or pansexual.’ Survey respondents could also select ‘don’t know’ or ‘none of these,’ with an option to write in their own answer. We reviewed write-in responses and, when possible, recoded these responses to align with the existing categories.

Recoding write-in responses was a key step in reducing the risk of misclassification in order to include people who selected ‘none of these’ for sexual orientation in analysis. Some straight adults are unfamiliar with terminology for sexual orientation, which can lead to inaccurate responses.6 We reclassified inappropriate write-in answers (such as man, woman, married, or offensive comments) as ‘refused.’

After this step in cleaning the data, we tabulated results separately for two groups: people who responded ‘none of these’ with no write-in, and those who responded ‘none of these’ with an LGBTQ+ write-in response such as ‘queer’ or ‘asexual.’ Rates were similar, which helped to justify combining these subgroups into a single ‘none of these’ variable to improve sample size and produce estimates of reported discrimination for this subpopulation.

MNHA measures of sexual orientation were generally consistent with current best practices (for more information on SOGI data collection practices in Medicaid click here, and click here for our brief on federal survey sample size analysis), our analysis highlights some limitations of commonly used survey measures for sexual orientation. A small difference in the MNHA from typical measures is the inclusion of ‘bisexual or pansexual’ rather than only ‘bisexual’ as a response option. Current recommendations suggest using the phrasing, ‘I use a different term,’ rather than ‘none of these’ as a response option.7

Gender Identity Measures in the MNHA Survey

In 2023, the MNHA switched from a single question measuring gender to a two-step question asking first, ‘how do you describe your gender,’ and second, ‘are you transgender.’ As described in a previous blog, this approach was developed by the Oregon Health Authority through extensive community engagement and has advantages of being clear and inclusive.8 Response options for gender were:

- Man

- Woman

- Gender non-binary or two-spirit

- Agender/no gender

- Another gender (optional write in response)

In contrast, 2021 response options included ‘transmale/transman’ and ‘transfemale/transwoman’ listed after ‘male/man’ and ‘female/woman,’. Although current best practice recommendations for federal surveys list ‘transgender’ as response option after male/female, this approach has the limitation of implying that being transgender is ‘other’ and mutually exclusive from male/female. Similarly, the two-step question currently recommended for federal surveys asks about ‘sex assigned at birth,’ which may be perceived as invalidating and adds cognitive burden, especially for people with low literacy. Using accessible language in survey questions supports user experiences and overall response rates, and helps to reduce data quality problems such as item non-response and misclassifications. Guidance developed by the state of Oregon offers an inclusive approach to measuring gender on population surveys.

Analysis

We tabulated gender and sexual orientation based discrimination by sexual orientation for cisgender and transgender/nonbinary adults in Minnesota. For transparency, we present results for all response categories, even if estimates must be suppressed due to lack of data. Tests for statistical significance were conducted at the 95% confidence level.

References

[1] Bosworth, A., Turrini, G., Pyda, S., Strickland, K., Chappel, A., De Lew, N., Sommers, B.D.. (June 2021). Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care for LGBTQ+ Individuals: Current Trends and Key Challenges. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-07/lgbt-health-ib.pdf

[2] Kates, J., & Ranji, U. (2024). Health Care Access and Coverage for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community in the United States: Opportunities and Challenges in a New Era. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/perspective/health-care-access-and-coverage-for-the-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-lgbt-community-in-the-united-states-opportunities-and-challenges-in-a-new-era/

[3] Baptiste-Roberts, K., Oranuba, E., Werts, N., & Edwards, L. V. (2017). Addressing health care disparities among sexual minorities. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics, 44(1), 71-80.

[4] Feir, D., & Mann, S. (2024). Temporal Trends in Mental Health in the United States by Gender Identity, 2014–2021. American Journal of Public Health, (0), e1-e4.

[5] Pascoe, E. A., & Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 135(4), 531.

[6] Miller, K., & Ryan, J. M. (2011). Design, development and testing of the NHIS sexual identity question. National Center for Health Statistics, 1-33.

[7] Office of the Chief Statistician of the United States. (n.d.). Recommendations on the Best Practices for the Collection of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data on Federal Statistical Surveys. (Washington, D.C.) https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/SOGI-Best-Practices.pdf

[8] Oregon Health Authority. (2021, December 21). OHA/ODHS SOGI Committee Structure and Process used to Develop SOGI Data Recommendations (December 2021). https://www.oregon.gov/oha/EI/Documents/SOGI-Data-Committee-Survey.pdf

SHADAC Expertise

MINNESOTA HEALTH ACCESS SURVEY

Overview of the MNHA Survey

The Minnesota Health Access (MNHA) survey is a statewide web and telephone survey that collects information on how people access health care and health insurance coverage in Minnesota. The survey dates back to 1990 and has been conducted biennially in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Health's Health Economics Program since 2001. The data collected are used to monitor rates of insurance coverage and uninsurance across different groups of Minnesotans (geographic, income, ethnicity, etc), and experiences using care to determine specific barriers to insurance and health care services. It is used to inform policy that can help improve health care access for all Minnesotans.

Historical Context

The MNHA was first funded in 1990 to provide a state-specific rate of uninsurance at the time of the survey; this point-in-time estimate was not available through any federal data sources until 2007. The MNHA data is credited with informing sweeping bipartisan health care reform in the early 1990s - known as MinnesotaCare - and continues to directly inform health policy to this day.

SHADAC’s Kathleen Call first got involved with the survey in 1995. Call quickly learned the value of the data because analysts at the Minnesota Department of Health and the Minnesota Department of Human Services requested access to the data (without identifiers) for fiscal notes and policy analyses. This was the start of a great partnership. State staff asked hard questions about the veracity of the insurance estimates, which eventually inspired a line of research exploring the accuracy of health insurance reporting in surveys and potential bias to uninsurance estimates. The findings consistently support confidence in using insurance coverage estimates from survey data to monitor and inform health policy. Beginning in 2001, Call and staff from MDH’s Health Economics Program worked together to fund the MNHA. This early collaboration led to a formal partnership and MNHA funding through the legislature, which began in 2007. MNHA also provides rich data around health care experiences and inequities, including the impact of insurance-based, race-based and gender-based discrimination on access to health care services.

What's Ahead

The biennial MNHA also spurred several follow-up surveys. The first was the Minnesota Health Insurance Transitions Study (MH-HITS), a follow-up telephone survey of children and adults in Minnesota who had no health insurance in the fall of 2013 to examine gains in coverage in 2014; 1 year after passage of the Affordable Care Act. Most recently, willing participants from the 2021 MNHA completed the 2023 Minnesota Telehealth and Access Survey (MNTAS) that focused on health care experience and access, particularly related to telehealth. MNTAS findings will be shared as they become available. Beginning in 2023, MNHA participants are invited to join the Minnesota Voices on Health Panel (MNVoices). This panel provides an opportunity to conduct short policy focused follow-up surveys and to look at patterns over time.

Read more about the survey or check out SHADAC products that use MNHA data:

- - Minnesota Health Access Survey 2021 Technical Report

- - Learn More About Past Survey Data

- - Examining Discrimination and Health Care Access by Sexual Orientation in Minnesota

- - Examining Gender-Based Discrimination in Health Care Access by Gender Identity in Minnesota

- - MNHA Data Show Minimal Impact from COVID Pandemic on 2020 Insurance Coverage

- - Minnesota’s uninsured rate hit historic low in 2021 but racial disparities increased (MDH Cross Post)

- - Insurance-Based Discrimination Reports and Access to Care Among Nonelderly US Adults, 2011–2019

Publication

Minnesota Health Access Survey 2021 Technical Report

This report describes the Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) data collection process and methodology, emphasizing the most recent administration of the survey completed in 2021. The 2021 MNHA represents the first time using a single address based (ABS) frame.

Overview of MNHA

The Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) is a biennial survey of non-institutionalized Minnesota residents. The survey collects detailed information on health insurance coverage options, access to coverage and health care services, and basic demographic data. The goal of the survey is to document trends in health insurance coverage, and access to insurance and health care at the state and regional level, as well as for select subpopulations (e.g., rural, low-income families, populations of color and American Indians). The MNHA represents a partnership between the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) Health Economics Program and the University of Minnesota’s State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC).

The MNHA data play an important role in monitoring trends in health insurance coverage, evaluating and informing health policy development in Minnesota on topics such as affordability of coverage, access to healthcare, and redesign of public program coverage. The MNHA provides precise and timely estimates on a range of coverage and access relevant questions, is adaptable and responsive to developing state health policy issues, and ensures the availability of micro-data for time sensitive research and policy analysis.

The MNHA has been conducted a number of times over the years: in 1990, 1995, 1999, 2001, 2004, and every two years beginning in 2007.1 This technical report focuses primarily on the 2021 MNHA, providing some cumulative data in table form.2

1 Beginning in 2007, MNHA funding is from a legislative appropriation to the Minnesota Department of Health and additional support from the Minnesota Department of Human Services since 2011.

2 For information about earlier versions of the MNHA contact Kathleen Thiede Call at callx001@umn.edu and the Health Economics Program at health.mnha@state.mn.us.

Blog & News

Examining Discrimination and Health Care Access by Sexual Orientation in Minnesota

March 22, 2023:Authors: Natalie Mac Arthur, Jeremy Duval, Kathleen Call

|

More than one-third of lesbian/gay adults in Minnesota reported experiencing discrimination from health care providers based on their sexual orientation and gender identity. |

Survey Question OverviewIn this analysis, we examined the experiences of adults in Minnesota by sexual orientation using data from the biennial 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA). The MNHA asked respondents how often their gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression cause health care providers to treat them unfairly. In addition to this measure of SOGI-based discrimination, this survey includes information on access to health care such as forgone care due to costs. |

Introduction

Discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) from health care providers is a barrier to creating an equitable health care system. Nearly one in five lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LBGTQ) adults reports avoiding health care due to anticipated discrimination (Casey et al., 2019). Compared with straight adults, lesbian/gay and bisexual adults are more likely to forgo or delay health care (Jackson et al., 2016, Nguyen et al., 2018). However, less is known about the association between reports of SOGI-based discrimination from health care providers and health care access.

We included three sexual orientation categories in this study: straight, lesbian/gay, and bisexual/pansexual. Survey respondents also had the option to select “none of these” and write in their own response. Due to sample size limitations, we excluded observations with responses that we could not recode to the existing categories. We tabulated SOGI-based discrimination and four measures of health care access by sexual orientation for adults in Minnesota. We also examined differences in health care access for respondents who did and did not report discrimination.

Results

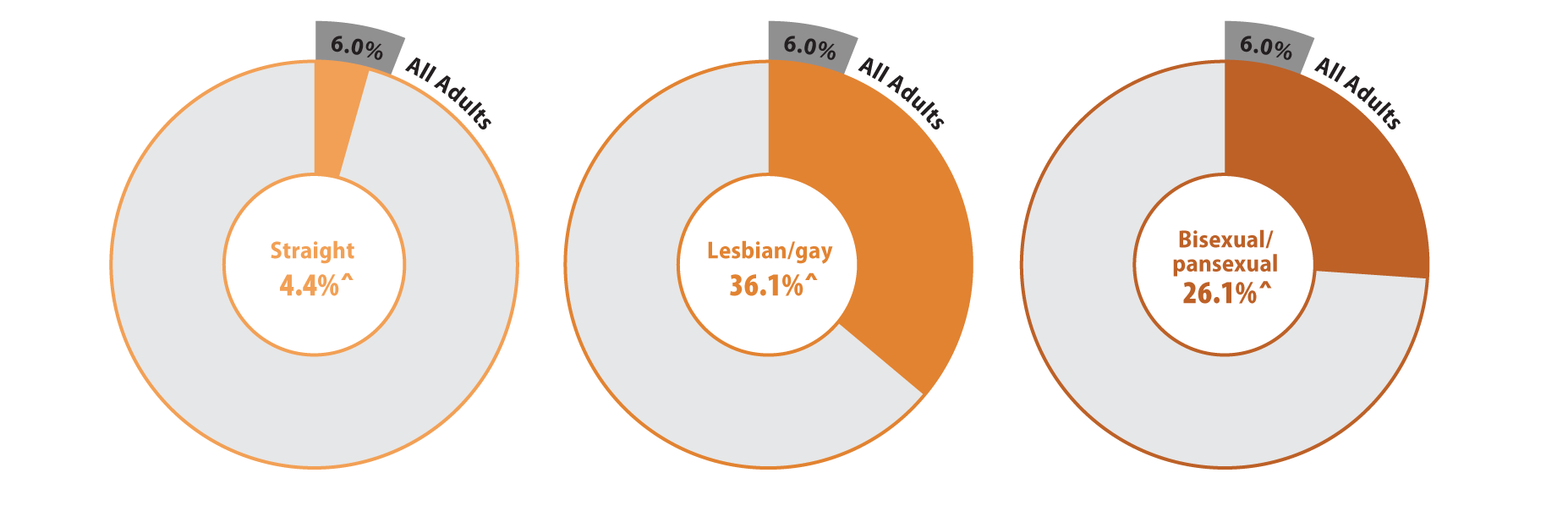

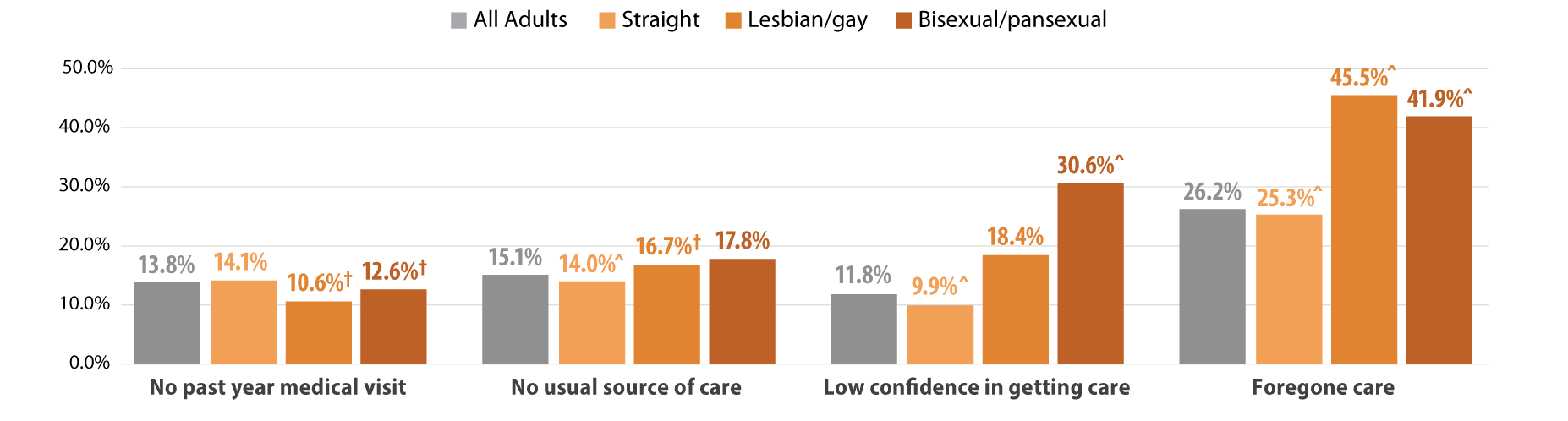

Reports of discrimination from health care providers based on SOGI were significantly higher among lesbian/gay (36.1%) and bisexual/pansexual (26.1%) populations compared with the state average of 6% (Figure 1). Sexual minorities were also more likely to report barriers to health care access when compared with all adults in Minnesota (Figure 2). Low confidence in getting needed health care was significantly above the state average (11.8%) for people who identify as bisexual/pansexual (30.6%). Statewide, over a quarter of adults reported forgone care due to costs (26.2%), which included routine medical care, prescription drugs, dental care, specialists, and mental health care. Rates of forgone care were significantly higher for people who identify as lesbian/gay (45.5%) or bisexual/pansexual (41.9%).

Figure 1. Unfair treatment from health care providers based on gender or sexual orientation in Minnesota

^ Rate significantly different from All Adults at the 95% confidence level.

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

Figure 2. Health care access and barriers to care

^ Rate significantly different from All Adults at the 95% confidence level.

† Estimate may be unreliable due to limited data (relative standard error greater than or equal to 30%).

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

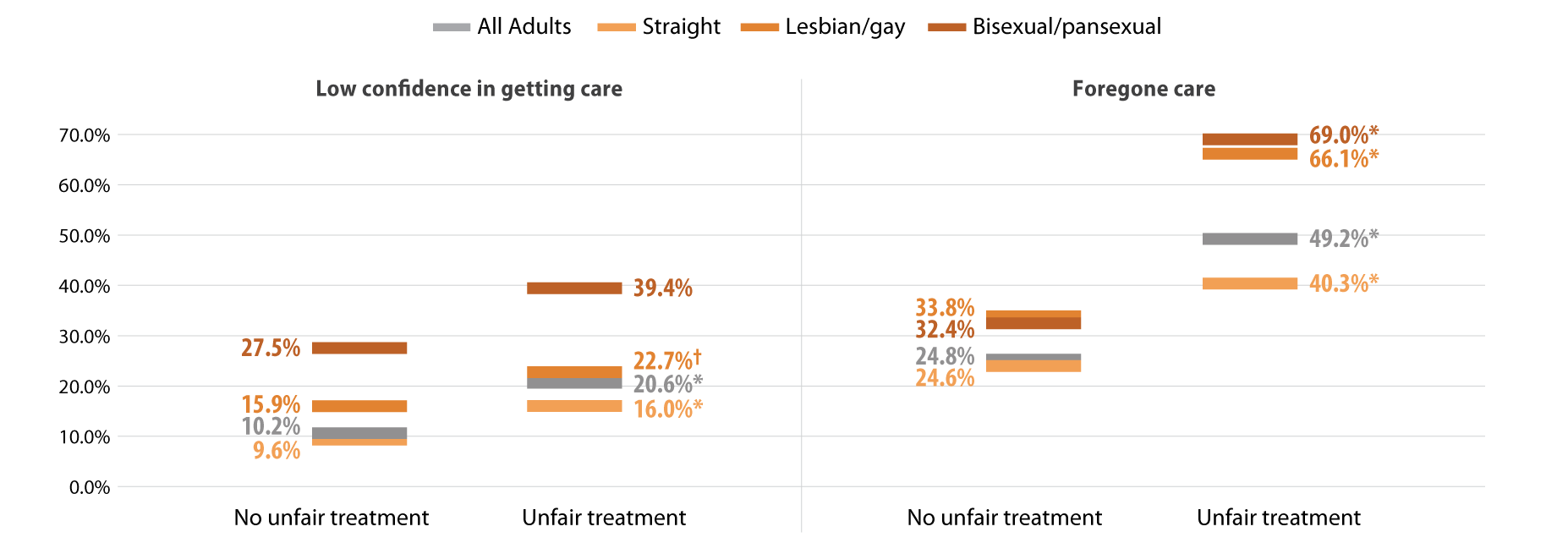

We found that Minnesotans who experienced SOGI-based discrimination were more likely to have low confidence in getting care and forgone care compared to those who did not experience discrimination (Figure 3). People who experienced discrimination had elevated barriers across all population groups including people identifying as straight, lesbian/gay, or bisexual/pansexual. However, low confidence in care was highest among bisexual/pansexual adults who reported SOGI-based discrimination (39.4%). Half of all adults with SOGI-based discrimination reported forgone care due to costs, while about two-thirds of bisexual/pansexual (69.0%) and lesbian/gay (66.1%) adults who reported SOGI-based discrimination had forgone care.

Figure 3. Experiences of gender-based discrimination associated with barriers to health care access

* Significant difference within a given subpopulation between rates of people who experienced unfair treatment and those who did not.

† Estimate may be unreliable due to limited data (relative standard error greater than or equal to 30%).

Source: SHADAC analysis of the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey.

Discussion

MethodsData are from the 2021 Minnesota Health Access (MNHA) survey, which is a biennial population-based survey on health insurance coverage and access conducted in collaboration with the Minnesota Department of Health. We limited the analysis to adults responding for themselves about experiences of discrimination and access (n=10,003); we excluded proxy reports (e.g., a household member answering for a spouse or roommate). Tests for statistical significance were conducted at the 95% confidence level. |

Within the health care setting, discrimination based on SOGI was prevalent among lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual adults. SOGI-based discrimination from health care providers was reported by over a third of lesbian/gay adults in Minnesota and over a quarter of bisexual/pansexual adults. Barriers to health care access, including low confidence in getting care and forgone care, were also high among lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual adults compared with the average rates seen among adults in Minnesota. Further, reports of SOGI-based discrimination correlated with even higher rates of barriers to access among lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual adults; a majority of these populations who reported discrimination also had forgone health care due to costs.

Discrimination by health care providers has substantial clinical implications. Across populations, discrimination negatively affects mental and physical health (Pascoe and Richman, 2009). Compared with straight adults, lesbian/gay and bisexual adults experience health disparities including mental and physical health, activity limitations, and chronic conditions (Gonzales and Henning-Smith, 2017). For LBGTQ adults, both discrimination and barriers to health care are associated with worse mental health, behavioral health, and health-related quality of life (Lee 2016 et al., Jung et al., 2023). One recent study suggests that delayed health care partially mediates the connection between discrimination and worse health status among LBGTQ women (Scott et al., 2022). Our work contributes evidence linking provider discrimination to forgone health care and lack of confidence in getting care.

The clinical impact of discrimination is likely to vary across the life course and across the spectrum of intersectional identities including LBGTQ and race/ethnicity. Compared with lesbians, bisexual women are more likely to report poor physical and mental health and disabilities; both groups of women face higher risks than straight women (Fredriksen-Goldsen 2023). Gay Black and Hispanic men face greater barriers to health care access than gay white men (Hsieh et al., 2017). Among older adults, one survey found that nearly four out of five LBGTQ people anticipate encountering discrimination in long-term care services (Dickson et al., 2022).

Differences in health care access and socioeconomic resources may exacerbate the influence of provider discrimination on health outcomes. Although studies have found that delays in health care among lesbian/gay and bisexual adults persist even with insurance coverage, their coverage may not provide comparable affordability of health care relative to straight adults (Jackson et al., 2016, Nguyen et al., 2018,Tabaac et al., 2020). Lesbian/gay and bisexual adults are less likely to have private coverage and more likely to have purchased a plan from the individual market, which may have higher premiums and deductibles. Furthermore, they are also more likely to experience lapses in coverage. These studies indicate that both cost concerns and previous bad health care experiences contribute to delays in care. Our results add to the growing body of literature documenting high rates of forgone care due to cost for lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual adults. Additionally, we document lack of confidence in getting health care among these populations and greater barriers to access among those who reported SOGI-based discrimination from a health care provider.

Conclusion

Reports of discrimination among lesbian/gay and bisexual/pansexual Minnesotans are troubling and require a response. The Affordable Care Act, which expanded Medicaid in willing states, also expanded non-discrimination protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity (KFF, 2014). However, these protections are limited in promoting health care access. Relative to other states, Minnesota offers a robust Medicaid program. Barriers to access may be even higher for LBGTQ people in states that did not expand Medicaid and states with fewer protective non-discrimination laws. Socioeconomic policies at the federal and state level are important for addressing gaps in health equity for many members of the LBGTQ community.

Greater availability of data including SOGI measures would strengthen efforts to better understand and address the health care needs of LBGTQ populations (SHADAC, 2021). Direct measures of discrimination are also important to monitor progress in providing equitable access to health care services (Lett et al., 2022). Ongoing research is needed to improve health equity and address barriers to health care for LBGTQ populations.

Check out our companion blog "Examining Gender-Based Discrimination in Health Care Access by Gender Identity in Minnesota".

References

Casey, L. S., Reisner, S. L., Findling, M. G., Blendon, R. J., Benson, J. M., Sayde, J. M., & Miller, C. (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health services research, 54 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 1454–1466. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13229

Dickson, L., Bunting, S., Nanna, A., Taylor, M., Spencer, M., & Hein, L. (2022). Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Adults’ experiences with discrimination and impacts on expectations for long-term care: Results of a survey in the southern United States. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(3), 650-660.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Romanelli, M., Jung, H. H., & Kim, H. J. (2022). Health, economic, and social disparities among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Sexually Diverse Adults: Results from a population-based study. Behavioral Medicine, 1-12.

Gonzales, G., & Henning-Smith, C. (2017). Health disparities by sexual orientation: results and implications from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Journal of Community Health, 42, 1163-1172.

Jackson, C. L., Agénor, M., Johnson, D. A., Austin, S. B., & Kawachi, I. (2016). Sexual orientation identity disparities in health behaviors, outcomes, and services use among men and women in the United States: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 807. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3467-1

Kates, J., & Ranji, U. (2014, February 21). Health Care Access and Coverage for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community in the United States: Opportunities and Challenges in a New Era. KFF. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/perspective/health-care-access-and-coverage-for-the-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-lgbt-community-in-the-united-states-opportunities-and-challenges-in-a-new-era/

Lett E., Asabor E., Beltrán S., Cannon A.M., Arah O.A. (2022). Conceptualizing, Contextualizing, and Operationalizing Race in Quantitative Health Sciences Research. Ann Fam Med 20(2):157-163. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2792

Nguyen, K. H., Trivedi, A. N., & Shireman, T. I. (2018). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults report continued problems affording care despite coverage gains. Health Affairs, 37(8), 1306-1312.

Pascoe, E. A., & Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 135(4), 531.

Scott, S. B., Knopp, K., Yang, J. P., Do, Q. A., & Gaska, K. A. (2022). Sexual minority women, health care discrimination, and poor health outcomes: A mediation model through delayed care. LGBT Health. http://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2021.0414

SHADAC. (2021, October). A New Brief Examines the Collection of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) Data at the Federal Level and in Medicaid. https://www.shadac.org/news/new-brief-examines-collection-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-sogi-data-federal-level

Tabaac, A. R., Solazzo, A. L., Gordon, A. R., Austin, S. B., Guss, C., & Charlton, B. M. (2020). Sexual orientation-related disparities in health care access in three cohorts of US adults. Preventive Medicine, 132, 105999.