Include Social and Economic Factors

Blog & News

Food Insecurity in America: New Social Determinants State Health Compare Measure Tracks Percent of Households Experiencing Food Insecurity

January 03, 2025:Social determinants of health are social factors that impact an individual or community’s health. As explained by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, “Good health begins where we live, learn, work and play. Stable housing, quality schools, access to good jobs, and neighborhood safety are all important influences, as is culturally competent health care.”

Access to food, nutritious and varied, is also considered a social determinant of health.1 Numerous studies have shown that food insecurity, aka having limited or unstable access to food, is linked to poorer health outcomes, higher chronic disease prevalence, and overall financial hardship.

Newly added to SHADAC’s State Health Compare tool, our ‘Food Insecurity’ measure provides state-level estimates of the prevalence of household-level food insecurity by state and by a number of breakdowns. In this post, we will review a food insecurity definition, the details of SHADAC’s food insecurity measure, and some food insecurity statistics & data highlights from that measure.

What Is Food Insecurity?

As we stated earlier, a general food insecurity definition is when an individual or household has limited or unstable access to food. There are specific definitions, though, that the USDA Economic Research Service follows, which informed SHADAC’s Food Insecurity Measure on State Health Compare.

The USDA Economic Research Service defines a food insecure household as a household that, at times during the year, was “uncertain of having or unable to acquire enough food to meet the needs of all their members because they had insufficient money or other resources for food.”2

Further, a household is designated as ‘low food security’ by the USDA if they reported reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet with little or no indication of reduced food intake; the USDA designates a household as ‘very low food security’ if they reported multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.2

The food insecurity estimates presented on State Health Compare indicate the percentage of households experiencing food insecurity defined as those experiencing either low or very low food security.

SHADAC’s Food Insecurity Measure on State Health Compare

State Health Compare is SHADAC’s online, interactive data tool providing data visualizations, tables, and data sets of state-level health estimates on a variety of measures, including measures on:

- Access to Care (e.g., Had usual source of medical care, broadband internet access, etc.)

- Cost of Care (e.g., People with high medical cost burden, forgone care, etc.)

- Health Outcomes (e.g., suicide deaths, chronic disease prevalence, etc.)

- Social and Economic Factors (e.g., adverse childhood experiences, etc.)

The new “Food Insecurity” measure falls under the ‘Social and Economic Factors’ category. Data for this measure is available for 2011 – 2022, produced using the Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement (CPS-FSS).

We have also added a number of breakdowns to this measure to allow for further analysis and disaggregation. The Food Insecurity measure is available by the following breakdowns, shown in Table 1:

Table 1. Available Breakdowns and Time Frames for Food Insecurity Measure on SHC

Accessible version of Table 1 found in "Accessible Tables" section in Conclusion.

Now that we have gone over the available data and breakdowns for this measure, let’s take a look at a few food insecurity statistics and data highlights straight from State Health Compare.

Food Insecurity in America: Data Highlights from State Health Compare

Nationwide, 11.2% of households experienced food insecurity in 2020-2022. During this same time frame, food insecurity ranged from as high as 16.6% of households in Arkansas, to as low as 6.2% of households in New Hampshire.

Food Insecurity Over Time: Vast Majority of States Have Seen Decreased Food Insecurity Rates

When we examine food insecurity over time, we can see that the vast majority of states have experienced a statistically significant decrease in food insecurity between 2011 – 2013 and 2020 – 2022.

Figure 1. Change in Percentage of Food Insecure Households by State Between 2011 and 2022

Figure 1 shows the changes in food insecurity for the full range of time available on State Health Compare. When comparing the 2020 – 2022 time frame to the 2011 – 2013 time frame, the majority of states (40) saw statistically significant decreases in the percent of households experiencing food insecurity.

The largest decrease was in North Carolina, which was down 6.6 Percentage Points (PP). The smallest statistically significant decrease was in Pennsylvania, which was down 1.8 PP.

South Carolina was the only state to experience an increase in food insecurity between these two time frames (statistically significant or not) with an increase of 0.4 PP.

Food Insecurity by Race / Ethnicity: African-American / Black Households Experienced the Highest Levels of Food Insecurity

As we saw in the previous section, most states had significant decreases in rates of food insecure households over time. However, when we break down this data by race/ethnicity, disparities in food insecurity levels are revealed.

Table 2. Five States and Racial/Ethnic Groups with the Highest and Lowest Percentages of Food Insecurity, 2020 - 2022

Accessible version of Table 2 found in "Accessible Tables" section in Conclusion.

Table 2 shows the five highest and lowest rates of insecurity for any race/ethnicity in the 2018 – 2022 time frame, which reveals that food insecurity varied greatly by race/ethnicity.

Across the country and by race, the lowest rate of food insecurity in 2018-2022 was 1.3% for White individuals in the District of Columbia, while the highest rate was 29.0% for Black individuals in North Dakota. Food insecurity prevalence was generally highest for African American/Black households, with the lowest rate of household level food insecurity for African American/Black households in any state, in Massachusetts at 14.2%, still being higher than the highest rate for White households in any state, in West Virginia at 14.1%.

Food Insecurity by Presence of Children in Household: Those with Children Experienced Higher Levels of Food Insecurity

Figure 2 presents the prevalence of household level food insecurity by presence of child in the household.

Figure 2. Change in Percentage of Food Insecure Households by State and by Presence of Children in Household Between 2020 and 2022

During the 2020 – 2022 time frame, households in almost every state that included children experienced food insecurity at higher rates than households in the same state without children.

The exceptions to this were Colorado, Connecticut, Vermont, and West Virginia, which saw more households without children experiencing food insecurity compared to those with children.

The greatest difference in food insecurity between these two groups (households with and without children) was in Delaware (11.3 PP), while the smallest difference was in Connecticut (0.3 PP).

Conclusion

As we can see just from using State Health Compare, many factors can, and do, influence levels of food insecurity. Household makeup, the state you live in, and current events in time can all impact the stability and availability of food to different populations and families. Continued research into what impacts levels of food insecurity can hopefully help us identify where supports are needed, and what kind of actions would be most effective and efficient at providing people with stable and accessible food, care, and support.

You can get started on this important research yourself by exploring and using State Health Compare. Build data tables, visualizations, and more on a number of health care and public health related measures on our simple and easy to use site.

We’d love to hear what you discover on State Health Compare – tag us on LinkedIn, or send us an email with comments or questions at shadac@umn.edu.

Notes and Citations

1. NAMI, Social Determinants of Health: Food Security

2. USDA ERS - Key Statistics & Graphic

Accessible Tables

Table 1. Available Breakdowns and Time Frames for Food Insecurity Measure on SHC

|

Breakdown |

Subgroups |

Available Time Frames |

|---|---|---|

|

Total |

N/A |

2011 – 2013 2014 – 2016 2017 – 2019 2020 – 2022 |

|

Race/ethnicity |

Hispanic/Latino White African-American/Black Asian/Pacific Islander Other/Multiple Races |

2013 – 2017 2018 – 2022 |

|

Presence of Child in Household |

Child in household No child in household |

2011 – 2013 2014 – 2016 2017 – 2019 2020 – 2022 |

Table 2. Five States and Racial/Ethnic Groups with the Highest and Lowest Percentages of Food Insecurity, 2020 - 2022

Highest Food Insecurity Prevalence by State and Race/Ethnicity

|

State |

Race/Ethnicity |

Food Insecurity Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

|

North Dakota |

African-American / Black |

29.0% |

|

Oklahoma |

African-American / Black |

28.4% |

|

Nebraska |

Hispanic / Latino |

27.5% |

|

Nebraska |

African-American / Black |

27.4% |

|

Michigan |

African-American / Black |

27.4% |

Lowest Food Insecurity Prevalence by State and Race/Ethnicity

|

State |

Race/Ethnicity |

Food Insecurity Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

|

District of Columbia |

White |

1.3% |

|

Texas |

Asian / Pacific Islander |

4.4% |

|

Illinois |

Asian / Pacific Islander |

4.5% |

|

New Jersey |

White |

4.8% |

|

Maryland |

White |

5.4% |

Publication

Underlying Factors of Medicaid Inequities: Conversations with Experts on Racism and Medicaid

Medicaid serves as a vital public health safety net for over 79 million people, including many from historically excluded or marginalized communities. There is a great opportunity to improve Medicaid programs’ accountability for persistent health inequities by confronting the historical and structural racism perpetuated in the administration, policies, and practices that undergird the program.

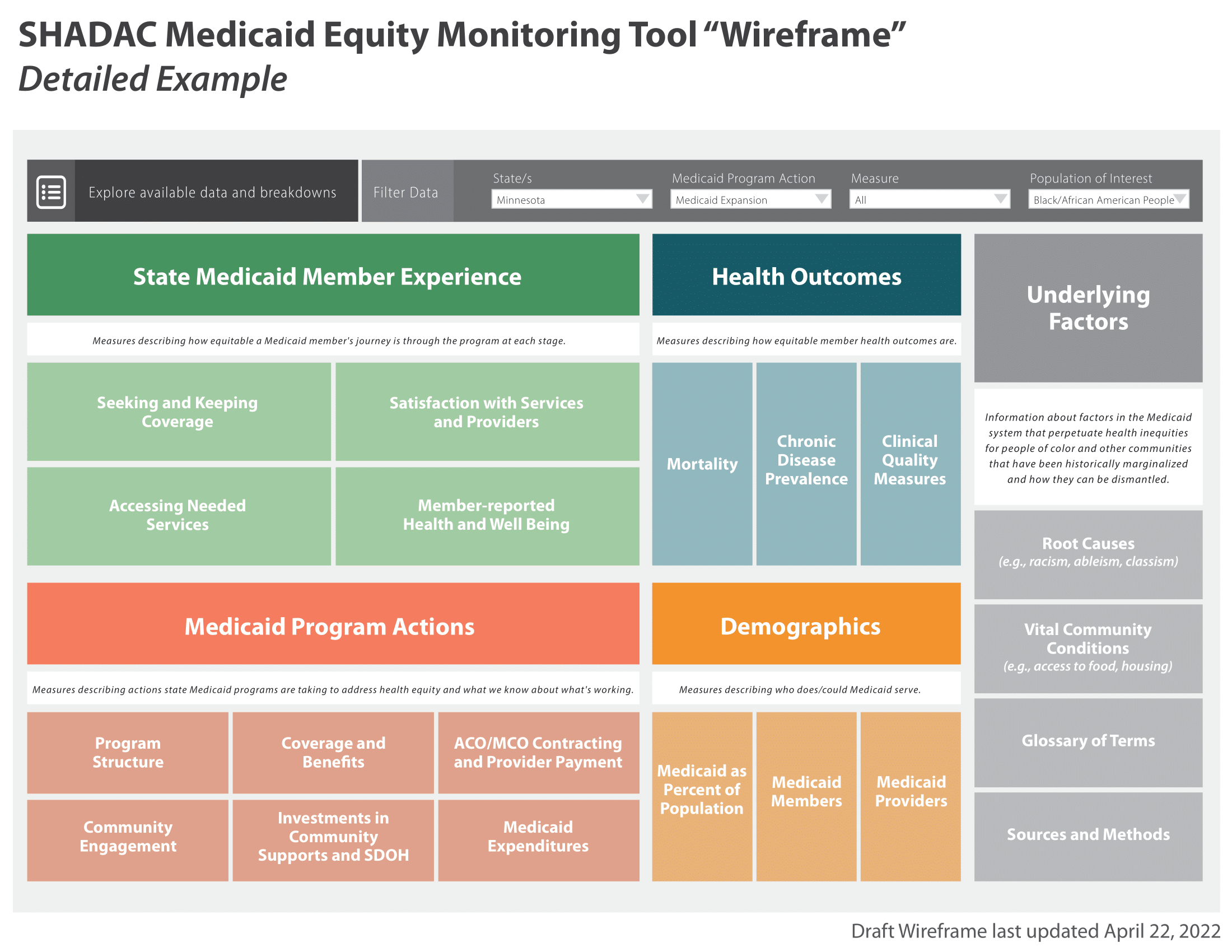

The Medicaid Equity Monitoring Tool (MET) project is a collaborative effort from the State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and partner organizations working to assess whether a data tool could increase accountability for state Medicaid programs to advance health equity while also improving population health.

During the first phase of this project, a wireframe was created to organize the different sections of a potential tool, including a section on "Underlying Factors" that lead to and perpetuate health inequities for people of color and other historically marginalized communities.

In order to inform the Medicaid Equity Monitoring Tool (MET) project and the Underlying Factors section of the tool, SHADAC produced an annotated bibliography of resources to better understand the available academic and gray literature on those underlying factors of health inequities in Medicaid.

While the bibliography covers a number of structural and systemic underlying factors of health inequities (e.g., ableism, sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination), most of the resources compiled in the bibliography address structural racism specifically. These resources discuss the history, policy context, and impacts of systemic racism on Medicaid recipients.

As a follow-up to the creation of the annotated bibliography, SHADAC’s Health Equity Fellow held consulting conversations with authors of select resources cited in the structural racism section. Through these conversations, our goal was to:

-

Connect with experts in order to elicit feedback on key insights from SHADAC’s annotated bibliography

-

Ask experts questions about what topics related to systemic racism need to be discussed within the tool

-

Discuss strategies on how best to convey and disseminate this important information

This brief summarizes these conversations, including specific examples and quotes from experts, for audiences interested in communicating about the effects of structural racism with the aim to dismantle it.

Publication

“American Indian 101”: Understanding the history and contemporary experiences of Native people in a United States health policy context

American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) is a racial/ethnic category that describes people with ancestry indigenous to North America prior to colonization in 1492. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, there were approximately 9.7 million Americans who identified as Native American alone or as Native American in combination with another race.

Despite millions of Americans identifying as AI/AN, Quin Mudry Nelson, MPH, SHADAC’s inaugural Health Equity Fellow, noticed a lack of attention on Indigenous and American Indian health and health care systems throughout their education. With their lens on health equity combined with their own experience as a Native person, they knew that Indigenous people in the U.S. face a number of health disparities compared to other groups, including, among others, the highest uninsured rate, lowest life expectancy at birth, and adverse impacts to health outcomes.

They also saw that it wasn’t only American Indian health services and systems being overlooked, it’s the people as well: data collection on AI/AN individuals is, and has been, a known challenge in the U.S. One report from the Department of Labor describes “substantial” criticism received “from tribes and other stakeholders regarding population undercounts, the accuracy and timeliness of the data, and the burden for tribes, due to lack of sufficient resources and trained personnel, in reporting the data to the Federal Government.”

After seeing these gaps between her education and her knowledge & experiences “as a two-spirit, Native person who is tribally affiliated with the Oneida Nation, I wanted to write a piece about AI/AN people’s history and identity in the context of health policy,” says Quin.

Quin’s in-depth research combined with their experience and understanding of the AI/AN community has culminated in this important brief: “American Indian 101”: Understanding the history and contemporary experiences of Native people in a United States health policy context.

Focused on health care and health insurance access among American Indian and Alaska Native people, this brief provides readers with essential context and commentary on United States and American Indian health policy, health disparities, and AI/AN identity as it relates to health care and policy.

The brief is divided into four sections, organized and grounded in the indigenous ways of knowing – outlining the present, reflecting upon the past, and using that context to chart a path for the future:

- Section 1 describes information about AI/AN people within the United States and the health care system presently, providing demographic data, a brief explanation on contemporary data collection issues, and a breakdown of the unique care delivery structure of the Indian Health Service

- Section 2 provides an overview of early U.S. history and American Indian health and social policies, including pivotal legal cases

- Section 3 contextualizes how this history constructed a unique identity for AI/AN people in comparison to other racial groups that impacts not only their access to care, but also to their “dedicated” health services

- Section 4 concludes with an overview of recent progress in AI/AN health and social policy, highlighting both potential future directions and limitations

This brief provides important historical context and actions that have shaped the landscape of American Indian health care today. Not only that, but this brief also provides a distinct perspective from an individual who has the lived experience of AI/AN people along with experience and education in public health and health equity.

Quin’s voice and ideas found in this brief are as intriguing as they are important. Publications with a foundation of personal perspective & experience such as this one are essential for uplifting voices from historically marginalized groups, identifying & spotlighting the structural issues that individuals face, and learning from the stakeholders who are impacted directly and indirectly.

Read the brief in full here or click on the image of the cover page above. We welcome any questions or comments – you can send them to Quin directly at nels9793@umn.edu.

Are you curious about American Indian health statistics, data collection, health care, health disparities, and more? You can start by delving into the references that informed this brief - these resources are rich with information. You can continue learning with some of the following SHADAC products and resources:

- Explore State Health Compare: Health Insurance Coverage by Race/Ethnicity (Includes AI/AN Breakdown)

- SHVS Brief: Collection of Race, Ethnicity, Language Data on Medicaid Applications: New and Updated Information on Medicaid Data Collection Practices in the States, Territories, and D.C.

- SHADAC Brief: The Kids Aren't Alright. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Implications for Health Equity

Blog & News

What is Health Equity? — A SHADAC Basics Blog

October 28, 2024:

Basics Blog Introduction

SHADAC has created a series of “Basics Blogs” to familiarize readers with common terms, concepts, and topics that are frequently covered.

This Basics Blog will focus on the concept of health equity. We will answer and provide explanations for questions like:

- What is health equity?

- What is the definition of health equity?

- How can we talk about health equity in public health work?

- What are other supplemental terms and their definitions that are used in the health equity space?

With that foundation set, we then move into an example, using a study on provider discrimination data drawn from the Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) to understand how to apply a health equity lens to public health work and analysis. Finally, we end with some further thoughts and considerations on our evolving understand of this complex concept.

Keep on reading below to learn more about health equity.

Health Equity Definitions

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to advancing health equity and dismantling barriers in health care, defines health equity below:

It is important to note, though, that since health equity is conceptual, there is not a singular definition of it. This definition can also change and evolve, so it’s important to continue to educate yourself on health equity as time goes on.

What Is the Difference Between Equity and Equality?

While these two concepts are similar, equity and equality are not one in the same.

Equality is defined as giving the same treatment to everyone, regardless of individual needs or differences.

Equity is defined as giving treatment that is specific to individual needs, which allows everyone a fair chance at being successful.

The graphic below from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation provides a visual representation of the difference between equality and equity. In the ‘Equality’ example, all people are given the same mode of transportation – they are given equal treatment. However, because the individual’s needs are not considered, the outcome is not necessarily equal as can be seen in the visual. In the ‘Equity’ example, each individual is given a mode of transportation that works for their needs, leading to a more equitable outcome as can be seen in the example.

Source: Joan Barlow, “We Used Your Insights to Update Our Graphic on Equity” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, November 2022, We Used Your Insights to Update Our Graphic on Equity (rwjf.org). Reproduced with permission of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, N.J.

Additional Terminology Definitions

The topic of health equity is complex, with many factors feeding into it. To further understand health equity, it is important to define these additional factors and terms as well. While this list is not exhaustive, the terms below all refer to larger barriers and systems that must be addressed in order to reach equity in health and health care.

Health Disparities: Avoidable differences in health outcomes experienced by people with one characteristic (race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.) as compared to the socially dominant group (e.g., white, male, cis-gender, heterosexual, etc.).

Measuring disparities can benchmark progress toward achieving health equity.

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH): The daily context in which people live, work, play, pray, and age that affect health. SDOH encompass multiple levels of experience from social risk factors (such as socioeconomic status, education, and employment) to structural and environmental factors (such as structural racism and poverty created by economic, political, and social policies).

These factors are known quantities that contribute to social and health inequities.

Social Inequities: Differences between groups that are unfair, unjust, systemic, and avoidable. Social inequities can be characterized by race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, income, etc.

Social inequities can lead to poor health outcomes and further perpetuate systems and circumstances leading to health disparities (systemic racism, ableism, etc.).

Structural Racism: A complex system rooted in historical and current realities of differential access to power and opportunity for different racial groups. This system is embedded within and across laws, structures, and institutions in a society or organization. This includes laws, inherited disadvantages (e.g., the intergenerational impact of trauma) and advantages (e.g., intergenerational transfers of wealth), and standards and norms rooted in racism.

Structural racism contributes to a number of social determinants of health (SDOH). Public health systems must prioritize addressing structural racism as a primary barrier to health equity.

As you can see, many of these terms contribute to each other or are a result of another—truly showing how complex the topic of health equity is.

Using a Health Equity Lens on Provider Discrimination—Challenges and Interventions

Now that we have gone over some helpful terminology to keep in mind, let’s look at how to apply a health equity lens when looking at a real-life public health example.

The example we will go over in this section is related to LGBTQ+ health equity and discrimination. With roughly 13.9 million adults in the United States identifying as LGBTQ+, this example is both relevant and important for conversations on equity. Individuals of minoritized sexual orientation and gender identity have been historically marginalized, underrepresented in data, and faced with many health disparities, compared to their heterosexual, cisgender counterparts. These disparities exist for LGBTQ+ people not only at the national level, but also at the community, organizational, and smaller societal levels.

Thus, in June 2022, President Biden signed Executive Order 14075: Advancing Equality for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Individuals. This executive order is a sign of progress toward breaking down systemic barriers and more relatedly for this blog, empowering the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “promote the adoption of promising policies and practices to support health equity” for this population.

Now we will look specifically at a relevant measure from the Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) – provider discrimination by sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) in Minnesota – to demonstrate how we can perform studies, analyze results, and identify accessible solutions to health disparities by viewing them through a health equity lens.

The Data

Data coming from the 2021-2023 Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) reveals that among all adults in Minnesota, over half of the transgender/non-binary population (56.3%) reported experiencing Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity (SOGI) based discrimination from health care providers – significantly higher compared with cisgender adults’ reported experiences of discrimination (6.7%).

Nearly 9 in 10 transgender/non-binary adults (88.1%) and about one in four (24.1%) cisgender adults who identified as gay/lesbian reported discrimination. Two thirds of transgender/non-binary adults (66.1%) and about a quarter of cisgender adults (23.9%) that chose the ‘none of these’ option for sexual orientation also reported discrimination. Discrimination among people who identify as bisexual/pansexual is also high, and not statistically different for transgender/non-binary adults (40.5%) and cisgender adults (31.6%).

Experiencing discrimination has been shown to negatively affect both mental and physical health, as individuals and members of historically marginalized communities report worse health status and may forgo or delay care to avoid further discrimination.

Now, let’s look at potential ways to equitably address instances of provider discrimination by sexual orientation and gender identity at various levels.

Community Level

There are various ways to approach the issue of addressing provider discrimination. One potential solution is to make changes to education for the overall medical community, such as implementing cultural competency and communication training.

Cultural competency describes services, practices, and processes that are responsive to diverse practices, assets, needs, beliefs, and languages for an array of individuals and communities. Examples of incorporating cultural competence in health care include:

- Promoting awareness and knowledge

- Recognizing one’s biases

- Engaging in cultural competence & bias training

- Using accessible language

- Familiarizing oneself with the local community

- Recruiting diverse team members

Embracing these strategies can help immensely in understanding and reducing stigma as well as strengthening relationships between providers and the unique communities they serve.

Incorporating cultural competence into care can therefore offer meaningful ways to make strides toward reducing reported discrimination rates, such as those from individuals reporting SOGI-based provider discrimination in Minnesota. When cultural competence is practiced, better and more equitable health outcomes are observed for patients. Improved trust and communication between providers and patients can lead to more regular interactions with the health care system (like routine preventative visits), which can in turn lead to better treatments, health outcomes, and even better overall health status, another known issue for LGBTQ+ individuals.

Organizational Level

Addressing provider discrimination at a higher organizational level can be done through changing health systems and how they operate. Structural issues, such as payment/reimbursement structures, lack of time for visits, and workforce diversity may also contribute to the discrimination felt by different individuals.

Structural competency, which is the belief that inequalities in health must be conceptualized in relation to the institutions and social conditions that determine health related resources, can then play a crucial role in promoting equitable care alongside cultural competency by addressing issues at a structural level. This concept can be implemented in health systems through training in five core competencies:

- Recognizing the structures that shape clinical interactions

- Developing an extra-clinical language of structure

- Rearticulating “cultural” formations in structural terms

- Observing and imagining structural interventions

- Developing structural humility

Structural training and education helps medical professionals more effectively understand the economic and social determinants of health (SDOH) that occur for their patients before any interaction with the health care system occurs. In the instance of individuals belonging to the LGBTQ+ community, these can take the shape of lack of health insurance coverage or access barriers. Additionally, organizations can invest in structural changes to advance health equity through improved data systems that are able to track populations’ diverse makeup (race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, primary language), alongside SDOH (income, education, employment) and health needs (utilization of care, treatment, and health outcomes), to better understand who they are serving and how to improve services.

Societal Level

On a larger scale, the state of Minnesota has made it a goal to ensure all Minnesotans receive high quality health care, free of provider or system bias.

Citing the 2021 Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA) data on responses to unfair treatment, the Minnesota Department of Health (DHS) recognized the disparity between the higher rates of unfair treatment by Black Minnesotans (39%) and Transgender Minnesotans (50%) compared to White Minnesotans and cis-gendered men (9% and 12%, respectively), and created a measurable goal to directly address this issue.

By 2027, MN DHS states that it hopes to reduce the percentage of transgender and non-binary Minnesotans and Black Minnesotans reporting unfair treatment by their providers by 50%. This goal is a meaningful step toward health equity for individuals with different racial and ethnic backgrounds and different gender identities.

Shifting Definitions and Future Considerations

In the example above, examining reported rates of provider discrimination in Minnesota and potential solutions at different levels helps to understand not only a practical example of how better understanding of health equity and systemic issues can clarify what the major barriers to advancing equity look like, but also how they can be addressed.

Even now as the definition of health equity is not set in stone and continues to evolve, we see opportunity for solutions to advance health equity--both in general, and for people with minoritized sexual and gender identities--to evolve as well. However, this does not apply only to health equity, as the definitions and understanding of many of the terms described above have evolved over time. As society and demographics continue to shift, so does our insight and understanding of these concepts.

There is a need for more involvement at the community, organizational, and societal level in advancing health equity. While there is progress in the right direction, there are still structural barriers that need to be overcome and met with applicable solutions that lead to positive systemic change.

Interested in learning more about health equity? Now that you have the SHADAC Basics down, try some of the following resources to continue to expand your knowledge:

Publication

Impact on Vital Community Conditions: Underlying Factors of Medicaid Inequities Annotated Bibliography

*Click here to jump to the 'Impact on Vital Community Conditions' annotated bibliography*

The State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and in collaboration with partner organizations is exploring whether a new national Medicaid Equity Monitoring Tool could increase accountability for state Medicaid programs to advance health equity while also improving population health.

During the first phase of this project, a conceptual wireframe for the potential tool was created. This wireframe includes five larger sections, organized by various smaller domains, which would house the many individual concepts, measures, and factors that can influence equitable experiences and outcomes within Medicaid (see full wireframe below).

While project leaders and the Advisory Committee appointed at the beginning of the project all agree that the Medicaid program is a critical safety net, they specifically identified the importance and the need for an “Underlying Factors” section of the tool. This section aims to compile academic research and grey literature sources that explain and provide analysis for the underlying factors and root causes that may contribute to inequities in Medicaid.

|

|

|

- Historical context of Medicaid inequities

- Information on how underlying factors perpetuate inequities in Medicaid

- Potential solutions for alleviating inequities within Medicaid

Once selected, researchers compiled sources in an organized annotated bibliography, providing a summary of each source and its general findings. This provides users with a curated and thorough list of resources they can use to understand the varied and interconnecting root causes of Medicaid inequities. Researchers plan to continually update this curated selection as new research and findings are identified and/or released.

Sections of the full annotated bibliography include:

- Systemic Racism

- Systemic / Structural Ableism

- Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Gender Affirming Care Discrimination

- Reproductive Oppression in Health Care

- Impact on Vital Community Conditions

This page is dedicated to a single section from the full annotated bibliography:

Impact on Vital Community Conditions

Underlying Factors Annotated Bibliography: Impact on Vital Community Conditions

Have a source you'd like to submit for inclusion in our annotated bibliography? Contact us here to propose a source for inclusion.

Click on the arrows to expand / collapse each source.

Semprini, J., Ali, A. K., & Benavidez, G. A. (2023). Medicaid Expansion Lowered Uninsurance Rates Among Nonelderly Adults In The Most Heavily Redlined Areas. Health Affairs, 42(10), 1439–1447. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00400

Author(s): Jason Semprini, University of Iowa, College of Public Health; Abinasir K. Ali, University of Iowa, College of Public Health; and Gabriel A. Benavidez, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of South Carolina

Article Type: Peer-reviewed journal

While there has been ample research on the effect of Medicaid expansion on reducing individual-level racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage, authors here attempt to fill the gap in research on how Medicaid expansion is affected by root causes of health inequities, such structural racism, as measured by the historically racist policy of residential redlining. The federal government’s rating system for mortgage investments, which benefited white, upper middle-class families and penalized minoritized communities and the working-class, has had lasting effects even after it was outlawed in the late 1960s. These effects include substantial wealth gaps, under-resourced communities, and poorer health outcomes. The authors use data from national surveys and a difference-in-differences design to explore how exposure to historical redlining may have influenced the effect of Medicaid expansion on population-level insurance rates for non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and Hispanic nonelderly adults. When comparing uninsurance rates in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states before and after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, authors found that Medicaid expansion had the greatest impact on lowering uninsurance rates in areas with the highest level of historic redlining. Even though no statistically significant differences were observed by race and ethnicity within each redline category, authors conclude that “Medicaid expansion may have helped to reduce some of the negative consequences of structural racism…” and emphasize the importance of studying contextual factors when evaluating health programs and policies.

Londhe, S., Ritter, G., & Schlesinger, M. (2019). Medicaid Expansion in Social Context: Examining Relationships Between Medicaid Enrollment and County-Level Food Insecurity. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 30(2), 532–546. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2019.0033

Author(s): Shilpa Londhe, Department of Health Policy and Management, Yale School of Public Health; Grant Ritter, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, Mark Schlesinger, Department of Health Policy and Management, Yale School of Public Health

Article Type: Peer-reviewed journal

This article studies the relationship between county Medicaid enrollment and food insecurity in over 350 counties. The authors acknowledge that food insecurity prevalence ranges widely across the country, from as low as 4 percent up to 39 percent in some states. The authors observe that counties who expanded their Medicaid program in 2012 had significantly reduced food insecurity compared to their baseline year of 2009, and compared to counties that expanded later in calendar year 2014. While the authors acknowledge that food insecurity and lack of insurance coverage are likely related, they conclude that Medicaid likely offers greater financial security overall, which alludes to many improvements for low-income families, with overcoming food insecurity being one positive of many likely effects.

Bowen, S., Elliott, S., & Hardison-Moody, A. (2021). The structural roots of food insecurity: How racism is a fundamental cause of food insecurity. Sociology Compass, 15(7). https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12846

Author(s): Sarah Bowen, Professor of Sociology at North Carolina State University; Sinikka Elliot, Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia; Annie Hardison-Moody, Associate Professor of Agricultural and Human Sciences at North Carolina State University

Article Type: Peer-reviewed journal

This article, written by scholars in the US and Canada and funded by the US Department of Agriculture, provides a detailed overview of the patterns of food insecurity in the recent past. These patterns of food insecurity include that it is associated with lower income households, mostly cyclical as opposed to chronic, more prevalent in households with children and in households headed by women, and households headed by people of color and people with disabilities. Food insecurity also has negative effects on physical and mental health as well as academic performance and risk of hospitalization among children. Authors summarize evidence on the association between food insecurity and poverty, other forms of hardship, housing insecurity, and neighborhood support systems, but argue that there is a more fundamental cause for food insecurity: racism and persistent unequal access for people of color to opportunities and resources. To combat food insecurity, structural change is needed. While the article does not go into detail about specific recommendations for the Medicaid program, it references advocating for Medicaid expansion and against “...punitive and stringent policies that disproportionately harm people of color…,” which can be the price for access to assistance.

Charania, S. (2021). How Medicaid and States Could Better Meet Health Needs of Persons Experiencing Homelessness. AMA Journal of Ethics, 23(11), E875-880. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2021.875

Author(s): Sana Charania, George Washington University’s School of Public Health in Washington, DC

Article Type: Peer-reviewed policy reform brief

This peer-reviewed policy reform brief includes a list of strategies that state Medicaid programs can pursue with providers to alleviate health care stressors of those experiencing homelessness. The author remarks that in 2020, over half a million people experience homelessness on any given night in the United States. According to survey data from a decade earlier, about a quarter of “…sheltered persons experiencing homelessness had a severe mental illness and 35 percent had problems with substance use”. The author states that there is a need for better supportive housing options and discusses studies in several states that showed providing permanent housing and needed services (such as behavioral health care) to individuals who were previously homeless led to decreased inpatient or emergency department visits and lower health care costs. The author emphasizes that it is not entirely on state Medicaid programs to reach those experiencing homelessness; clinicians and hospitals have a role to play in resolving biases about this very stigmatized group of people and assessing the basic needs of their patients. The author does highlight the importance of Medicaid expansion under the ACA – citing the improved health conditions of those experiencing homelessness and an increase in coverage in expansion states.

Dennett, J. M., & Baicker, K. (2022). Medicaid, Health, and the Moderating Role of Neighborhood Characteristics. Journal of Urban Health, 99(1), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-005792

Author(s): Julia M. Dennett, Yale University School of Public Health, New Haven, CT; Katherine Baicker, University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy, Chicago, IL and the National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Article Type: Peer-reviewed journal

This article is an analysis of whether key neighborhood characteristics, such as “socioeconomic deprivation (which is a score that reflects neighborhood ethnicity, education, employment, poverty, and housing/crowding), food access, park access and green space, attributes that promote active living, and land use” influence the effect of health insurance coverage on health outcomes. Using data collected in 2009 and 2010 about participants in the Oregon Health Insurance living in the Portland area, some of whom had access to Medicaid coverage and some of whom did not, authors found neighborhood characteristics played only a limited role in moderating the impacts of coverage on select health outcomes. The study’s null findings imply that Medicaid expansion benefited many across the board, regardless of neighborhood. Also implied is that the relationship between coverage and neighborhood characteristics and health outcomes is complex. Authors note several study limitations, including other factors to consider in the definition of neighborhood characteristics and their inability to conduct subgroup analyses. They also call for future research to inform policy.

Satcher, L. A. (2022). (Un) Just Deserts: Examining Resource Deserts and the Continued Significance of Racism on Health in the Urban South. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 8(4), 483–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/23326492221112424

Author(s): Lacee Satcher, Professor of Sociology and Environmental Studies at Boston College

Article Type: Peer-reviewed journal

This peer-reviewed article summarizes research examining the relationship between resource scarcity (measured in terms of multiply-deserted areas (MDAs)) and health. The author goes on to discuss how this relationship varies according to race and class composition of urban neighborhoods in the South and its implications for public programs, including Medicaid. MDAs were constructed based on three types of resource deserts: food, green spaces, and pharmacy deserts. Health outcomes examined included adults with diabetes, obesity, asthma, and no leisure-time physical activity. Results show that, compared to less resource-scarce areas, MDAs are associated with higher disease prevalence as well as higher rates of inactivity. Co-occurring resource scarcity has more influence on outcomes and activity levels than single-resource scarcity resulting in greater stress and negative impacts on health. “While there have been efforts to increase food access or greenspace for low-income, predominantly Black neighborhoods via farmer’s markets and community gardens, understanding that these neighborhoods are experiencing compounded, co-occurring resource scarcity calls for a more comprehensive policy intervention or community initiative that increases access to healthy foods, greenspace, and prescription medicines.” The author explains further that, “reducing disparities in prescription access and adherence via expansion of Medicare Part D and Medicaid are important, but study findings suggest that policy efforts to reduce disparities should also increase spatial access to pharmacies.”

Wei, Y., Qiu, X., Sabath, M. B., Yazdi, M. D., Yin, K., Li, L., Peralta, A. A., Wang, C., Koutrakis, P., Zanobetti, A., Dominici, F., & Schwartz, J. D. (2022). Air Pollutants and Asthma Hospitalization in the Medicaid Population. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 205(9). https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202107-1596oc

Author(s): Yaguang Wei, Xinye Qiu, Mahdieh Danesh Yazdi, Longxiang Li, Adjani A. Peralta, Cuicui Wang, Petros Koutrakis, Antonella Zanobetti, are all from the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Matthew Benjamin Sabath Francesca Dominici are from the Department of Biostatistics at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Kanhua Yin is from the Department of Epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; and Joel D. Schwartz is associated with both the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health as well as the Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School.

Article Type: Peer-reviewed journal

This peer reviewed study analyzes inpatient claims of Medicaid beneficiaries from 2000 to 2012 by zip code in order to determine the effect of three common air pollutants (nitrogen dioxide, ozone pollution, and particulate matter) on asthma hospitalizations. The researchers found a positive relationship between short-term exposures and increased risk of asthma hospitalization for those with one asthma admission during the study period, but air pollutants appeared to be less of a factor for those with multiple asthma admissions during the study period. A community-level analysis found higher risk of asthma hospitalization for people living in low population density zip codes, people with higher average BMI, and people living a longer distance to the nearest hospital. There were no significant differences in risk of asthma hospitalizations by race or ethnicity. These results emphasize the importance of both individual and contextual factors in assessing the quality of health care for the Medicaid population, where the impact of air pollutant exposures on asthma susceptibility differed by severity and place characteristics.

[1] State Health & Value Strategies (SHVS). (2021). Talking about anti-racism and health equity: Discussing racism. https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Talking-About-Anti-Racism-Health-Equity-1-of-3.pdf