“Forgone care” describes when someone does not use or access health care despite a need for it. While there are a number of reasons why someone might choose to forgo care (e.g., fear of medical procedures or diagnosis, lack of health literacy and/or understanding, limited access to care, cultural beliefs), a very common reason for many is the cost of health care.

Whatever the reason, forgoing or delaying care is correlated with poorer health outcomes, delayed diagnoses, and disruption in care for chronic conditions.1,2 And, unfortunately, disrupted and/or forgone care can actually increase costs for some through further complications, missed preventative treatments, and later diagnoses.

Health care costs are rising in the United States3, and the prices of many other essentials have also gone up since the pandemic.4 As costs and overall pressures on family budgets continue to rise5, it is possible that people will also be more likely to forgo health care.

SHADAC’s State Health Compare tool tracks the percentage of adults who report forgoing care due to cost using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). In 2023, it’s estimated that 11.6% of adults could not get medical care when they needed it due to cost.

While 11.6% represents how many of all adults reported forgoing care due to cost in 2023, we can look deeper at the phenomenon of forgone care by disaggregating the data and looking at how different factors, like insurance coverage type, sexual orientation, and race / ethnicity, impact rates of forgone care.

Looking at how forgone care due to cost appears for different groups and communities can help us identify disparities that may not be clear from the aggregated data, understand how structural and/or systemic racism might impact health care decisions and outcomes, and help policymakers and others target efforts to make care more accessible.

In this blog post, we are going to explore racial disparities in forgone health care due to cost. Using SHADAC’s State Health Compare tool, we will examine forgone care data broken down by race and ethnicity. Then, we will explore racial disparities in forgone care at the state level.

National Levels of Forgone Care Higher Among Hispanic/Latino, Black, and Other/Multiple Race Adults Compared to White Adults

Using State Health Compare, we examined national levels of forgone care over time for all available race/ethnicity breakdowns: Hispanic/Latino, Black, White, and Other/Multiple Races between 2011 and 2023.

Figure 1. Percent of Adults Who Could Not Get Medical Care When Needed Due to Cost by Race/Ethnicity

Figure 1 shows that each racial / ethnic group’s forgone care follows a similar trendline. Despite similar trends, White adults consistently report the lowest rates of forgone care due to cost. While rates of forgone care due to cost have decreased for all groups compared to 2011, the racial disparities are clear and persistent.

In 2023, rates of foregone care for Black adults (12.7%) and Hispanic/Latino adults (20.1%) were statistically significantly higher than the overall rate (11.6%) and the rate for Whites (8.6%). Since 2021, the percentage of Hispanic / Latino adults who forgo care due to cost has been at least 10 percentage points (PP) higher than White adults.

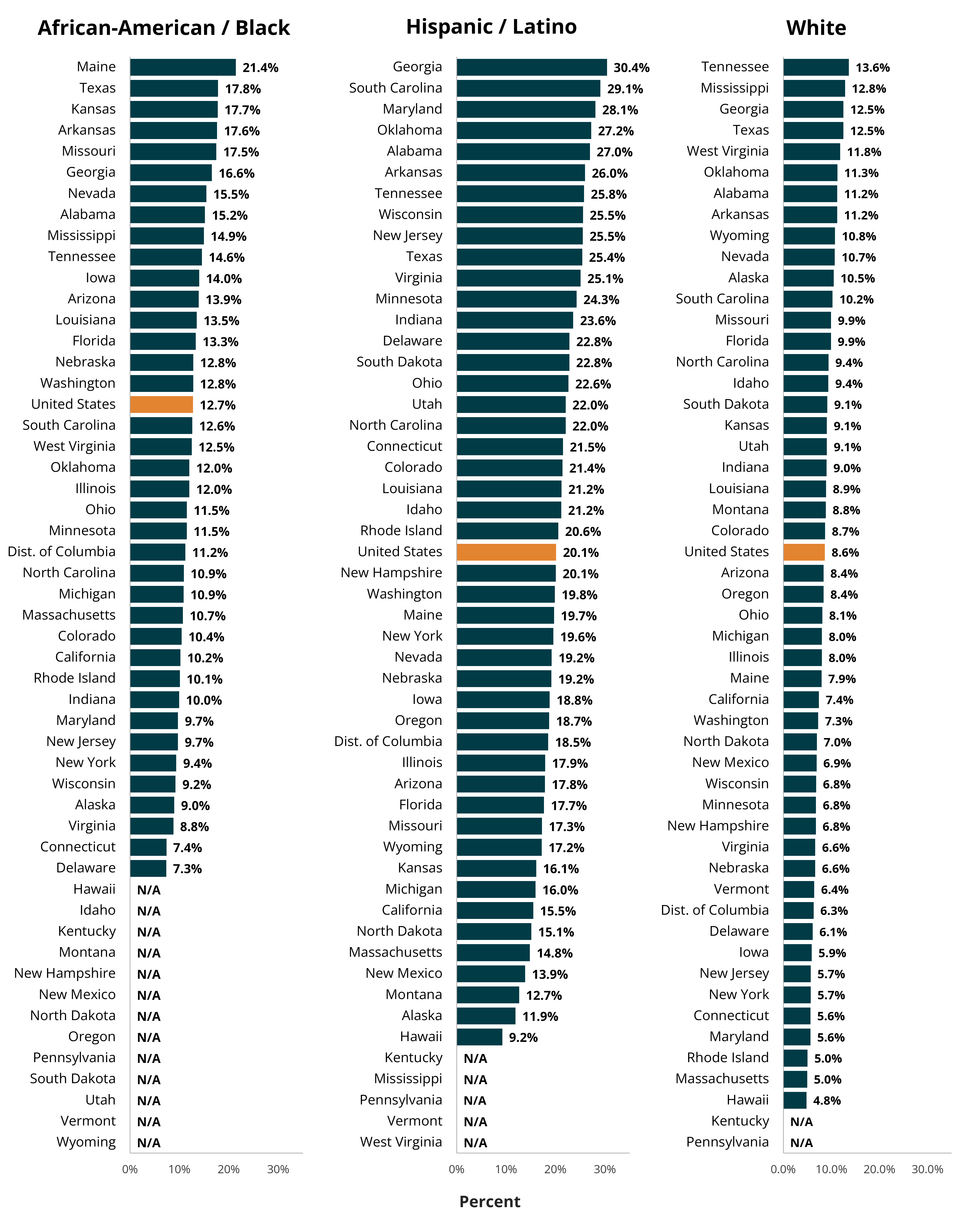

Forgone Care Due to Cost Differs by State, Ranges Widen for Hispanic/Latino and Black Adults

There is considerable variation across states in the rates of forgone care by race and ethnicity. As Figure 2 shows, state by state rates of forgone care due to cost range from 4.8% of White adults in Hawaii to 30.4% of Hispanic/Latino adults in Georgia .

Figure 2 also highlights the extent to which the range of forgone care across states differs by race and ethnicity, with Hispanic/Latino adults having higher rates consistently across states. For example, the highest rate among Hispanic/Latino adults (Georgia, 30.4%), is more than double the highest rate for White adults (Tennessee, 13.6%). Similarly, the lowest rate among Hispanic/Latinos (Hawaii, 9.2%) is close to double the lowest rate for White adults (Hawaii, 4.8%).

Figure 2. Forgone Care Due to Cost for Black, Hispanic, and White Adults by State

Low Rates of Forgone Care Overall Mask Racial Disparities

Figure 3 ranks the fifty states and D.C. by overall rates of forgone care. As shown, Hawaii, Vermont, Massachusetts, Iowa, and New Hampshire have some of the lowest rates of foregone care in the country.

Figure 3. Forgone Care Due to Cost for All Adults by State

What happens when we breakdown by race / ethnicity?

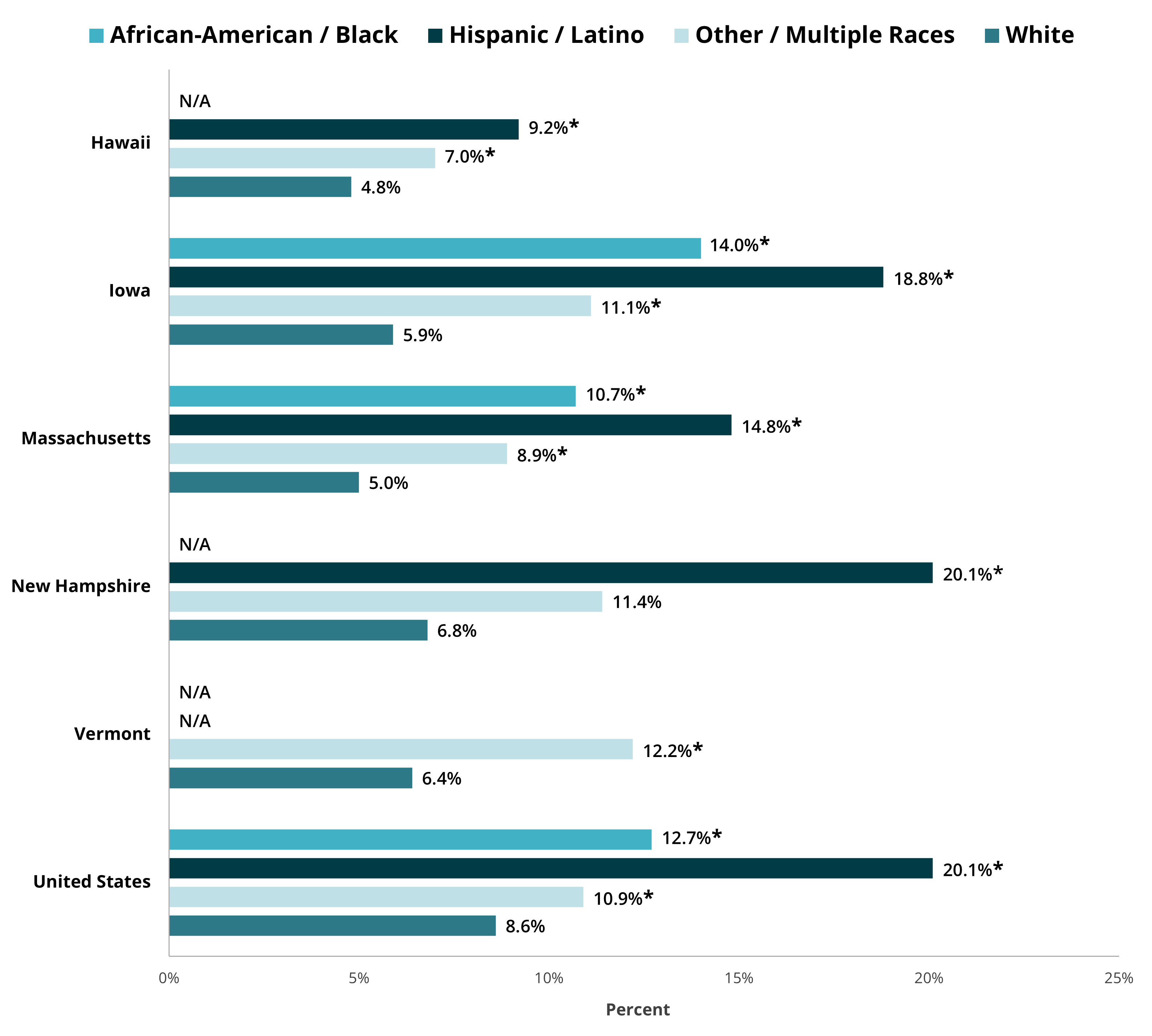

Figure 4. Forgone Care Due to Cost By State and By Race / Ethnicity

*Significant difference from White

When we disaggregate the data in states with low overall rates of forgone care, racial disparities are revealed.

Let’s take Massachusetts as an example since that is a state where we have data for each group. In Massachusetts, the only group that has a rate equal to or less than the overall rate is White adults at 5.0%. All of the other racial / ethnic groups with available data have rates that are significantly higher than White adults, with Black adults having more than double (10.7%) and Hispanic/Latino adults having almost triple (14.8%) the rate of forgone care compared to White adults.

Health Equity Considerations & Conclusion

Racial disparities in health care can come in a number of forms; as seen in this blog, there are important disparities in forgone care among adults by race and ethnicity. These disparities appear in most states, even states with low overall rates of forgone care, and the disparities are even more stark in certain states. Low overall rates of forgone care can mask these racial disparities – disaggregating data and looking at differences between groups is crucial for identifying and closing gaps & health disparities.

In some circumstances in this blog , we used White as the comparison group to test for statistically significant differences across racial and ethnic groups. This was because White adults had the lowest rates of forgone care, and are, generally, the most structurally advantaged compared to the other groups.

However, we want to acknowledge that this method is not always appropriate; as Whitfield et al remarks in a study on comparing racial groups: “There is an assumption of differences, but different from what?” Continuously using White groups as the basis of comparison can perpetuate the false narrative that White is a “standard” that racial/ethnic minorities differ from, which serves to ‘other’ those minority groups instead of treating each as distinct, and varied, groups with different social, cultural, and systemic/structural influences.6

There are also equity issues related to data availability — states are much more likely to have insufficient data for Black, Hispanic/Latino, and people who identify as other/multiple races. Excluding PA and KY (both states did not have sufficient data to be included in the 2023 BRFSS public data file and are not included in the national data), data is not available for:

- Other/Multiple Race adults in two states (NC and RI)

- Hispanic/Latino adults in three states (MS, WV, and VT)

- Black adults in 11 states (HI, ID, MT, ND, NH, NM, OR, SD, WY, UT, and VT)

Improving data collection for those of minority groups on surveys like the BRFSS could help to highlight important differences between states and groups that are not visible with the current data.

Finally, we acknowledge that grouping responses in to “Other/Multiple Races” may obscure important disparities within this diverse group. Efforts are being made to improve demographic data collection, like the newly revised standards from the OMB on federal race/ethnicity data collection; improving sample size and data collection methodology are important steps towards centering health equity, making critical disparities visible to researchers, policymakers, and community members.

Continue to explore this and more data on our interactive online data tool, State Health Compare.

Notes

All statistically significant differences were based on two-sided t-tests at the 95% level of confidence, indicating that these changes were likely to reflect true changes in the population given the available data. Lack of statistically significant changes does not indicate certainty that there was no true population change, but rather that any true population change was not detectable with the available data.

These results represent rates of adults that forgo needed medical care due to cost for the civilian non-institutionalized population who are 18 years and over.

Citations

1. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2775366

2. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8683898/

5. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2024/renter-households-cost-burdened-race.html