Blog & News

SHADAC and CRC Brief Provides Pre-Legalization Data on Minnesota’s Cannabis Landscape

January 30, 2024:- Prevalence of cannabis use (in both adults and youth)

- Rates of symptoms of cannabis abuse and dependence, also commonly called cannabis use disorder or addiction

- Self-reported incidence of driving under the influence of cannabis

Ultimately, the data returned findings that may be useful in better understanding Minnesota’s cannabis landscape prior to legalization and offer a starting point for understanding where we may be headed.

Blog & News

Minnesota’s COVID-19 vaccine campaign left vulnerable groups with lagging rates

August 2, 2023:Health inequities are nothing new in Minnesota, but the pandemic placed them in a new light. Numerous studies have reported disparities in how COVID-19 affects many vulnerable groups, often placing them at higher risk of infection, hospitalization, and death. And the inequitable effects of the disease itself are not the only cause for alarm. Once COVID-19 vaccines received authorization, disparities in vaccination rates also became a concern, especially as surveys indicated widespread hesitancy and lagging uptake.

Partnering with the Minnesota Electronic Health Record Consortium, SHADAC delved deep into an analysis of COVID-19 vaccination rates in Minnesota. Unlike many other studies, we were able to examine not only how COVID-19 vaccination rates differed across different demographic groups, but also how those disparities developed over time. This type of analysis was possible because of the Consortium’s unique dataset, which matches data from large health care providers’ electronic health records—including detailed demographics with immunization records from the Minnesota Department of Health, ultimately covering almost all people who received a COVID-19 vaccine in the state.

Understanding the dynamics of vaccination disparities over time was a crucial element of our study. While we present data on COVID-19 vaccination rates for different demographic subpopulations at the end of 2022, we also examined the time it took to reach 50 percent of people in different demographic groups with COVID-19 vaccinations. That measure of time to vaccination is important because, in a public health crisis during which hundreds or even thousands of people were dying each day at its peak in the U.S. alone, the speed with which people were vaccinated was critical to saving lives.

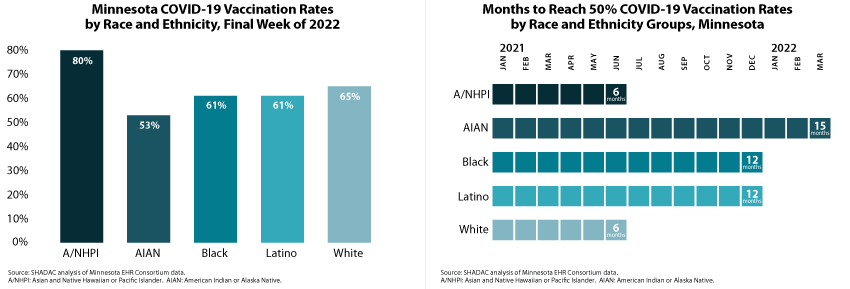

Our approach also allowed us to glean unique insights on COVID-19 vaccination disparities that are hidden below the headline numbers. For instance, although Minnesota’s Black, Latino, and White populations each had similar COVID-19 vaccination rates (61 percent, 61 percent, and 65 percent, respectively) at the end of 2022, they took distinctly different paths to reach that point. Within six months of the first COVID-19 vaccine receiving emergency use authorization, Minnesota vaccinated half of the state’s White population, but it took twice as long (12 months) for the state to vaccinate half of its Black and Latino populations.

Another crucial but under-recognized factor in COVID-19 vaccination disparities is the way public health policies placed some groups as a disadvantage in accessing vaccines in the early days of limited supply. Because experience showed that elderly people were at higher risk of severe disease and death from COVID-19, they were prioritized to be among the first people eligible for vaccines. But nationwide and in Minnesota, the White population skews older, effectively baking racial and ethnic disparities into the vaccine prioritization criteria. For that reason, we also stratified racial and ethnic groups’ COVID vaccination data by age—an approach that uncovered complex dynamics.

Another crucial but under-recognized factor in COVID-19 vaccination disparities is the way public health policies placed some groups as a disadvantage in accessing vaccines in the early days of limited supply. Because experience showed that elderly people were at higher risk of severe disease and death from COVID-19, they were prioritized to be among the first people eligible for vaccines. But nationwide and in Minnesota, the White population skews older, effectively baking racial and ethnic disparities into the vaccine prioritization criteria. For that reason, we also stratified racial and ethnic groups’ COVID vaccination data by age—an approach that uncovered complex dynamics.

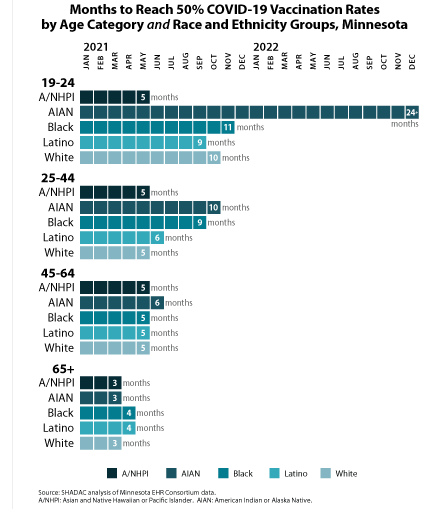

We found that disparities in COVID-19 vaccination rates were relatively small among Minnesota’s elderly population. For instance, Minnesota succeeded in vaccinating half of the elderly population across all racial and ethnic groups within three or four months—an example of how health inequities can be minimized. But disparities were stark among young adults, age 19-24. While Minnesota vaccinated half of Asian and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander young adults within five months, it took roughly twice as long to vaccinate half of Latino young adults (nine months), White young adults (ten months), and Black young adults (eleven months). And stunningly, Minnesota had failed to reach half of American Indian and Alaska Native young adults by the end of 2022—approximately 24 months after vaccines were first authorized.

We also examined COVID-19 vaccination rates by other demographic categories, finding higher vaccination rates and quicker vaccination progress among older population groups, urban and suburban communities, and females. Additionally, our study found disappointing rates of COVID-19 vaccination among children, particularly younger children. At the end of 2022, less than one-half of children age 5-11 had been vaccinated, despite having been eligible for vaccines for over a year; and less than one-tenth of children age six months to four years had been vaccinated, despite having been eligible for roughly six months. Despite a common, incorrect notion that COVID-19 is harmless for children, other researchers have found that COVID-19 was a top 10 cause of death for children during the pandemic, so those low vaccination rates are needlessly leaving Minnesota kids at risk.

Together, the findings from this new study highlight two main points: First, Minnesota’s COVID-19 vaccination efforts resulted in clear disparities. When looking at high-level data, it is easy to miss those disparities because some of them narrowed over time. But looking at detailed data illustrates the ways that certain groups were left vulnerable to COVID-19 for much longer than others. Second, our findings on disparities in the time Minnesota took to vaccinate half of different subpopulations demonstrate the importance of monitoring such health equity measures over time. Time is critical in an emergency such as the pandemic, and eventually closing gaps in health disparities simply isn’t good enough. Health equity requires urgency.

Publication

Disparities in Minnesota’s COVID-19 Vaccination Rates

A new SHADAC issue brief found stark disparities not only in the share of subpopulations that have been immunized against COVID-19 in Minnesota, but also in the length of time it took vaccines to reach most people in these different groups.

For instance, by the end of 2022, 80 percent of Asian and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander people in Minnesota were vaccinated against COVID-19, but only 53 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native people in the state were vaccinated.

|

Similarly, while Minnesota successfully vaccinated half of the state’s Asian and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander population and White population within six months of the first COVID-19 vaccine authorization, the state took fifteen months to reach vaccination for half of the American Indian and Alaska Native population. |

The study also found wider and more obvious disparities among younger segments of Minnesota’s population. For instance, half of the elderly population (age 65+) in all racial and ethnic groups were vaccinated within similar time frames of just three or four months. However, among young adults age 19-24, Minnesota was able to vaccinate half of Asian and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander young adults within five months but took roughly twice as long to reach half of Latino young adults (nine months), White young adults (ten months), and Black young adults (eleven months). And, shockingly, Minnesota had failed to reach half of American Indian and Alaska Native young adults by the end of 2022—almost two years after vaccines were first authorized.

The analysis also looked at vaccination data by categories of geography and sex, and for children separately, as vaccines for their age group were developed and authorized later than for adults. All data used in SHADAC’s analysis were provided through a collaboration with the Minnesota Electronic Health Record Consortium, a partnership of state health systems and public health agencies aimed at providing comprehensive and timely data to better inform policy.

Click on the image above to read the full brief.

Blog & News

Staying Alive in America: Minnesota Public Radio Feature

June 26, 2023:SHADAC Senior Research Fellow Colin Planalp recently joined Angela Davis on Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) News to discuss life expectancy in the United States. The segment centered on findings from multiple reports, including one out of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which showed that the United States’ average life expectancy is not just stagnating but actually decreasing, and a related National Academy of Medicine report comparing U.S. health and life expectancy to that of people in other wealthy countries.

Other health experts joined Planalp and Davis as they used data to scrutinize the severity of the issue and explain causes for the downward spike. The group noted that the issue is complex and doesn’t simply translate to older Americans losing a few years at the end of a long life. As Planalp put it, “If Americans make it to 65, their life expectancy doesn't look that bad; their life expectancy once they're elderly looks pretty good compared to different countries.” However, he continued, “the problem is that Americans are dying young.”

"...the problem is that Americans are dying young.”

- Colin Planalp

The panel cited gun violence as a contributor to many Americans dying younger than their counterparts in similarly wealthy countries. Planalp also attributed the inordinate increases in suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol related deaths–also known as deaths of despair–as an influencing factor on life expectancy. The reality that these public health crises are fatally impacting young adults was a throughline across each panelists’ remarks. And in order to save lives and reverse this trend, there is an urgent need for preventive efforts to help people avoid unnecessary illness and injury, as well as broader access to treatment for mental illness and substance use disorder.

Listen to the full segment here, and browse these related SHADAC resources:

Blog & News

Pandemic drinking may exacerbate upward-trending alcohol deaths

June 14, 2021:Even before 2020, alcohol-involved deaths reached a modern record

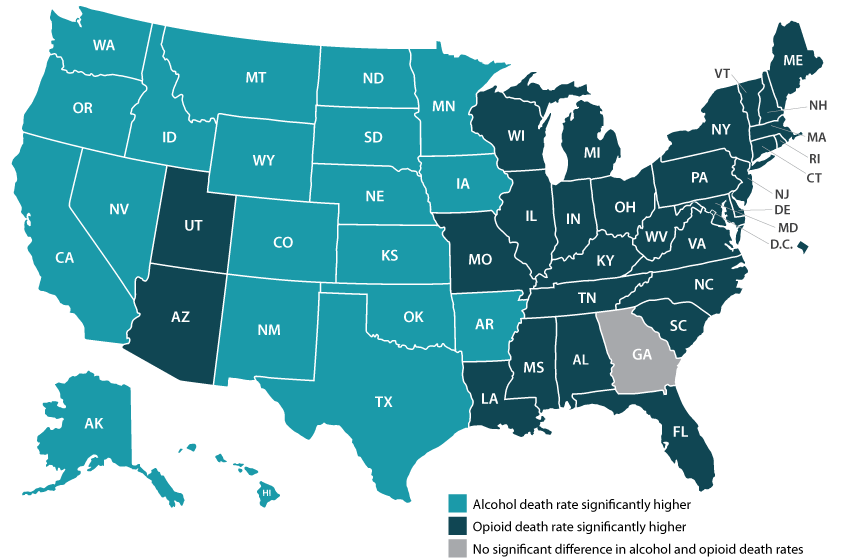

Considering the well-deserved attention paid to the opioid crisis in recent years, few people might guess that rates of alcohol-involved deaths were as high as or higher than opioid overdose death rates in nearly half of states (Figure 1).1 Like the opioid crisis, the trend in alcohol-involved deaths is also worsening, having grown by roughly 50 percent in just over a decade. All this was before the coronavirus crisis had even begun.

Figure 1. State alcohol death rates vs. opioid death rates, 2019

|

Data and analysis on alcohol-involved deaths Read more about growing alcohol-involved death |

Now, evidence is accumulating that the pandemic precipitated dangerous changes in the way people consume alcohol in the United States. For instance, research has found increased alcohol sales since the crisis began, a finding illustrated by data showing that liquor taxes represented a rare instance of increased revenues for some states, such as Minnesota, during the COVID pandemic.2,3 Other studies have found that U.S. adults report consuming more alcohol in order to deal with pandemic-related stress, and that they are drinking more frequently and engaging in more high-risk drinking behaviors, such as heavy drinking and binge drinking.4,5,6

As we climb our way out of the immediate crisis, the U.S. will need to shift attention back to long-running public health threats. Beyond the obvious toll of the virus itself, another legacy of the pandemic may be the exacerbation of existing problems, including alcohol-related deaths and the opioid crisis. The opioid crisis was commonly recognized before 2020, but the upward trend in alcohol deaths was still occurring largely under the radar (Figure 2). But recent attention to risky pandemic-related alcohol consumption can sharpen our focus on this emerging concern.

Figure 2. U.S. alcohol-involved death rates, 2000-2019

With alcohol especially, the U.S. has a window of opportunity to intervene before many people’s pandemic-era risky drinking habits result in deaths, since the bulk of alcohol-involved deaths result from years of excessive drinking. In the coming years, it will be vital for states to monitor and study these issues and to consider doubling down on policy initiatives to curb the tide through efforts such as enhancing access to treatment of substance use disorder and by persuading and assisting people in recalibrating their alcohol consumption to healthier levels.

Visit State Health Compare to explore state-level data on alcohol death and opioid death rates.

1 SHADAC Staff. U.S. alcohol-related deaths grew nearly 50% in two decades: SHADAC briefs examine the number among subgroups and states. https://www.shadac.org/news/us-alcohol-related-deaths-grew-nearly-50-two-decades. Published April 19, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2021.

2 Rebalancing the ‘COVID-19 effect’ on alcohol sales. Nielseniq.com. https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/2020/rebalancing-the-covid-19-effect-on-alcohol-sales/. Published May 7, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2021.

3 Ewoldt J. Liquor stores neared sales records for 2020 as bars, restaurants closed. Startribune.com. https://www.startribune.com/liquor-stores-neared-sales-records-for-2020-as-bars-restaurants-closed/573469221/. Published December 26, 2020. Accessed May, 12, 2021.

4 American Psychological Association. Stress in America: One year later, a new wave of pandemic health concerns. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2021/sia-pandemic-report.pdf. Published March 2021. Accessed May 12, 2021.

5 Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(9): e2022942. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942.

6 Grossman ER, Benjamin-Neelon SE, Sonnenschein S. Alcohol Consumption during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey of US Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(24): 9189. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249189