Publication

Presentation: Post-Reform Changes in Health Care Access and Affordability in Minnesota

Presentation by Giovann Alarcon at the 2016 Minnesota Health Services Research Conference, March 1, 2016, in St. Paul, MN.

Publication

Minnesota’s Accountable Communities for Health: Lessons from the First Year

Presentation by Donna Spencer at the 2016 Minnesota Health Services Research Conference, March 1, 2016, in St. Paul, MN.

Blog & News

Minnesota should keep our State-Based Marketplace. Here's why.

January 28, 2016:Earlier this month, the Minnesota Health Care Financing Task Force, of which I am a member, recommended that Minnesota continue operating MNsure as a State-Based Marketplace (SBM) rather than switch to a Federally-Facilitated Marketplace (FFM). I agreed with the recommendation. Here's why:

- Minnesota knows how to run successful healthcare programs for our residents, and we do it well.

The federal government issued new guidelines stating that an FFM will not accommodate state-specific programs or eligibility criteria. Moving to an FFM would therefore require that we dismantle MinnesotaCare, a program that is unique to Minnesota and offers generous benefits at a reduced premium to folks whose income is too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low for Marketplace coverage to be affordable, even with financial assistance. We would have to move the 76,000 individuals enrolled in MinnesotaCare to HealthCare.gov, where they would have to pay more for less generous coverage—ultimately making coverage less accessible for them. Minnesota has a long history and expertise in administering health insurance coverage programs, and we should continue to support our state-based initiatives. -

With an SBM, we keep premium assessments in Minnesota and control their growth.

The new FFM guidelines also require states to pay a fee for using the HealthCare.gov platform. This fee would go directly to the federal government, and the fee could increase over time at federal discretion. Currently, the premium assessment levied through MNsure stays in Minnesota to support Minnesota-specific programs, and we control any changes in the percentage of premiums assessed. -

An SBM promotes integration of eligibility and enrollment systems at both the state and county levels, and this integration helps Minnesotans efficiently enroll in coverage and maintain benefits.

Minnesota has been working on an integrated eligibility and enrollment system that links MNsure, MinnesotaCare, and Medicaid while also providing a platform for the integration of other public programs (e.g., the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP) to help the state and counties more efficiently administer Minnesota programs and services across the board. This level of integration will boost operational efficiency, help the nearly 900,000 individuals enrolled in Minnesota’s healthcare programs maintain their coverage consistently, and ensure that folks are benefitting from all the programs and services for which they are eligible.

Integration progress has been slow, but it is happening, and integration is worth working on and supporting. States that rely on HealthCare.gov have faced challenges in the transfer of information in a timely and efficient way. This is because, in most states, HealthCare.gov only assesses Medicaid eligibility, leaving it up to the state to make the final eligibility determination. This process adds an extra administrative layer that costs the states money and can lead to unnecessary delays in coverage enrollment. Moreover, states using HealthCare.gov must still electronically transfer information between Medicaid and HealthCare.gov after eligibility has been determined, and 20 states report that these transfers are delayed or problematic. Given these FFM-related operational concerns, it makes more sense to continue to develop a system where these processes are interconnected and functioning in a way that ensures the efficient eligibility determination and enrollment of Minnesotans. -

Moving to an FFM would cost Minnesota $5 million and distract from improving the interconnectedness of Minnesota’s IT eligibility and enrollment system.

The estimated cost for Minnesota to move to the FFM platform is $5 million. Not only would this move take additional state resources, but it would divert attention away from the slow but steady improvements in Minnesota’s IT infrastructure that are needed to integrate state and county programs. The time and money that could have been spent on the build-out of Minnesota’s IT system would be tied up with making Minnesota’s systems interface with a new federal system that is still a work in progress. - An SBM gives Minnesota control of the funding and function of our health insurance Navigators, who have played a critical role in local enrollment efforts.

Navigators and enrollment assisters have been critical in enrolling people in MNsure, MinnesotaCare, and Medicaid. Without an SBM, the navigator function becomes a component of the FFM and is thereby removed from state and local control. The Task Force recognizes and acknowledges the importance of community-level enrollment assistance functions, going so far as to recommend additional improvements to consumer assistance resources. Minnesota has a strong history of efficiently-run and successful enrollment programs, and our Navigator program under the ACA is no exception.

- With an SBM, Minnesota maintains access to state-level data that support health system planning and evaluation.

Minnesota currently has ready access to eligibility and enrollment data, a benefit that is not available to states using the HealthCare.gov platform. Access to granular data enhances Minnesota’s ability to understand its health insurance markets, evaluate and project the movement of people between coverage types, and design and target effective outreach strategies. Without easily accessible eligibility and enrollment data, we cannot refine and improve broad access to coverage.

The bottom line is that there is no silver bullet for marketplace implementation. State-Based Marketplaces and Federally-Facilitated Marketplaces each have their own challenges with the accommodation of complex eligibility rules and enrollment processes that are part of the ACA. However, Minnesota has a history of successful health coverage expansion, enrollment expertise, and operational efficiency that warrants keeping the marketplace within our sphere of control. We are a unique state that may not be appropriately represented at the federal level through an FFM, and we can more effectively assert our own interests by taking charge of them ourselves.

Publication

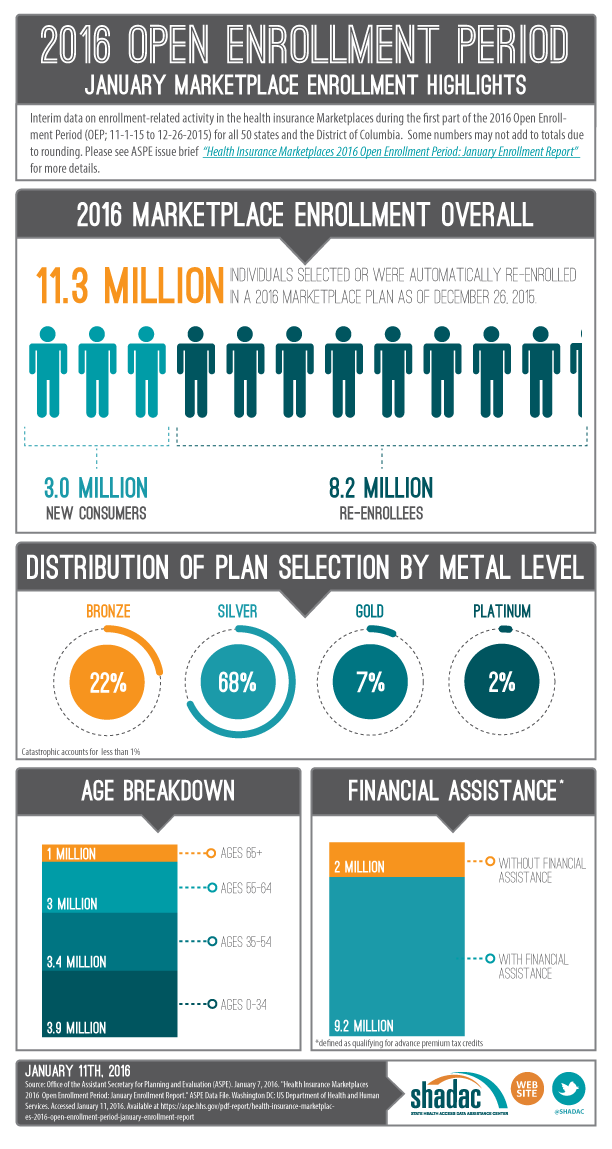

INFOGRAPHIC - 2016 OEP: January Marketplace Enrollment Highlights

The office of the Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) realeased national and state-level enrollment-related information for the first two months of the Health Insurance Marketplace 2016 open enrollment period (11-1-15 to 12-26-15).

Download here: ASPE 2016 OEP January Marketplace Enrollment Highlights

Blog & News

Ann DePriest: Coverage and Access Disparities Between Whites and Latinos Persist (Cross-Post)

July 12, 2016:The following content is cross posted from California Healthcare Foundation. It was first published December 1, 2015.

While Latinos in California have experienced important improvements in access to health insurance and care under the Affordable Care Act, they continue to lag behind Whites in important measures.

The data tracked on CHCF's ACA 411 will tell the story of how health care reform is changing coverage, access, and affordability in California.

The results of the 2014 California Health Insurance Survey (CHIS) show that Hispanics/Latinos in California continue to experience disparities in insurance coverage and access to care, especially compared to Whites.

Between 2013 and 2014, the uninsured rate among Latinos remained relatively stable — 21.4% in 2013 versus 20.1% in 2014. However, Latinos reported being uninsured at nearly three times the rate of Whites in 2014 (20.1% vs. 7.6%), whereas in 2013, the Latino uninsured rate was only double that of Whites (21.4% vs. 10.3%).

Long-term uninsurance rates, defined as being uninsured for a year or more, tell a similar story. Between 2013 and 2014, Latinos were uninsured long-term at similar rates — 16.4% in 2014 versus 18% in 2013. Both of these rates are more than double the rates reported by Whites in these years, 6.3% and 7.8%, respectively.

The reasons for being uninsured reported by Latinos and Whites differ greatly. Latinos are five times more likely to report eligibility issues due to citizenship/immigration status or health conditions as the reason for lacking insurance (29.9% vs. 6.2%), a trend that increased significantly among Latinos between 2013 and 2014 — 20.1% in 2013 versus 29.9% the next year. There was, however, a significant decrease in Latinos reporting being uninsured due to cost (44.9% in 2013 vs. 37.3% in 2014). (Note: While the indicator used here includes both citizenship/immigration status and health conditions, starting in 2014, insurers were required to issue coverage to all applicants without regard to health status.) There was not a statistically significant decline in the share of Whites reporting cost as the primary reason for being uninsured, although the share of the overall statewide population reporting cost as the reason for remaining uninsured fell from 52.6% to 42.6%.

The results suggest that new access to Covered California subsidies and Medi-Cal are mitigating the extent to which affordability is a reason for remaining uninsured among Latinos and other communities of color and that citizenship/immigration status is increasingly identified as a barrier for uninsured Latinos.

Differences in the types of coverage among Whites and Latinos also persist. Latinos are nearly half as likely to report employment-based insurance (35% vs. 67%), and this coverage decreased significantly among Latinos between 2013 and 2014, from 39.7% to 34.6%. Latinos are also half as likely to report individual insurance as Whites (4.3% vs. 9.8%) but three times more likely to report coverage through Medi-Cal, Healthy Families, or CHIP (38.8% vs. 12.4%). However, the number of Latinos reporting individual coverage did increase significantly in 2014, up from 2.8% in 2013. That is likely due to the availability of more affordable coverage options through Covered California. (Individual coverage among Whites was statistically unchanged between 2013 [9.8%] and 2014 [10%]).

Given the disparity between Latinos and Whites in insurance rates and sources of coverage, it is not surprising that among those with a usual source of care, more Latinos reported seeking care from a community clinic, government clinic, or community hospital (34.8% vs. 14.5%), while more Whites than Latinos reported seeking care from a doctor's office, HMO, or Kaiser Permanente (72.2% vs. 43.4%).