Blog & News

Pandemic-Era Trends in Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance (ESI), 2019-2020

July 7, 2022:The COVID-19 pandemic continues to disrupt many patterns of life and work in the United States and internationally, while exacerbating many long-standing concerns regarding health care affordability, access, and utilization as well as rates of health insurance coverage for Americans. In this regard, one area of potential pandemic-related impact to consider is coverage rates for employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI), which remains the largest source of coverage for Americans, with 60.1 million private-sector employees enrolled in ESI in 2020.1

In anticipation of the release of the 2021 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component (MEPS-IC) data, SHADAC researchers analyzed private-sector ESI estimates from the 2020 MEPS-IC to better contextualize the forthcoming 2021 estimates. Understanding 2020 coverage data will supply a pandemic-era baseline, while providing a critical vantage point from which to observe and interpret trends in ESI composition, affordability, and access in this critical market.

This narrative provides an overview of the 2020 MEPS-IC private-sector ESI estimates, covering firm size, ESI cost, and access. It’s important to note that the overlay of COVID-19 on this data makes it difficult to interpret the cause of certain changes when compared to pre-pandemic estimates. One area where this is evident is within the composition of private-sector employees by employer firm size.

Small firms declined significantly in 2020

Many employers offer ESI to their employees, regardless of the number of individuals they employ. However, while ESI remains the most common source of coverage for Americans, the composition of private sector employees enrolled in ESI shifted significantly from 2019 to 2020. Specifically, the number of employees in small firms (defined here as <50 employees) experienced a 19 percent decline over this timeframe, leaving a greater proportion of medium and large firms (defined here as >50 employees) to drive trends in ESI access to coverage and cost.

With larger firms comprising an increasingly significant portion of the private sector, trends among this subset of firms are driving overall changes between 2020 and 2019. For this reason, it is difficult to analyze changes in ESI estimates from 2020 to 2019, as these changes could be attributed to actual trends in access, cost, and affordability, or they could be directly tied to this shift in composition of employers and employees.

Number of private-sector employees in the United States, by firm size: 2019—2020

| Employees, all firms |

Less than 50 employees |

50 or more employees |

|

| 2019 | 131,333,000 | 35,113,000 | 96,220,000 |

| 2020 | 122,677,000 | 28,507,000 | 94,171,000 |

| 2019-2020 Change | -8,656,000 | -6,606,000 | -2,049,000 |

| 2019-2020 Percent Change | -7% | -19% | -2% |

Source: SHADAC analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey—Insurance Component, 2019, 2020.

ESI costs and premiums remain mostly stable

Monitoring costs associated with ESI is essential for understanding health care-related financial burdens for employees. Nationally, 2020 premiums and cost sharing remained relatively stable for employees enrolled in ESI. While premiums for single coverage increased slightly by 2.5 percent ($177), family premiums, employee contributions, and deductibles (for both single and family coverage) remained steady when compared to 2019.

When examined on a state-level, 2020 ESI costs are more varied. Nationally, the average premium for single coverage was $7,149. Certain states exceeded that average in 2020, with Alaska and New York monthly premiums surpassing $8,000 ($8,635 and $8,177 respectively). Meanwhile, Alabama had the lowest premium for single coverage at $6,393. There was also a great deal of variation across states in the size of deductibles. Nationally, the average deducible for single coverage was just under $2,000 in 2020. However, deductibles ranged from an average of $2,500 in Montana to less than $1,500 in Hawaii.

High-deductible health plans (HDHP) represent one common form of ESI. Nationwide, the percent of employees enrolled in a HDHP increased in 2020, rising from 50.5 to 52.9 percent. Moreover, the majority of private-sector employees were enrolled in a HDHP across 36 states in 2020. North Carolina had the highest percentage of HDHP-enrolled employees at 69.5 percent, and Hawaii was at the other end of the spectrum with only 17.6 percent of employees enrolled in HDHPs.

Access to coverage varies by state

Employee access to ESI has three components:

Employee Offer: An employee must work in an establishment that offers coverage.

Employee Eligibility: An employee must meet the criteria established by the employer to be eligible for coverage that is offered.

Employee Take-Up: The employee must decide to enroll in (“take up”) the offer of ESI coverage.

The decision to offer ESI to employees is determined by the employer, with 51.1 percent of private sector firms choosing to offer coverage in 2020 (compared to 47.4 percent in 2019). However, although over half of employers provided optional ESI, not all of their employees were eligible to enroll in that coverage. Meaning, while 86.9 percent of employees worked for an employer offering ESI coverage in 2020, only 80.5 percent were eligible for that coverage; eligibility could be based on a minimum number of hours worked per pay period or a minimum length of service with an employer, for example. Among employees eligible for ESI, overall enrollment declined in 2020, dropping from 71.9 percent to 70.8 percent—a difference of 1.745 million employees.

ESI access also varied across states in 2020. In Hawaii, Tennessee, Massachusetts, Illinois, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the District of Columbia (D.C.), more than 90 percent of employees worked at a firm that offered ESI. Meanwhile, less than 75 percent of Montana and Wyoming employees worked for an employer that offered ESI (73.8 percent and 70.6 percent, respectively).

It’s important to note that trends in access are particularly difficult to interpret due to the sharp decline in employees who work in firms with <50 employees, as small firms are much less likely to offer coverage.

To revisit 2019 ESI findings from SHADAC, see the following products:

- Printable version of 2019 ESI Report Narrative

- Companion Blog and Infographic highlighting key findings at the national level regarding ESI coverage affordability and access

- Two-Page Profiles on ESI trends for each state

- 50-State Interactive Map showing levels of, and changes in, average annual premiums for single and family coverage in 2019, with links to state profile pages

- 50-State Comparison Tables including 2015-2019 ESI data

Notes and Sources

Hawaii has a broad employer mandate that preceded the ACA. The Hawaii Prepaid Health Care Act, enacted in 1974, requires private employers to provide health insurance for employees who work at least 20 hours (some exceptions apply).

High-deductible health plans (HDHP) are defined as plans that meet the minimum deductible amount required for Health Savings Account (HSA) eligibility (e.g., $1,400 for an individual and $2,800 for a family in 2020).

The labor market changed significantly between 2019 and 2020 with a dramatic reduction in small firm employment. It is difficult to determine whether 2020 changes in ESI were driven by this change in the labor force or reflect actual changes in ESI access and cost.

Data are from the 2019–2020 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey–Insurance Component (MEPS-IC), produced by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and are available on SHADAC’s State Health Compare web tool at statehealthcompare.shadac.org.

1 State Health Access Data Assistance Center. (n.d.). Health Insurance Coverage Type (2020)* http://statehealthcompare.shadac.org/bar/279/health-insurance-coverage-type-2020-by-total#0/1/5,4,1,10,86,9,8,6/32/325

Blog & News

State and Federal Relief Prevented Deep Backslide in Health Care Affordability in California in 2020 (CHCF Cross Post)

May 18, 2022:The following content is cross-posted from California Health Care Foundation. It was first published on May 18, 2022.

Author: Colin Planalp, Research Fellow, SHADAC

In 2020, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic meant the imposition of incredible burdens on every corner of US society, particularly the health care system and the people it serves. There were well-founded fears that the pandemic, and the concurrent economic crisis, could make health insurance and health care unaffordable for even more people — already a long-standing problem in California.

In response to the pandemic, the US government enacted historic relief programs, including multiple instances of direct cash payments to a majority of US families. Those federal policies coincided with California health insurance reforms that, while developed before the pandemic, were implemented in 2020.

This analysis of the California Health Insurance Survey (CHIS) shows that Californians were largely protected from experiencing a major erosion in their ability to pay for health insurance and care. Despite this overall positive finding, the 2020 CHIS data on health care affordability continued to demonstrate clear inequities by income and race/ethnicity.

Key Findings

California’s uninsured rate declines, yet cost remains top reason for lacking health insurance. The rate of Californians under 65 without health insurance reached a historic low of 7.0% in 2020. However, 51.9% of uninsured people said they lacked coverage because it was too expensive.

Rate of going without needed care due to cost dropped in 2020. Among the 8.6% of Californians who reported forgoing needed medical care in 2020, 32.0% said it was concerns about the cost that caused them to go without care. That rate was significantly lower than the rate of 43.6% in 2019.

Fewer Californians reported difficulty paying medical bills. From 2019 to 2020, the rate of Californians reporting that they’ve had trouble paying medical bills in the past year declined significantly, from 13.3% to 11.1%. However, when breaking out the data by income, only those with higher incomes saw statistically significant improvement. Californians with lower incomes — 200% to 299% of federal poverty guidelines (FPG), 100% to 199% FPG, and below 100% FPG — reported no significant changes.

Less trouble affording necessities due to medical bills in 2020. In 2020, the rate of Californians who reported having trouble paying for basic necessities (such as food or clothing) because of medical bills declined significantly to 31.0% from 39.8% in 2019. Rates of trouble paying for necessities due to medical bills also declined across most income levels.

Practice of using credit card debt to finance medical bills declined. In 2020, the rate of Californians who reported taking on credit card debt to finance medical bills declined significantly, from 56.5% in 2019 to 44.3%. That finding held consistent for Californians across income levels — except for those with the lowest incomes.

Racial and ethnic disparities persisted in 2020. Although California experienced significant improvements in some measures of health care and insurance affordability in 2020, certain long-standing inequities persisted. For example, Black people reported the highest rate of trouble paying medical bills in 2020, at 14.0%, followed closely by Latinos/x, at 12.7%. Asians, Black people, and Latinos/x also reported similarly high rates of trouble paying for necessities due to medical bills (39.4%, 36.2%, and 33.1%, respectively).

Together, these findings provide some encouraging news. In a year of massive economic upheaval that would typically have caused serious financial problems for many Californians, they instead reported improvements in health care and insurance affordability. However, improvements were likely due, at least in part, to federal programs that were mostly designed to be temporary. Some have already expired. Additionally, the historically high inflation of 2021 and 2022 have since strained people’s finances.

But the fact that California experienced such measurable improvements in health insurance and health care affordability during a broad and deep recession shows that those problems don’t have to be intractable. In the future, it will be key to monitor these measures as policymakers in California and at the federal level consider initiatives to protect people against unaffordable health care and insurance costs, which remain a long-term challenge.

Blog & News

Covid-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the U.S. has Reached a Plateau: Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey

April 1, 2022:Previous analysis produced by SHADAC using data from the Household Pulse Survey (HPS) showed promising evidence of a reduction in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy during the first three months of 2021. However, though this report highlighted an overall decline in hesitancy, it also showed disparities in the level of hesitancy between demographic and socioeconomic groups. In an effort to continually illuminate barriers to vaccine receipt, this blog provides an updated look at vaccine hesitancy among U.S. adults (age 18 and older) using HPS data from January through October 2021.

|

The Household Pulse Survey is an ongoing weekly tracking survey designed to measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. These data provide multiple snapshots of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and are the only data source to do so at the state level over time. Click on any graphic throughout this blog to view it in full-screen mode. |

The HPS allows respondents to identify multiple reasons for not receiving all vaccine doses.

For the survey period of January 6-July 5 the reasons listed on the survey form included:

| 1) Concerned about possible side effects 2) Plan to wait and see if it is safe and may get it later 3) Think other people need it more than I do right now 4) Don't know if a vaccine will work |

5) Don't trust the vaccine

6) Don't trust the government

7) Don't believe I need a vaccine

8) Don't like vaccines

|

9) Concerned about the cost of a COVID-19 vaccine 10) My doctor has not recommended it 11) Other reason |

For the survey period of July -October 11 the reasons listed on the survey form changed to include:

| 1) Concerned about possible side effects 2) Plan to wait and see if it is safe and may get it later 3) Don't know if a vaccine will protect me 4) Don't trust the vaccine |

5) Don't trust the government

6) Don't believe I need a vaccine

7) Don't think COVID-19 is that big of a threat

8) My doctor has not recommended it

|

9) Concerned about the cost of a COVID-19 vaccine 10) Hard for me to get a vaccine 11) Experienced side effects from 1st dose of vaccine 12) Believe one dose is enough to protect me |

Because the reasons for not receiving a vaccine changed between these two periods, they will be reported separately in our analysis.i

Share of adults who received or plan to receive all COVID-19 vaccine doses plateaued at the end of 2021.

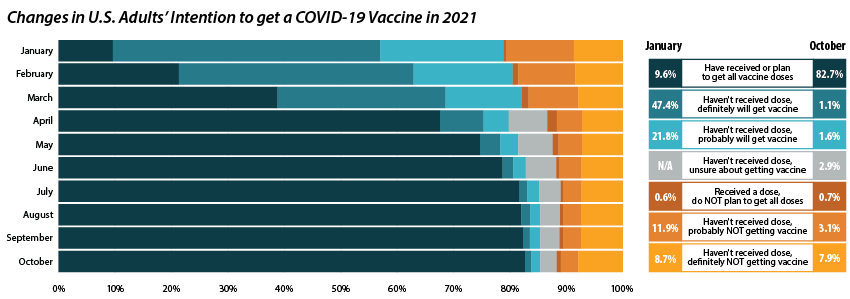

From July through October 2021, the percent of people who have received or plan to receive all COVID-19 doses plateaued at around 80.0 percent.ii,iii This was after an initial jump from 9.6 percent in January to 67.6 percent in April. The initial increase drew mainly from the “Definitely planning to receive a vaccine” and “Probably going to receive a vaccine” groups. The percent of people who “Received a dose, but do not plan to receive all doses,” “Haven’t received a dose and are unsure about getting a vaccine,” “Haven’t received a dose and are probably not getting a vaccine,” and “Haven’t received a dose and definitely are not getting a vaccine” has also remained stable over the same period. Collectively, these four groups, which we define as being “hesitant,” dropped from a rate of 21.1 percent in January to 14.8 percent in July, where it’s remained since.

Vaccine Hesitancy varied by state, but nearly all states saw a reduction.

Nationally, 14.6 percent of adults reported being hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine in October 2021. This varied across states, from a high of 28.9 percent in Wyoming to a low of 5.4 percent in the District of Columbia (D.C.).

The national rate of adult vaccine hesitancy decreased from 14.8 percent in July to 14.6 percent in October—a 0.2 percentage-point (PP) decrease. This overall decrease, though not significantly large, was reflected in 26 states plus D.C., which also saw promising reductions in vaccine hesitancy. Twenty-four states did not show reductions in hesitancy over that time period.

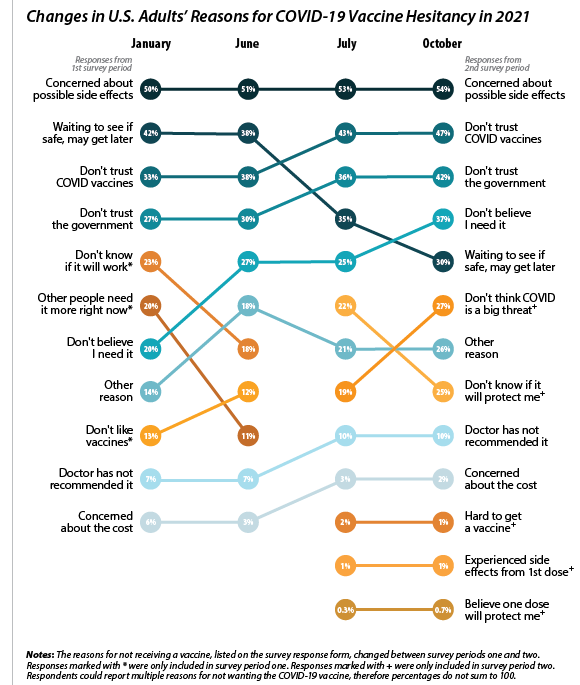

Concerns over possible side effects remains the top reason reported for vaccine hesitancy.

Of the 21.1 percent of people who reported hesitancy in January, nearly half (48.3 percent) cited “Concerns over possible side effects” as a reason.iv This continued to be the most reported reason for hesitancy, with 53.8 percent who were hesitant in October citing it as a reason. The percent of people reporting “Plan to wait and see if it is safe” declined over the 10-month period, from 42.1 percent in January to 30.4 percent in October, and dropped from the second to the fourth most reported reason behind “Don’t trust COVID-19 vaccine” and “Don’t trust the government.” This shift in reasoning behind vaccine hesitancy highlights a major barrier to vaccination goals, as establishing trust is a potentially more difficult and imprecise process than quelling fears of side effects.

Of the 21.1 percent of people who reported hesitancy in January, nearly half (48.3 percent) cited “Concerns over possible side effects” as a reason.iv This continued to be the most reported reason for hesitancy, with 53.8 percent who were hesitant in October citing it as a reason. The percent of people reporting “Plan to wait and see if it is safe” declined over the 10-month period, from 42.1 percent in January to 30.4 percent in October, and dropped from the second to the fourth most reported reason behind “Don’t trust COVID-19 vaccine” and “Don’t trust the government.” This shift in reasoning behind vaccine hesitancy highlights a major barrier to vaccination goals, as establishing trust is a potentially more difficult and imprecise process than quelling fears of side effects.

When examining survey responses from January and October 2021, our analysis found that both the number of reasons for hesitancy (2.5 per person and 2.9 per person, respectively) and the most common reason for hesitancy (“concerns over possible side effects”) remained statistically unchanged between the two survey periods. Our analysis also found that the rankings of the reasons for hesitancy held within subpopulations by region, race/ethnicity, and income, as highlighted in the following sections.

Disparities in vaccine hesitancy improved over time, though many remain.

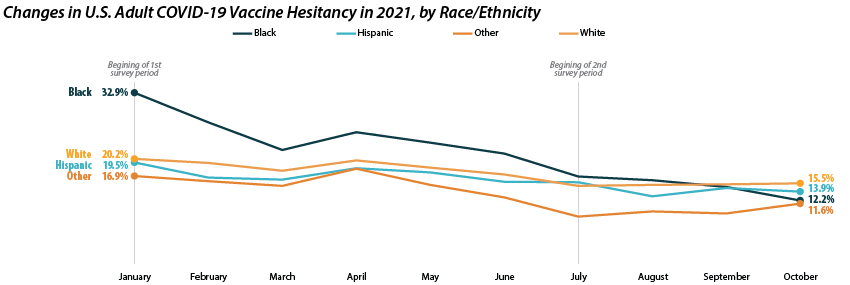

As with our previous analysis of the HPS, both overall hesitancy and disparities in vaccine hesitancy between demographic and socioeconomic groups has improved, though unevenly. The most notable reduction comes among Black adults, who registered a high of 32.9 percent in January and dropped down to 12.2 percent in October. This decline in vaccine hesitancy essentially closed the gap between Black adults and other racial/ethnical groups. Unfortunately, the rate of decline seems to have reached a plateau among certain demographics. For example, among White adults the hesitancy rate stabilized at around 15.0 percent between July and October.

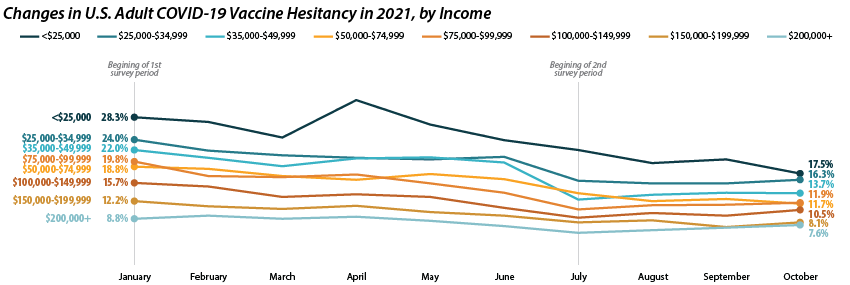

Similar patterns appear when looking within and across income level. Those making less than $25,000 reported the highest level of hesitancy in January at 28.3 percent, but have shown a marked reduction down to 17.5 percent in October. This has significantly closed the gap in hesitancy between this group and those at higher income levels. However, once again, changes within subgroups appear to have reached a stable level of hesitancy. Among those making $50,000-$74,999 this appears to be around 12.0 percent, while for those making $150,000 or more, this appears to be around 7.0 percent.

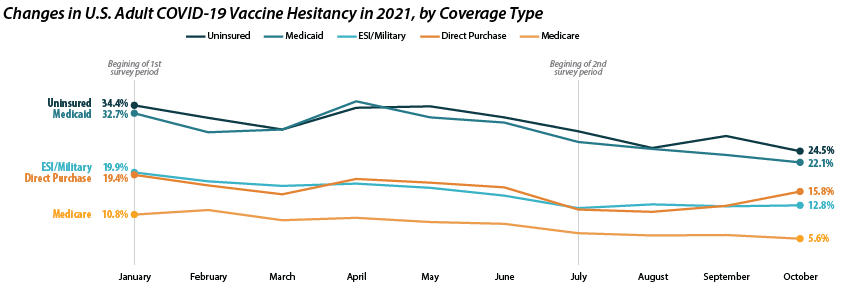

Patterns of reduced vaccine hesitancy followed by rate leveling continued to be true among groups with fewer connections to the health care system, as proxied by insurance status. Hesitancy rates have fallen generally across all insurance statuses; however, the uninsured and those with Medicaid coverage continue to have the highest rates of hesitancy, at 24.5 percent and 22.1 percent in October as compared to those with ESI/Military, Direct Purchase, or Medicare coverage.

Note: All changes and differences in this post are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level unless otherwise noted.

Related Reading

SHADAC Blog: Vaccine Hesitancy Decreased During the First Three Months of the Year: New Evidence from the Household Pulse Survey

SHADAC Blog Series: Measuring Coronavirus Impacts with the Census Bureau's New Household Pulse Survey: Utilizing the Data and Understanding the Methodology

i U.S. Census Bureau. (2021, November 3). 2021 Household Pulse Survey User Notes [Phase 3.2]. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/Phase3-2_2021_Household_Pulse_Survey_User_Notes_11032021.pdf

ii This only includes primary series doses and excludes booster doses.

iii This percentage is higher than administratively reported COVID-19 vaccine receipt. The differences are due to both the inclusion of those who “Plan to receive all vaccine doses” and the known discrepancies between administrative and survey data.

iv The HPS allows those who are “Probably going to receive a vaccine” to report reasons for hesitancy; however, this group is not included in our definition of “hesitant.”

Blog & News

Expert Perspective and Issue Brief: Tracking the Data on Medicaid’s Continuous Coverage Unwinding (State Health & Value Strategies Cross-Post)

January 21, 2022:The following content is cross-posted from State Health and Value Strategies published on January 21, 2022.

Authors: Emily Zylla, Elizabeth Lukanen, and Lindsey Theis, SHADAC

Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP) programs have played a key role in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a vital source of health coverage for millions of people. However, when the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) Medicaid “continuous coverage” requirement is discontinued states will restart eligibility redeterminations, and millions of Medicaid enrollees will be at risk of losing their coveragei.

A lack of publicly available data on Medicaid enrollment, renewal, and disenrollment makes it difficult to understand exactly who is losing Medicaid coverage and for what reasons. Publishing timely data in an easy-to-digest, visually appealing way would help improve the transparency, accountability, and equity of the Medicaid program. It would inform key stakeholders, including state staff, policymakers, and advocates, allowing them to more fully understand the impacts of Medicaid policy changes on enrollees’ access, and give them an opportunity to modify or implement intervention strategies as needed. States already collect a significant amount of data that could inform their success in enrolling and retaining eligible individuals in Medicaid. Many advocates and researchers have been calling for increased transparency around this data in order to better understand the barriers and challenges individuals face when trying to enroll in or maintain coverage.

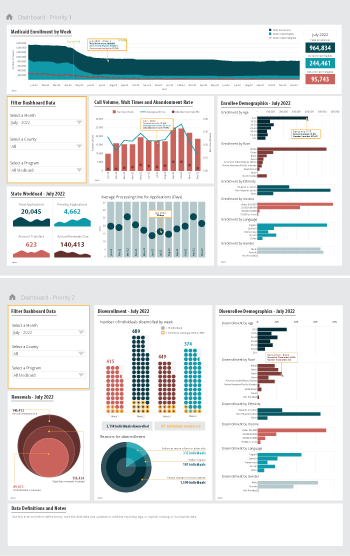

One effective way to monitor this dynamic issue is by creating and publishing a Medicaid enrollment and retention dashboard. A typical data dashboard is designed to organize complex data in an easy-to-digest visual format, thus allowing the audience to easily interpret key trends and patterns at a glance. A new issue brief examines the current status of Medicaid enrollment and retention data collection, summarizes potential forthcoming reporting requirements, and describes some of the best practices when developing a data dashboard to display this type of information.

The issue brief lays out a phased set of priority measures and provides a model enrollment and retention dashboard template that states can use to monitor both the short-term impacts of phasing out public health emergency (PHE) protections and continuous coverage requirements, as well as longer-term enrollment and retention trends.

State Medicaid Enrollment and Retention Dashboard – Measurement Priorities

Priority 1 – Use currently reported data: Start with the data that are already collected and submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under the 11 Medicaid performance topics.

Priority 1 – Use currently reported data: Start with the data that are already collected and submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under the 11 Medicaid performance topics.

Priority 2 – Track reasons for disenrollment: Include measures in the proposed Build Back Better Act (BBB) legislative language that address the reasons why people are being disenrolled.

Priority 3 – Monitor coverage transitions: Add measures to address issues of transitions between programs and churn—the moving in and out of coverage—that frequently occurs in Medicaid and CHIP.

Priority 4 – Explore reasons for and consequences of disenrollment: Field disenrollment surveys that could provide quantitative and qualitative data that could be used to understand both the enrollee’s experience navigating Medicaid processes as well as the consequences of disenrollment.

Regardless of the measures highlighted, an overarching goal of any Medicaid enrollment and retention dashboard should be a focus on displaying disaggregated data. Providing data broken down by various population characteristics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, income, gender, language, or program type) or geographic areas (urban, rural) will make it easier to understand the potentially disproportionate impact of administrative enrollment and renewal policies on communities of color, persons with lower incomes, and other populations that face disparities. Access to this type of granular data provides stakeholders an opportunity to take action in order to minimize needless loss of coverage.

Designing an easy-to-understand dashboard that is accessible to all interested stakeholders—state or county program staff, navigators or enrollment assisters, and advocates—will highlight the early warning signs of large numbers of people losing Medicaid coverage. States should start small, using data dashboard best practices and as they gain experience publicly reporting this data, consider adding additional measures over time.

i Buettgens, M. & Green, A. (September 2021). What Will Happen to Unprecedented High Medicaid Enrollment after the Public Health Emergency? [Research report]. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104785/what-will-happen-to-unprecedented-high-medicaid-enrollment-after-the-public-health-emergency_0.pd

Publication

COVID-19 illness personally affected nearly 97 million U.S. adults

New brief shows results from SHADAC COVID-19 Survey on population experiences with COVID sickness and death

Researchers at SHADAC have fielded an updated version of the SHADAC COVID-19 Survey in April 2021, aimed at understanding respondents’ experiences with illness and death due to COVID-19 for themselves, their families, and their contacts.

Results from the survey, presented in the brief to the right, showed that almost 40% of adults in the U.S.:

- Know someone who has died from COVID.

Among the adults surveyed, 37.7 percent responded that they know someone who died from the coronavirus. By race/ethnicity, roughly half of Black (56.9 percent) and Hispanic (48.2 percent) adults reported knowing someone who died of COVID-19, a significantly higher amount than White adults or those who reported as “any other” or multiple races. Other breakdowns for this question included age, income level, and education level, for which adults reported similar rates to the overall total (37.7 percent), for knowing someone who died from the coronavirus.

- Either themselves have, or had a family member who has, contracted COVID.

Among the adults surveyed, 37.6 percent responded that either they or a family member had become ill due to COVID. Notable breakdowns included about half of Hispanic adults (51.5 percent) who reported that they or an immediate family member had COVID-19, and adults with some college or associate’s degree (44.0 percent) were also more likely to report that they or an immediate family member had COVID-19. Among other categories of age and income level, significantly different percentages from the overall total (37.6 percent) were not seen.

More on the survey

The SHADAC COVID-19 Survey on the impacts of the pandemic on respondents’ experiences with COVID-related illness and death was conducted as part of the AmeriSpeak Omnibus Survey conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago. The survey was conducted using a mix of phone and online modes in April 2021 among a nationally representative sample of 1,007 respondents age 18 and older.

This survey is a continuation of the initial SHADAC COVID-19 Survey, which was aimed at understanding the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on health care access and insurance coverage and pandemic-related stress, and was conducted as part of the same survey, by the same agency, during a similar time frame (April 24-26, 2020), using the same methods, and a similar population sample.

Results from the first iteration of the survey are available in separate briefs on health insurance coverage and access to care and pandemic-related stress, as well as in a pair of chartbooks.