Blog & News

90 percent of U.S. adults report increased stress due to pandemic

May 26, 2020:Colin Planalp, MPA, Giovann Alarcon, MPP, Lynn A. Blewett, PhD,

The coronavirus pandemic and ensuing economic crisis have introduced a new and unique set of conditions that trigger stress in the United States population. Many individuals are concerned about contracting the virus and developing COVID-19 symptoms, worried about job loss, and experiencing other strains caused by stay-at-home orders. The SHADAC COVID-19 Survey, conducted between April 24 and 26, 2020, by NORC at the University of Chicago, asked a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults how they were coping with the stress caused by the pandemic. This brief highlights key results from the survey, relating to stress and coping mechanisms for a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults (age 18 and older). More information on the SHADAC COVID-19 Survey findings regarding worries about COVID-19 costs are available here.

Elevated stress was reported consistently across demographic groups

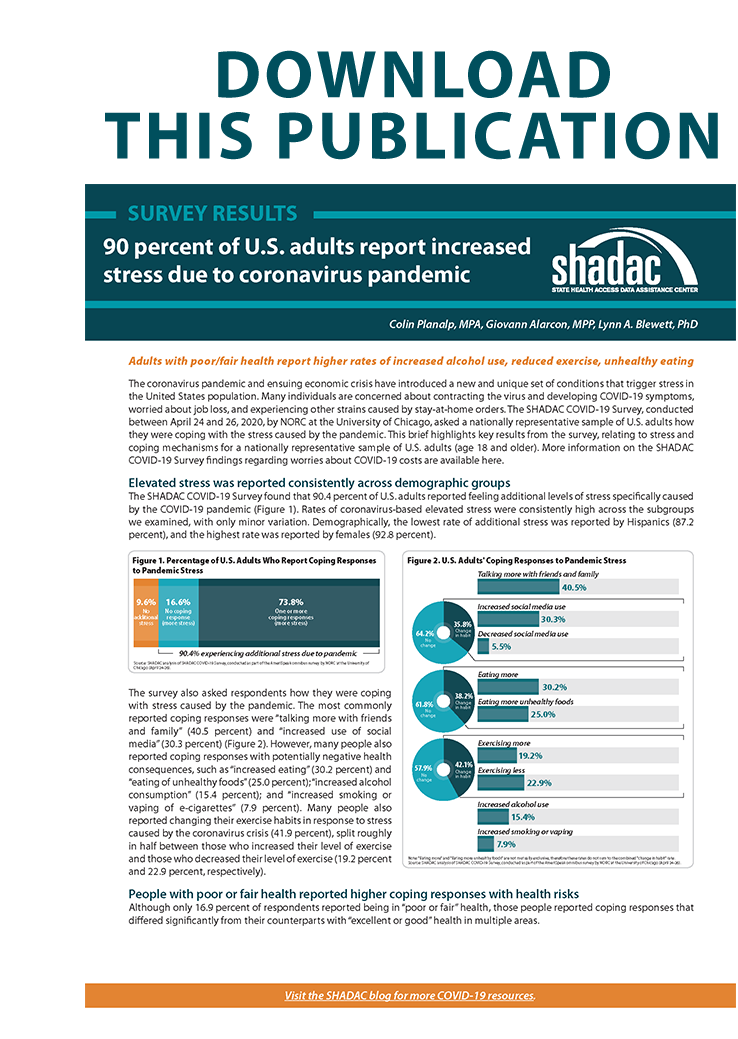

The SHADAC COVID-19 Survey found that 90.4 percent of U.S. adults reported feeling additional levels of stress specifically caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1). Rates of coronavirus-based elevated stress were consistently high across the subgroups we examined, with only minor variation. Demographically, the lowest rate of additional stress was reported by Hispanics (87.2 percent), and the highest rate was reported by females (92.8 percent).

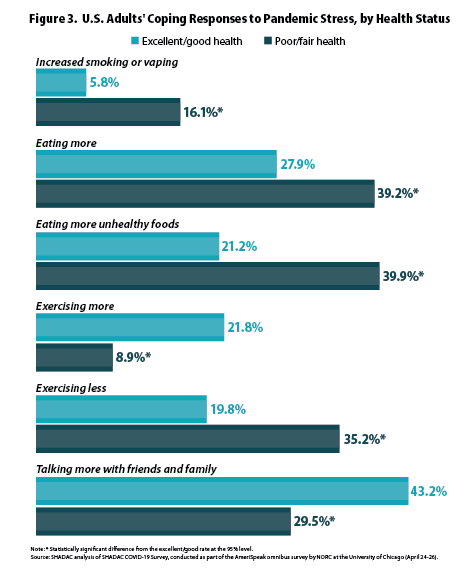

The survey also asked respondents how they were coping with stress caused by the pandemic. The most commonly reported coping responses were “talking more with friends and family” (40.5 percent) and “increased use of social media” (30.3 percent) (Figure 2). However, many people also reported coping responses with potentially negative health consequences, such as “increased eating” (30.2 percent) and “eating of unhealthy foods” (25.0 percent); “increased alcohol consumption” (15.4 percent); and “increased smoking or vaping of e-cigarettes” (7.9 percent). Many people also reported changing their exercise habits in response to stress caused by the coronavirus crisis (41.9 percent), split roughly in half between those who increased their level of exercise and those who decreased their level of exercise (19.2 percent and 22.9 percent, respectively).

The survey also asked respondents how they were coping with stress caused by the pandemic. The most commonly reported coping responses were “talking more with friends and family” (40.5 percent) and “increased use of social media” (30.3 percent) (Figure 2). However, many people also reported coping responses with potentially negative health consequences, such as “increased eating” (30.2 percent) and “eating of unhealthy foods” (25.0 percent); “increased alcohol consumption” (15.4 percent); and “increased smoking or vaping of e-cigarettes” (7.9 percent). Many people also reported changing their exercise habits in response to stress caused by the coronavirus crisis (41.9 percent), split roughly in half between those who increased their level of exercise and those who decreased their level of exercise (19.2 percent and 22.9 percent, respectively).

People with poor or fair health reported higher coping responses with health risks

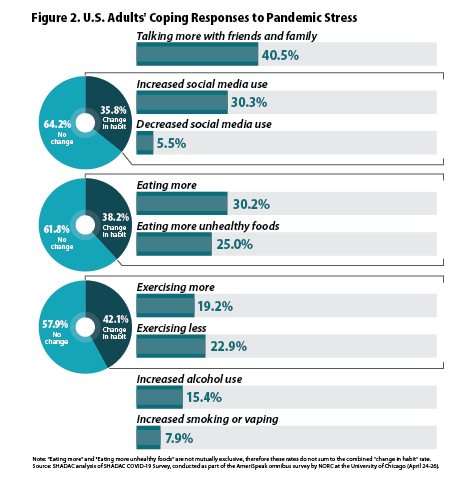

Although only 16.9 percent of respondents reported being in “poor or fair” health, those people reported coping responses that differed significantly from their counterparts with “excellent or good” health in multiple areas.

Increased smoking or vaping

People with poor/fair health reported increased smoking or vaping at rates almost triple those of people with excellent/good health (16.1 percent vs. 5.8 percent), which was a statistically significant difference (Figure 3).

Eating more and eating unhealthy foods

People with poor/fair health reported increased consumption of unhealthy foods at almost double the rate of people with excellent/good health (39.9 percent vs. 21.2 percent), while also reporting higher rates of increased eating (39.2 percent vs. 27.9 percent)—both of which were statistically significant differences.

Less exercise

People with poor/fair health also were more likely to report reduced exercise in response to pandemic stress than people with excellent/good health (35.2 percent vs. 19.8 percent), and they were correspondingly less likely to report exercising more in response to pandemic stress (8.9 percent vs. 21.8 percent). Both of these differences in rates of exercise were statistically significant.

Social connections

As with the other indicators listed in the SHADAC COVID-19 Survey, people with poor/fair health were significantly less likely to report talking more with friends and family to cope with stress than their counterparts with excellent/good health (29.5 percent vs. 43.2 percent).

Coping responses with health risks also found among other subpopulations

The SHADAC COVID-19 Survey also found that certain coping responses with greater potential health risks were more prevalent within other subpopulations:

Higher alcohol consumption by younger adults

Younger adults (age 18-29) were significantly more likely to report increased alcohol consumption than elderly adults (age 65 and older), who had the lowest rate (23.5 percent vs. 4.0 percent), as well as unhealthy changes in eating (eating more, eating more unhealthy foods) as compared with elderly adults, who again reported the lowest rate (48.2 percent vs. 27.1 percent). Younger adults were also significantly more likely to report increased social media use than elderly adults (41.2 percent vs. 23.8 percent).

Females reported higher unhealthy eating habits

Females were more likely to report changes in unhealthy eating (eating more, eating more unhealthy foods) than males (43.2 percent vs. 32.9 percent). Females also were significantly more likely than males to report talking more with friends or family (46.9 percent vs. 33.6 percent), and more likely to report increased social media use (36.5 percent vs. 23.8 percent).

Higher smoking and vaping by people with high school or less education

People with a high school education or less were significantly more likely to report increased smoking or vaping than people with a bachelor’s degree or more (11.9 percent vs. 5.3 percent). They also were less likely to report exercising more (12.5 percent vs. 27.6 percent).

People with higher incomes were more likely to report increased exercise

People with incomes of $100,000 or more were significantly more likely to report increased levels of exercising than those with incomes of less than $30,000 (30.1 percent vs. 11.9 percent). Conversely, people with incomes below $30,000 were significantly more likely to report greater unhealthy eating habits (eating more, eating more unhealthy foods) (44.2 percent vs. 31.6 percent).

Conclusion

Coping strategies are a natural response to increased stress levels due to concerns about the coronavirus pandemic. From the results of the SHADAC COVID-19 Survey, we found variation in coping responses by age, sex, education and income. However, some of the most distinctive differences in stress-coping responses were among people reporting poor or fair health, who reported higher rates of responses with potentially negative health impacts, such as increased alcohol consumption, reduced exercise and unhealthy eating habits. People with poor or fair health also reported lower rates of talking more with friends and family, raising concerns about greater social isolation for these people at a time when stay-at-home-orders have been official policies in many states.

It is critical that individuals are aware of their stress levels and the methods by which they are using to cope, and make sure that they take care of themselves and others. It is also critical to reach out to people with poorer health, who may need increased social supports during times of an economic and public health crisis. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the following activities as ways to deal with stress 1:

- Take breaks from the news.

- Take care of your body, including eating well-balanced healthy meals, exercise, get enough sleep, and avoid alcohol and drugs.

- Schedule time to unwind and do activities that you enjoy.

- Connect with others, including people you trust, family, and friends.

Moderating stress levels with healthy behaviors can contribute to an overall feeling of health and wellbeing that is important to cultivate during this time of an unprecedented pandemic.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, April 30). Stress and coping. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/cope-with-stress/index.html