The following Expert Perspective (EP) is cross-posted from State Health & Value Strategies.

Authors: Elizabeth Lukanen, Elliot Walsh, Robert Hest, SHADAC

Original posting date October 30, 2024. Find the original post here on the SHVS website.

Background on Census Data

Every fall, the U.S. Census Bureau releases detailed data on the population, including data on health insurance coverage. The American Community Survey (ACS) is the premier source for detailed state and substate data on income, poverty, disability, marital status, education, occupation, travel to work, disability, and health insurance coverage, among other topics. An important feature of the ACS is that it includes a large enough sample for estimates for all 50 states and the District of Columbia and, in most states, there is sample to explore data disaggregated by insurance coverage type, age, race/ethnicity, and more.

2023 Data Do Not Capture the Full Impact of Coverage Changes Related to Medicaid Unwinding

The new, full-year 2023 insurance estimates from the ACS reflect data collected from January 1, 2023 to December 31, 2023. This health insurance coverage data provide new national- and state-level insurance coverage estimates, but do not fully reflect the Medicaid unwinding.

According to administrative data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollment declined by 13.9 million between March 2023 and June 2024. Some of those who disenrolled likely transitioned to other coverage, and others may have become uninsured. However, coverage transitions that happened in 2024 are not captured in the 2023 estimates from the Census Bureau. Because of the large changes in Medicaid and CHIP coverage during the unwinding, compared to the current, on-the-ground reality in 2024, these 2023 coverage estimates likely overestimate rates of public coverage and potentially underestimate rates of uninsurance.

Despite this limitation, the data are still instructive about changes to coverage during the early months of the unwinding period and generally for the year 2023. This expert perspective looks at health insurance coverage estimates at the national and state levels, and examines children’s health insurance coverage, looking at children’s uninsurance rates by state and by income level. As more data are released SHADAC will conduct additional analyses, presenting coverage estimates across key demographic categories, including by race/ethnicity. Disaggregating data is critical to identifying inequities and gaps in coverage, informing policies to improve equity and to prevent new disparities. It is also vital for identifying state policies and practices effective in maintaining coverage for specific populations so that they might be adopted in other states.

Overall Uninsurance Rates Were Fairly Stable

The uninsurance rate in the U.S. remained unchanged from the previous year, sitting at 7.9% in 2023. This was mirrored by stability in uninsurance in the states. From 2022 to 2023, the uninsured rate fell in 11 states and increased in three states – Iowa, New Jersey, and New Mexico (these changes were statistically significant). Table 1 below highlights the states with the highest and lowest rates of uninsurance in 2023.

Table 1. States with the Highest and Lowest Rates of Uninsurance, 2023

| Highest Rates of Uninsurance | Lowest Rates of Uninsurance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Texas | 16.4% | Massachusetts | 2.6% |

Georgia and Oklahoma | 11.4% | District of Columbia | 2.7% |

Nevada | 10.8% | Hawaii | 3.2% |

Wyoming and Florida | 10.7% | Vermont | 3.4% |

Alaska | 10.4% | Minnesota | 4.2% |

Source: SHADAC analysis of U.S. Census Bureau 2022 and 2023 American Community Surveys. Click here for data from all states.

Children’s Uninsurance Rates Increased

Notably, while the overall uninsurance rate remained stable between 2022 and 2023, the rate for children went up slightly (rising from 5.1% in 2022 to 5.4% in 2023). This comes after two years of falling rates of uninsurance for kids.

Five states saw an increase in their uninsured rate for children (Alabama, Louisiana, New Mexico, South Carolina, and Texas). This wasn’t clearly driven by changes in private or public coverage, though, as both remained stable nationally and went up and down in a variety of states.

Texas is the only state where the data tell a clear story — there was a decline in public coverage for children (1.9 percentage point (PP) decrease to 36.8% in 2023) and an increase in uninsurance for children (1.0 PP increase to 11.9%).

Insurance Coverage Changes for Children (Birth Through Age 18), 2022 to 2023

Source: SHADAC analysis of U.S. Census Bureau 2022 and 2023 American Community Surveys.

Low-Income Children Saw Declines in Public Coverage

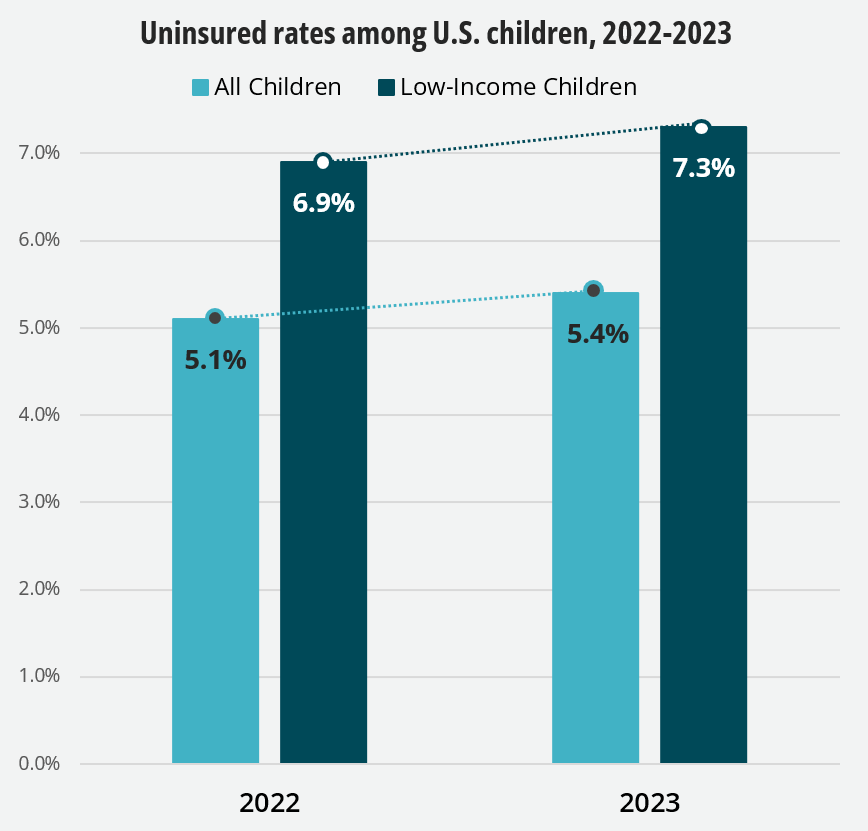

For U.S. children below 200% of the Census poverty threshold, uninsured rates rose by 0.4 PP to 7.3% in 2023 (see Figure 1 below). This significant increase was likely driven by a 0.6PP decrease in public coverage (bringing that national rate down to 72.6% in 2023) and a statistically unchanged rate of private coverage (27.0%).

Note: Low income children are defined as those below 200% of the Census poverty threshold. Source: SHADAC analysis of U.S. Census Bureau 2022 and 2023 American Community Surveys.

Among the states, Louisiana (+1.5PP), Michigan (+1.2PP), South Carolina (+1.6PP), and Texas (+1.5PP) all saw significant increases in uninsurance for low-income children, rising to 5.5%, 4.3%, 8.0%, and 15.4%, respectively. No states saw decreases in uninsurance rates for low-income children.

These increases in children without coverage are likely tied to declines in public coverage for low-income children. For example, Michigan saw a 3.1PP decrease in public coverage, bringing it down to 73.2%, and Texas saw a 2.5PP decrease in public coverage, bringing it down to 65.0%.

Health Equity Implications

Rising uninsurance rates for children, particularly for low-income children, has a number of implications for health equity. First, it is important to address the likely reason that uninsurance rates for low-income children rose. While the ACS data doesn’t collect information on the reasons for coverage transitions, the data suggests this was driven by declines in public coverage that correspond with the end of the Medicaid continuous coverage requirement (this is supported by administrative data showing that more than 4.5 million children lost Medicaid or CHIP between March 2023 and June 2024, a reduction of almost 11%).

Second, the essential role Medicaid plays in providing health insurance to low-income children, the majority of whom are racial and ethnic minorities, must be acknowledged. Over 60% of children enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP identify as African American or Black, Hispanic, Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, or multi-racial (State Health Compare, SHADAC, University of Minnesota, Accessed 10/10/2024). Declines in public coverage therefore disproportionately impact children of color. This is supported by early evidence that enrollees who identified as Hispanic or Black were twice as likely to report losing coverage because they could not complete the renewal process. SHVS will explore differences in coverage losses by race and ethnicity as more data are released.

Finally, Medicaid plays a critical role in children’s ability to access care – children with Medicaid or CHIP coverage report high rates of having a usual source of care and access to routine care. Further, evidence shows that they were as likely in the past 12 months to have seen a doctor, had a well child visit, and have had a dental exam as privately insured children. While having Medicaid does not erase the health inequity propagated by systemic racism it does improve access to important healthcare services and losing that coverage risks widening gaps in equity. As stated earlier, the full impact of the unwinding isn’t reflected in the latest data as it only includes the beginning months of the unwinding period. It will be important to revisit this once data from the entire unwinding period is released in order to get the full picture of coverage changes for this and other groups.